Welcome back to Martha’s Monthly, September Reads edition! My September reads were a mixed bag. There were a few books I thoroughly enjoyed and several that were just very average. I guess not every month can be a great reading month! September included a Booker Prize shortlist, a moving memoir, lots of translated fiction and one of the best thrillers I’ve ever read! So here are my September reads in their buy, borrow or bust glory.

‘Solito’ by Javier Zamora. ‘Soltio’ is the story of Javier’s migration from Central America into the United States in 1999. A 3,000 mile journey from his small town in El Salvador, through Guatemala and Mexico, and across the United States border. Javier is only nine when he undertakes this journey. Therefore, ‘Solito’ is a memoir of a child’s perspective of illegal immigration into the United States. Javier leaves his grandparents and extended family behind in El Salvador to reunite with his parents who live in the United States; a mother he hasn't seen in four years and a father he barely remembers. His parents pay for him to cross the border where he is travelling with complete strangers. The crossing is supposed to take two weeks, but it ends up taking seven, because a lot goes wrong.

‘For seven weeks (from April 20 1999, to June 10, 1999), no one knew where I was’

At only nine years of age, Javier cannot understand the true nature of this journey. He does not understand the peril he is consistently in for almost two months. Javier experiences boat crossings, trekking across the desert, having guns pointed at him, being arrested and held in a detention centre, all while being an unaccompanied minor. Responsibility for Javier’s life is passed from one migrant to another, sometimes with care, others with exasperation and frustration.

Reading about such a dangerous and terrifying experience as crossing a border illegally through the eyes of a child was astounding. It is a perspective of migration I have not encountered before; most migrant memoirs and fiction I have encountered have always been from the perspective of a late adolescence or adult. It invites the question, how do you view something like crossing a border illegally if you’re too young to understand the realities of what's going on?

Javier delicately weaves this childhood innocence throughout the story, reminding you at some incredibly dangerous moments, how he feels about what was going on. Before Javier boards for a boat crossing, he tells us how ‘he’s scared of sharks’. When coyotes tell him to shower, he tells us how he doesn’t know how to properly wash himself or his clothes.1 Javier is left to his own devices to look after himself, and shares how he is scared of the toilet flush and can’t tie his shoes. These normal thoughts and feelings of a nine year old boy consistently contrast the serious nature of what is going on. The distress and terror of the crossing felt by the adults around him bleeds from the page, but Javier interprets these frustrations and emotions as him being disliked. The contrast between the realities of what's going on and how Javier is feeling is painful to read.

We learn how Javier’s predominant understanding of crossing the border is adapted from popular culture, reinforcing his youth and innocence. When Javier reaches the desert, it is sobering to read how he believed the border crossing would go;

‘I thought my parents were going to be right over the fence waiting for me in their car after I jumped it. But there is no fence and no asphalt road with a McDonald’s parking lot on the other side.’ ‘No green hills like Born in East LA and no faint steel fence to jump’.

Through watching some clips of ‘Born in East LA’ it is clear how Javier would have perceived this crossing to have gone. Popular culture would have entirely shaped his understanding of America and migration. For anyone curious, here is the trailer for ‘Born in East LA’:

‘Solito’ is an important and emotive read. I recommend it wholeheartedly and cannot imagine anyone not enjoying this book. ‘Solito’ is a complete buy. It is educational, interesting and compelling. Despite the harrowing subject matter, there is hope and love throughout the story. A mother and daughter named Patricia and Carla and a man named Chino look after Javier to ensure his safety at every turn. The kindness they extend to Javier despite the petrifying nature of what was going on is moving. Javier hopes through sharing his story he will be reunited with Patricia, Carla and Chino as he hasn’t seen them since the crossing. Reading this made me bawl my eyes out and I hope ‘Solito’ becoming a New York Times bestseller reunites him with those he made such a life changing journey with.

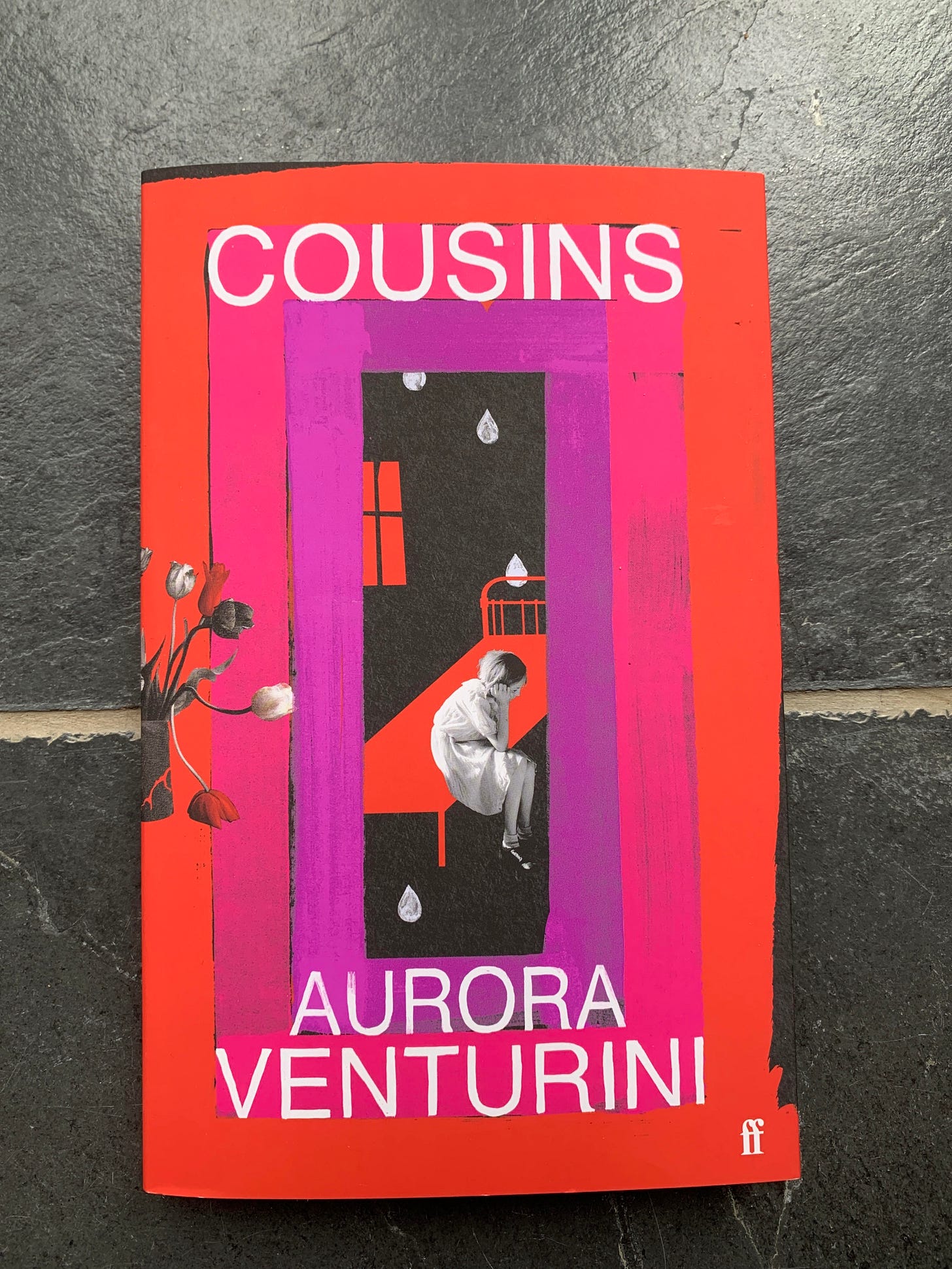

‘Cousins’ by Aurora Venturini. ‘Cousins’ is a bizarre and brutal story of an impoverished family of dysfunctional women outside Buenos Aires. These women suffer extensive abuse at the hands of men and many hardships, such as disfigurement, illegal abortion, sexual abuse and murder. We follow our narrator, Yuna, from early adolescence into adulthood as she observes what is happening to her and her family. Yuna has great artistic promise, and after an art teacher believes in her, Yuna’s success as a painter offers a way out of her family’s fate. She uses her achieved economic independence to help her family as best she can.

‘Cousins’ is full of black humour on misogyny, abuse and disability. The topics in this book are very dark and confronting, but Yuna’s child-like narration and innocence masks the true nature of what’s happening to her family. The evolution of Yuna’s writing style and prose reflects her maturity as she grows up. Initially, our protagonist's description of scenarios and her family feels jarring and strange as it is akin to stream of consciousness. As Yuna matures, and discovers a dictionary, it develops into a more traditional writing style, with more emotionally intelligent observations. We witness Yuna grow up through her writing style and prose, expertly done by Venturini.

There is a noticeable narrative shift when she realises the weight of the injustices befalling her family. Yuna’s voice is incredibly odd and takes a moment to get used to, but eventually feels endearing. I wouldn’t recommend this to everyone, ‘Cousins’ is definitely a more peculiar read. It reminded me slightly of Ottessa Moshfegh style of writing with grotesque and confronting content.

Despite its peculiar nature I would recommend this book and call it a buy. I enjoyed the shocking journey Yuna took me on. ‘Cousins’ won an award in 2007 and the author Aurora Venturini was revealed to be 85 years old, and it was only then that Venturini was widely recognised for her talent and radical voice. And that's pretty epic and makes me even more fascinated in her and her work.

‘Russian Gothic’ by Aleksandr Skorobogatov. ‘Russian Gothic’ was first published in 1991 and has recently been translated into English for the first time. ‘Russian Gothic’ won ‘Best Novel of the Year’ from Yuonst in Russia in 1991 and Skorobogatov is widely acclaimed to be a remarkable writer. ‘Russian Gothic’ is a dark and tragic tale of alcoholism. It centres on the grief-stricken and violent marriage of Nikolai and Vera, blown apart by jealousy and paranoia. An unknown visitor called ‘Sergeant Bertrand’ frequently appears in Nikolai and Vera’s flat.

After the first chapter it is clear that ‘Sergeant Bertrand’ is part of a succession of delusions by Nikolai who is an alcohol-addict with a terrible jealousy obsession. Bertrand is lusting after Vera, takes control of Nikolai’s mind and undermines and manipulates him with foul insinuations. Nikolai lapses into sudden outbursts of brutality and violence as he is consumed by paranoia. Despite his nature, Vera holds an insane amount of unconditional love for her husband. Nikolai’s delusions are a complex portrayal of grief, misogyny and violence.

This read was okay. It is a gloomy tale of a world of destructive emotions and brutal violence. ‘Russian Gothic’ was interesting and creative, but also incredibly violent and at times hard to follow as it is not entirely clear where Nikolai’s delusions end and the real world begins. Although I am aware that that was the point of the writing, enveloping us into a heightened sense of confusion to reflect Nikolai’s psyche as a substance abuser. It was interesting and different but I am not entirely sure how much I’d recommend it.

For me, ‘Russian Gothic’ is a borrow. Russian literature is known for its incredibly bleak nature and this lived up to all stereotypes. I read one review that suggested this novel could be read metaphorically. To see Nikolai/Bertrand as the obsessive and ruthless state, operating jealousy and violently towards its inhabitants, a late reminiscence of the Soviet Union. This is a really thought provoking take and could elicit an entirely different reading experience if I picked this book up again. I’m open to trying again in a year or two once I’ve forgotten some of the more violent scenes.

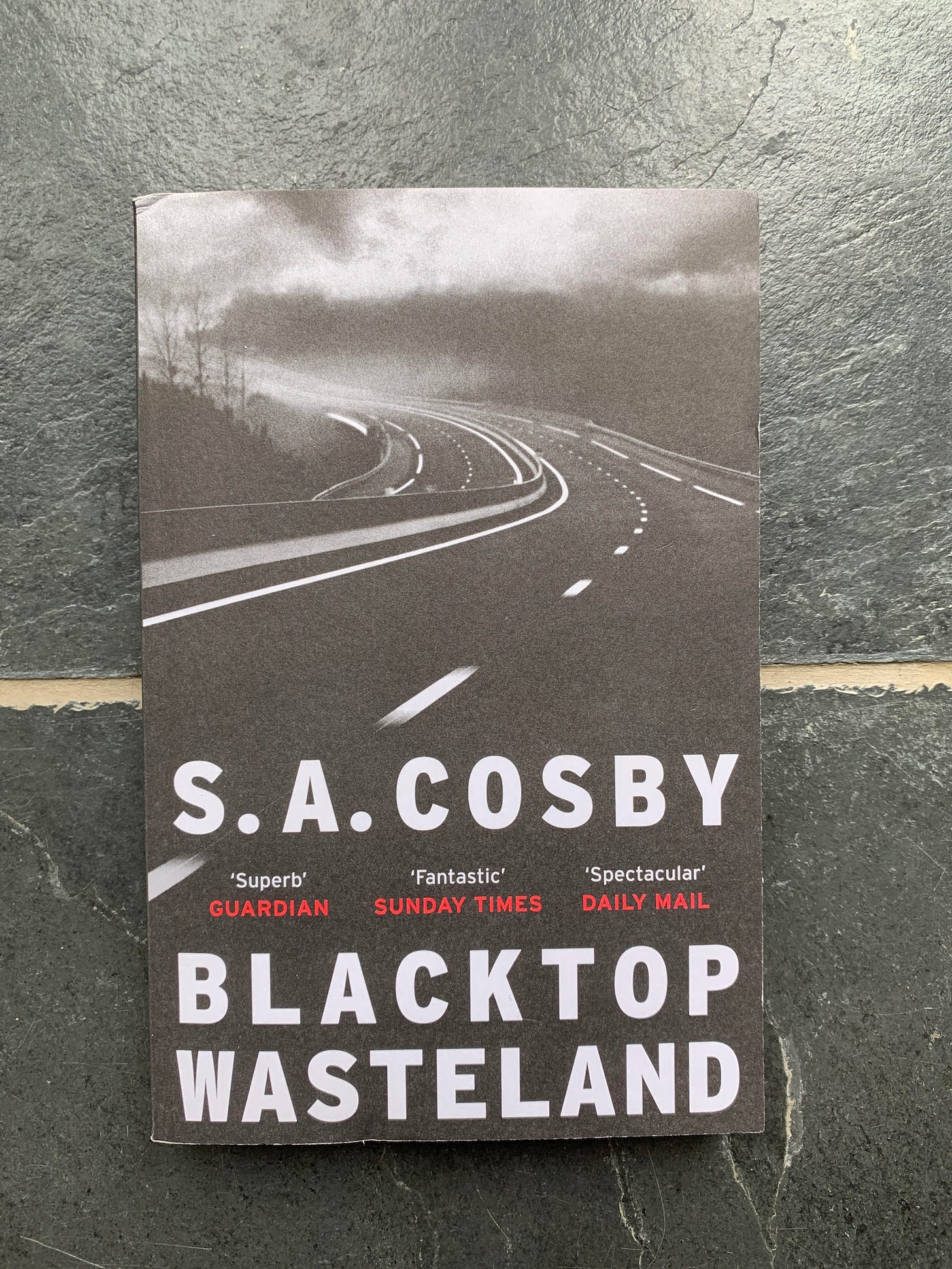

‘Blacktop Wasteland’ S.A. Crosby. ‘Blacktop Wasteland’ was the best book I read this month. It is about a car mechanic named Beauregard ‘Bug’ Montage. Bug was infamously known far and wide as the best getaway driver on the East Coast, just like his father who disappeared many years ago. However, since having a family, Bug devotes himself to trying to become everything his father wasn’t; an attentive husband, responsible parent and a respectable small business owner. But Bug and his family are trapped in a relentless cycle of poverty, worsened by the racial prejudices of the small town he lives in. As a series of financial demands start to pile on his shoulders, Bug cannot make ends meet. So, he reluctantly decides to take part in one last job. Bug takes part in a diamond heist to solve his money troubles once and for all.

However, it goes horrifically wrong and threatens to destabilise the life he has worked so hard to build. A life he wanted so desperately to not turn out like his fathers. ‘Blacktop Wasteland’ is a searing story of a man pushed to his limits by poverty, race and his former life of crime.

‘Blacktop Wasteland’ is the best thriller I have ever read. I don’t think I have ever had so much adrenaline pumping through my body reading a book as this one. Now I bet you’re thinking; Martha a book about a car mechanic can’t possibly be this exciting? Well trust me, it is. Cosby’s vivid and dynamic writing creates such a captivatingly dark and intense crime world. Bug is such an endearing character who you instantly fall in love with, he is a good man who has been dealt a terrible hand. At its core, ‘Blacktop Wasteland’ is about poverty and masculinity and how the two interplay. Cosby said;

‘Blacktop Wasteland is about the hereditary disease that is poverty, but it’s also about the violent inheritance that damaged men pass onto their sons.’

This contrast of such emotional and delicate themes with such raw and harsh violence creates such an enchanting read. Cosby’s incredible writing completely seduces you into not being able to put the book down. ‘Blacktop Wasteland’ is a total buy. Immediately after putting this book down, I ordered ‘Razorblade Tears’ so I will be reading that before the year is out. I was so blown away by Cosby’s writing and skill in crafting so much adrenaline and tension on the page. His talent is exceptional. If I had to only recommend one book from my September reads, it would be this one.

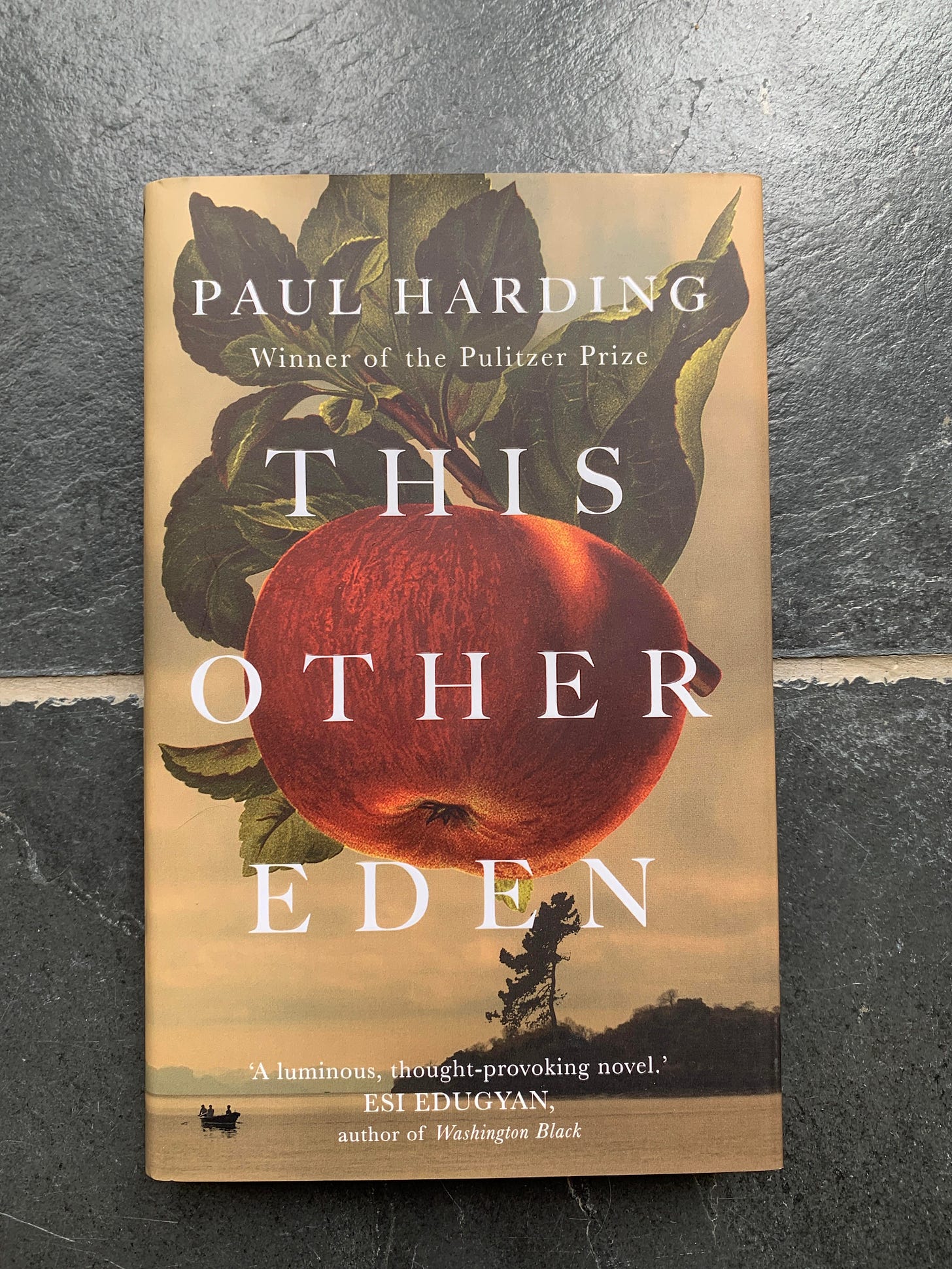

‘This Other Eden’ by Paul Harding. Shortlisted for The Booker Prize 2023 ‘This Other Eden’ is the fictionalised story of an isolated interracial fishing community living off the coast of Maine. In 1792, formerly enslaved Benjamin Honey and his Irish wife, Patience, discovered an island where they could make a life together. More than a century later, Honey’s descendants remain there. They live peacefully and happily within their abnormal, eccentric and isolated community. However, eugenics-minded state officials are determined to cleanse the island. A missionary school teacher chooses one light-skinned boy to be saved, while the rest succumb to the authorities' institutions or cast themselves out to sea. ‘This Other Eden’ examines what happens when societal standards, driven by the rise of eugenics after the American Civil War, are forced on a rural and isolated integrated community.

‘This Other Eden’ is based on the real story of Malaga Island that was home to a mixed race fishing community from 1800 to 1912, when the state of Maine evicted 47 residents from their homes and exhumed and relocated their buried dead. This violent act was motivated by racism, eugenics and Maine’s tourism industry. You can read about the incredibly fascinating and tragic history of Malaga Island here.

Back to Harding’s reimagined take of the island. ‘This Other Eden’ is a lyrical and emotionally woven story. Harding interprets these horrific true events by creating fictional characters and lyrical prose. The violent and inhumane cruelty of this eviction is sharply contrasted with heavy biblical imagery. It is definitely an interesting interpretation, one that felt simultaneously poetic and reductive. I think Harding made the right call by fictionalising the name of the island as well as the individuals written about. He withholds judgement on the enablers and victims of the island's tragedy, gracefully and empathetically writing about all the characters. However, I found the premise of the book and the history of the island more compelling than Harding’s reimagined story. Occasionally I was incredibly moved by the writing, others I was less compelled by the way he chose to interpret the events.

I also question whether it is appropriate for Harding to be the one telling this story. There are questions of agency and nuances of race and poverty which are not explored deeply enough in the novel, making the text feel at times a little simplistic. Harding’s storytelling is beautiful, but perhaps feels lacking once you know the history of the island. Yet, I do appreciate that Harding set out to write a beautiful and lyrical piece of story telling and not a history book. ‘This Other Eden’ reads as a conventional historical novel and I’d call it a borrow. I did enjoy reading it and the history I learnt of Malaga Island, but I anticipated substantial depth and the book falls short of this story's potential. I do think it’s worth a read, but I would be surprised if this won the Booker Prize.

‘The Sirens of Titan’ by Kurt Vonnegut Jr. ‘The Sirens of Titan’ was Vonnegut’s second novel and is a satirical science fiction story about the purpose of mankind, offering commentary on human intelligence and foolishness. It is about a man named Winston Niles Rumfoord, who flies his spacecraft into a chronosynclastic infundibulum where he is converted into pure energy. Because of this, Rumfoord only materialises when his waveforms intercept Earth or another planet. As a result, he comes home to Newport, Rhode Island once every 59 days and only for an hour. He also now knows everything that has ever happened or that will ever happen.

Throughout the novel he predicts events, and these predictions come true. One day while materialising, Rumfoord meets Malachi Constant, a man who possesses extraordinary luck. Rumfoord tells Constant that he will die on a planet called Titan, be part of a Martian invasion and have a child with Rumfoord’s wife; Beatrice. Constant dismisses Rumfoord’s ludicrous predictions, but as soon as he leaves he encounters a threat of violence where he holds no fear because he knows he will not die on Earth, Constant realises Rumfoord might be telling the truth. And that his life might not be so lucky.

After reading my first Vonnegut last month, I wanted more. However this didn’t really live up to expectations. It has been said that Vonnegut put together ‘The Sirens of Titan’ in one night; someone told him to write another novel at a party so he went into the next room and pieced together a book from the things that were on his mind. After reading this comment, I am inclined to believe it. The novel contains enough ideas for half a dozen normal books. I was so impressed by the themes, but I struggled with the chronology and following the storyline.

Most of the time reading this I was incredibly confused (writing the plot summary you have just read was a lot harder than I’d be willing to admit). ‘The Sirens of Titan’ holds immense thought provoking and philosophical questions. Questions of free will and lack of agency, which are well known hallmark themes to Vonnegut’s work, permeated the story. However I couldn’t get on with this story, I wouldn’t recommend it, despite how much I have enjoyed Vonnegut’s work before. I’d call ‘The Sirens of Titan’ a bust. Reading this book was hard work, and not the good kind.

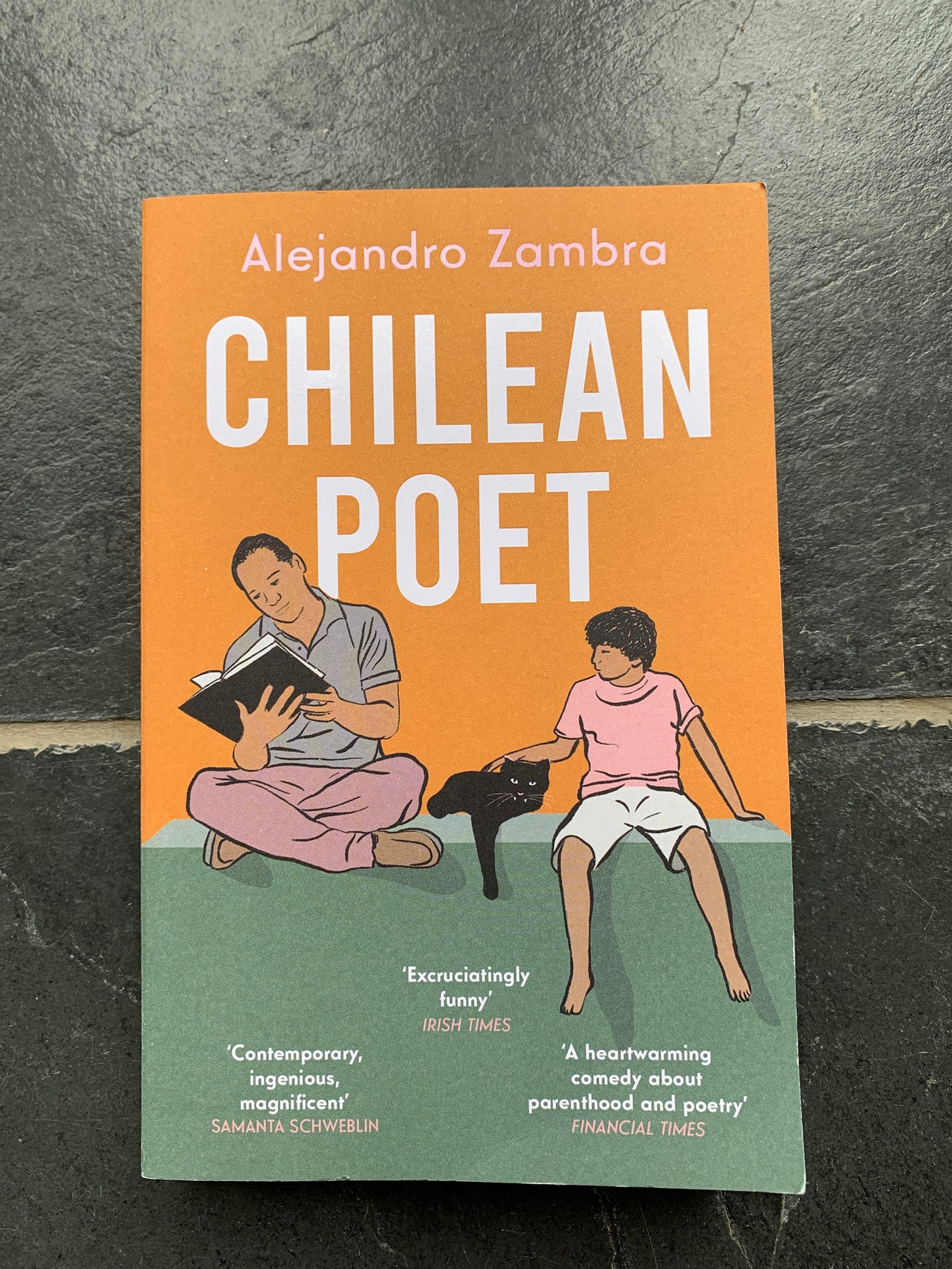

‘Chilean Poet’ by Alejandro Zambra. ‘Chilean Poet’ is about Gonzalo and Carla, a couple who hook up as teenagers and then meet again several years later in their twenties. They fall in love and Gonzalo becomes a step-father to her son, Vicente. Soon the three form a happy and loving step-family. Gonzalo’s developing relationship with Vicente is endearing and a joy to read. Eventually Gonzalo and Carla’s own ambitions pull the lovers in different directions, splintering the family they created and Gonzalo’s role as a step-parent. Gonzalo moves to New York to become a poet, but misses his relationship with Vicente deeply.

When Vicente grows up, he inherits his ex-stepfathers love of poetry. The latter half of our novel charts 19 year-old Vicente’s foray into the poetry world. He meets a journalist called Pru who wants to do an investigative piece on poets in Chile. As Vicente starts to explore who he is and his passion for poetry, he realises it might bring him back to Gonzalo.

‘Chilean Poet’ is a sweet and endearing contemporary about parenthood and poetry. It’s a playful and heartwarming. The relationship focus of the story is not of Gonzalo and Carla, but of Gonzalo and Vicente. It is unusual to read such a touching story of a relationship between a step-parent and child, especially father and son. Zambra’s exploration of parenting and the relationship between different generations of male writers is said to represent two versions of Chile itself, from dictatorship to democracy. ‘Chilean Poet’ was good but not much more than that. I enjoyed Gonzalo’s narration the most at the beginning, but felt the story started to fall flat with Pru’s narration in the middle. I felt Vicente’s narration at the end was only engaging because of the imminent reunion with Gonzalo. At times the story felt slightly directionless. I’d call ‘Chilean Poet’ a borrow. The poetry Zambra wrote in the book was really beautiful and I enjoyed the exploration of the significance of poetry throughout the narrative. But the story as a whole was average and not consistently captivating.

‘The Twilight Zone’ by Nona Fernández. After several average reads in a row, I really wanted ‘The Twilight Zone’ to break that cycle, and it did. A finalist for the 2021 National Book Award for Translated Fiction ‘The Twilight Zone’ follows our author's life-long obsession with a member of the Chilean secret police, who confessed to participating in some of the worst crimes committed by Augusto Pinochet's military dictatorship. In 1984, at the height of Pinochet’s dictatorship, a member of the secret police walked into the office of Cauce, a dissident magazine, and recorded his testimony.

This event is the point of inspiration for ‘The Twilight Zone’, and is primarily an investigation into Andrés Antonio Valenzuela Morales’s role during the Pinochet dictatorship. This soldier's testimony served as a catalyst to the downfall of the regime. You can read the original Cauce interview here.

The dictatorship lasted for 17 years between September 1973 and March 1990. This dictatorship is characterised by the enormous persecution of dissidents and crimes against humanity. Overall the regime left over 3,000 dead or missing, tortured tens of thousands of prisoners and drove an estimated 200,000 Chileans into exile.

Fernández was a child when ‘the man who tortured people’s’ testimony revealed Morales’s criminal complicity in the regime. The story is constructed from the Cauce testimony, historical archives and the author's personal experience. Through this the reader is encompassed into life under the dictatorship. The story asks; how do you resist a repressive regime? And how do crimes vanish in plain sight? In the face of historical erasure, ‘The Twilight Zone’ brings to life the people who the Pinochet dictatorship destroyed.

‘The Twilight Zone’ was an incredibly captivating and moving read. There is impressive nuance throughout the book as she depicts everyone, victims or members of the regime, as human beings struggling with the enforced realities of the dictatorship. It is an unflinching, emotionally moving and effective story of such a brutal time in Chilean history. The subject matter is harrowing and Fernández does not shy away from the realities of life under military dictatorship.

Fernández uses a variety of lenses to view the stories; such as pop culture and video games. The writing beautifully contrasts with the ugliness of the content. It is experimental and unlike any historical fiction I’ve read before and I was engrossed with the storytelling from page 1. I would recommend this book and call it a buy. It was a really great read, one I would recommend to readers who enjoy historical and dystopian fiction. It felt very Orwellian. Incidentally, 1984 was when the Cauce interview came out.

‘A Minor Chorus’ by Billy-Ray Belcourt was my final read of September. Belcourt’s debut novel and winner of the 2023 BC and Yukon Ethel Wilson Prize ‘A Minor Chorus’ is a beautiful book. In Northern Alberta, a queer Cree doctoral student chooses to step away from his dissertation and write a novel. Our unnamed narrator chronicles a series of encounters, including the mounting pressure put on marginalised scholars and the vulnerability and loneliness that closeted queer life looks like.

The narration touches on a lot of different facets of the Indigenous experience, centred around their hometown. Amid these conversations, our narrator is haunted by their cousin Jack, who was caught in the cycle of police violence, drugs and survival. Through these themes our narrator shines a light on the realities of Indigenous survival and the legacies colonialism has left behind. Our narrator ponders the prisons we live in and the realities of living amongst a settler society.

‘A Minor Chorus’ is a poetic and elegant book full of captivating and individual storylines which serve the same collective narrative. The book tells the stories of minorities, exploring the loneliness and oppression that can be felt collectively by a group. ‘A Minor Chorus’ touches on the story of an indigenous population that was subjugated by invading colonial powers, and how the population were mistreated and incarcerated on reserves. There is a long history is Indigenous people being treated horrifically by law enforcement, in and outside of prison. Belcourt writes about these themes compelling with grace and dignity.

This book is so lyrically written, managing to put these really raw and complex emotions on the page in a way that is truly touching. My only criticism is I wish it was longer! I wanted to spend more time with our narrator and their community as the stories were so captivating. ‘A Minor Chorus’ is a total buy. I would really recommend it, particularly to lovers of lyrical and contemporary fiction.

And that concludes my September reads! My favourite read of this month was ‘Blacktop Wasteland’. Thank you for reading this newsletter, I really appreciate it. My first read for October is ‘Ring Shout’ by P. Djèlí Clark, a dystopian story of the reconstruction/turn of the 20th century American South where the Ku Klux Klan is active, and members of the Klan mysteriously turn into ravenous monsters. Our protagonists are a group of friends who are Klan monster hunters.

Let me know what you have read and enjoyed in September, or which book from this newsletter you’d most like to read. I’d love to know!

Happy Reading! Love Martha

Want to read more Martha’s Monthly content? Catch up on what you might have missed here:

Colloquially a coyote is a person who smuggles immigrants across the Mexico-United States border

Agree with your take on Russian Gothic. I enjoyed the abstraction but found really nothing to tether to outside of the circular violence. I haven’t read much Russian Literature so I’m interested to see how it holds up as I dive into those classics.

I thought I had read most of Vonnegut’s novels years ago, but your description of Sirens of Titans doesn’t sound familiar, so probably I didn’t.

I had kind of forgotten about Vonnegut, but recently watched the new documentary, Unstuck in Time. A thorough, personal look at Vonnegut over the years and a little heartbreaking too. Recommended to anyone familiar with his work. It should be on Hulu.