April Reads

Displacement, racial identity and the sentiment of belonging + my thoughts on the International Booker Prize Shortlist

Welcome to Martha’s Monthly, April Reads edition! Belonging was a prevalent theme in the books I read this month. Several books explored feelings of displacement, racial identity and the alienation children feel when confronted with an adult world.

To see the translated reads from April on Martha’s Map, including authors from Colombia, Angola, Netherlands, Vietnam and Germany, click here.

For those who are new, buy, borrow, bust is my recommendation key. Buy = I immensely enjoyed and heavily recommend this book. Borrow = I think this book is still well worth a read and I’m glad I read it. Bust = I wouldn’t recommend this book from my own reading experience.

The newsletter is slightly longer this month. I read 10 books and I wanted to give my thoughts on the International Booker Shortlist for anyone whose interested. Sue me for being a passionate reader.

On with the show!

‘Birnam Wood’ by Eleanor Catton. Five years ago, Mira Bunting founded a guerrilla gardening group called Birnam Wood. An undeclared, unregulated, sometimes criminal and sometimes philanthropic activist collective who plant crops wherever no one will notice. For years the group has struggled to break even. Then Mira stumbles on an answer, a way to set the group up for the long term. A landslide on New Zealand's South Island has caused a sizeable farm to be left seemingly abandoned, creating an opportunity. However, Birnam Wood are not the only ones interested. Robert Lemoine, an enigmatic American Billionaire, also has plans for the farm. Intrigued by Mira, Birnam Wood and their entrepreneurial spirit, Lemoine suggests they work together. But can a guerrilla gardening group trust a billionaire? The arrival of Lemoine tests the ideals and ideologies of the group, and Birnam Wood are forced to confront whether they can trust each other.

The first half of the novel is slow moving as we are plunged into excessive detail of the minds of our protagonists, learning about their emotions, relationships, beliefs and worries. Catton very intentionally spins a world of misunderstanding, where every character is set up to antagonise and irritate someone else. Through this spectacular character immersion, ‘Birnam Wood’ steadily builds a gripping timeline that culminates in the second half of the novel. This pacing structure creates a reading experience that doesn't feel dissimilar to climbing up an incredibly steep mountain, only to rapidly fly down the other side. Initially I did not favour the structure and lack of chapters, however retrospectively the structure was essential for creating the relationship-driven tragedy. Without this meticulously created exploration of heightened emotions, the climax of the novel could not have been reached.

‘Birnam Wood’ is a unique thriller that centres around an ensemble of antiheroes who are all as equally self obsessed and vapid as each other. The sentiment of tragic heroism runs parallel to the group's choice of name ‘Birnam Wood’ which is taken from Shakespeare’s ‘Macbeth’. Catton said she saw ‘Macbeth’ as ‘a play about the dangers about having a sense of certainty about the future’.1 This sentiment of arrogance about the certainty of the future is embodied by both Lemoine and Mira. Both characters believe the other is ignorant in how they see the world. Catton said in ‘Birnam Wood’ she wanted to explore, in good jest, the deadlocks of our contemporary politics.

I was surprised to learn that Catton intended for the novel to ‘ask political questions without itself being partisan’. 2 I can appreciate Catton’s attempt to comment on the polarising nature of the current political landscape; writing a fable on the destructive nature of political deadlock. Mira and Lemoine both act as examples of individuals too obsessed with their own ideologies to see the nuance required to make impactful change. However, to me the only political question Catton asks is not one of politics at all, but one of questioning our human nature. I would argue she is suggesting that flawed human nature is central to the political flaws we see play out across the world, rather than the extremities of political ideology itself.

While the political ideology of the characters is never explicitly renounced, and rather assumed, it is difficult for Catton to create impartiality, and ask political questions, surrounding the ethics of being a billionaire. A billionaire's financial status is indicative of wider societal imbalance. Ultimately, Lemoine represented a potential avenue for Catton to interrogate the ethics of being a billionaire and the relationship with politics. However, I would argue his characterisation fell short of this. I did not feel that any political questions were asked in relation to Lemoine. How can Catton write a book about climate change, and a billionaire, and not address the direct relationship they have to the changing of the planet?

Despite my criticisms of Catton's political intention of the novel, her penmanship is fantastic. The skill required to craft such tension, jealousy and misunderstanding on the page is remarkable. ‘Birnam Wood’ is a book that rewards you for reading such extensive character analysis with a gripping end. Catton said she wanted to ‘write a book that gave people a good time, was thrilling, surprising, bloodthirsty and good fun’ and she absolutely delivered on this intention.3 I would call ‘Birnam Wood’ a buy for its entertaining nature. I would recommend it if you enjoy in depth character analysis and dramatic twists. Several of you have told me you have read ‘Birnam Wood’ last month so I would love to know what you think of my analysis! Let me know in the comments.

‘If Beale Street Could Talk’ by James Baldwin was my third classic novel of the year. This novel is a story of the enduring power of love and family against a backdrop of racial and class discrimination. Our protagonist, Tish, is nineteen, pregnant and living in Harlem in the early 1970s. Her lover, Fonny, father of her unborn child, is in jail accused of rape. Flashbacks from their love affair are woven into the compelling struggle of a family attempting to win justice for Fonny. Baldwin writes not only about the love within romantic relationships, but a love within familial relationships.

‘If Beale Street Could Talk’ is a mediation on the horrors of the criminal justice system. Tish and Fonny are the hands of an enormous miscarriage of justice; a universal vulnerability for the black community in the 1970s.4 Baldwin tells the story of how institutional discrimination has the power to destroy lives, humanising the victims on the other side of the prison statistics. The storyline of a black man accused of raping a white woman in this time era is profound, because Baldwin has given us the verdict before we have even read the book. We as the reader know that the system will do anything to keep Fonny in prison and he will not be able to collect enough evidence to get out. It is clear that Fonny has been set up to take the blame for the rape - the victim identified her attacker as black and Fonny was the only black man chosen by the police to be in the lineup. By starting the book knowing Fonny’s fate, Baldwin creates a very different narrative; one where we are reading not for the outcome of the case, but in search of who Fonny is outside of the stereotypical attributes he is ascribed as a black man under institutional racism. Baldwin is inviting us to consider who Fonny is as a human being.

Along with inviting us to humanise Fonny, Baldwin explores the impact on the family. Baldwin seeks to represent how multiple lives are ruined by institutional discrimination, not just the life of the accused. ‘If Beale Street Could Talk’ explores the impact on Tish, her unborn child and their combined families. They are all individuals just trying to survive in a world of monumental injustice. Baldwin eloquently presents a humanised take on the prison system and the vulnerability not just black individuals, but the entire black community, have when it comes to the criminal justice system. Published in 1974, this book was unprecedented as Baldwin confronts American society with the horrors of institutionalised racism, humanising those put behind bars because of the colour of their skin. Baldwin approaches the topic with significant nuance by exploring the heartbreaking impact of systemic racism on the families of those imprisoned. He devastatingly articulates how hope is vital for the family, despite knowing the hopelessness of the situation.

Baldwin’s writing was beautiful and compelling throughout. I was expecting to be moved as profoundly as I was when reading ‘Giovanni’s Room’, which is a fault of my own, and therefore made the experience of reading slightly disappointing. I wanted to feel more connected to Fonny and Tish than I did, and ultimately thought Tish’s mother Shanon was the most compelling character. Baldwin is in a league of his own and could never write a bad book, however this didn’t capture me as much as I thought it would. I would still recommend it for the approach to the themes it tackles, but would call it a borrow. Does anyone have any suggestions of what Baldwin I should read next?

‘Abyss’ by Pilar Quintana is a literary exploration of a young girl’s experience with familial depression. Claudia is an impressionable eight-year-old girl trying to understand the world through the eyes of the adults around her. ‘Abyss’ tells the story of Claudia’s acute observations of her parents. Her hardworking father hardly speaks a word, while her unhappy mother spends her days reading celebrity lifestyle magazines. She tends to her plants and fills Claudia’s head with stories about women who end their lives in tragic ways. Then an interloper arrives, disturbing the delicate balance of family life, and Claudia’s world starts falling apart.

Claudia’s observations of her parents remind us that children are capable of discerning extremely complex realities even if they cannot fully understand them. Claudia’s mother is asphyxiated by the prescribed gender roles in Colombia in the 1980s and as a result is struggling with depression. Claudia can sense this, but it is never explained to her. Through Claudia’s eyes we are taken into the mind of a child trying to interpret depressive behaviours demonstrated by her mother. The sentiment of women being suffocated culturally and socially in Colombia reminded me deeply of 'December Breeze’ by Marvel Moreno. Both books explore the impact of women being suffocated by Colombian society; unable to gain control of their own lives, they are driven by fear, loneliness and mental illness. Often at the whims of men and motherhood, these women are expected to be satisfied and desire nothing more.

Claudia’s perspective of her mother is subtle and devastating, equally sweet and sad. Ultimately Claudia does not know exactly what is happening, but she understands enough. ‘Abyss’ speaks to the idea that children know more than adults believe they do about what's going on around them. Claudia suggests that even though she does not have the exact terminology for ‘depression’, she knows what’s going on. Claudia’s mother is presented to be wilful and ambitious, with her aspiration being trodden on by the stifling restrictions of living under a traditionally patriarchal society.

Quintana writes the confusion and frustration Claudia feels about not being spoken too directly incredibly well. Quintana said ‘Abyss’ is a response to the fear many children have about being abandoned. Quintana explores the intensity of Claudia’s desires, from the ecstasy of owning particular trainers to the intensity of the dark emotions she feels; why doesn’t her mother get out of bed and what does it mean to want to die? This emotional range is so universal for children - the world is full of so many questions that adults avoid to answer, it's frustrating and isolating. Quintana’s writing was deeply passionate, gentle and compelling. I loved this book and the exploration of gender roles in Colombian society in the 1980s through the eyes of a child. Claudia was a protagonist that was a joy to spend time with on the page. I was endeared by her perspective and compelled by her quest to understand what the adults around her refuse to tell her. Quintana captured the childlike fascination with death and despair perfectly.

‘Abyss’ is about staring into the abyss as a child because serious ‘adult’ topics are not explained to you. I loved reading this book, full of lucidity, innocence and suspense. Claudia’s outlook on the world is ruthless and true. May I never underestimate a child's ability to discern what's happening around them again. I would absolutely recommend ‘Abyss’ and call it a buy. A wonderful novel that is in equal parts dark and uplifting as we are enveloped into a family full of secrets.

‘Transparent City’ by Ondjaki tells a unique story exploring the impact of corruption on people and society. In a crumbling apartment block in the Angolan city of Luanda, families work, laugh and scheme to get by. In the middle of it all is Odonato, a man nostalgic for the country of his youth and searching for his lost son. As his hope drains away, and the city outside his doors changes beyond all recognition, Odonato’s flesh becomes transparent and his body increasingly weightless. Blending magical realism and scathing political satire, Ondjaki offers a portrait of urban Africa.

‘Transparent City’ is a state of the nation novel - a nation that is crumbling at the hands of market capitalism. It explores corruption and exploitation at every level, including politicians, business men and scientists. ‘Transparent City’ paints a picture of an apocalyptic future where even water has been privatised; a fable for where we might be heading. Ondjaki explores the idea that our humanity is at risk the more and more market capitalism exists, our souls and essence as beings is under threat;

‘to imagine, to imagine….making use of the faculty that separates us from other beings, [...] the flower doesn’t imagine, it blossoms, the bird migrates, the whale swims, the horse runs, we imagine before we migrate, we can imagine while we swim, and by imagining we can discover countless new ways of running, or even of taming a horse and making him run with us, we had to imagine it all in advance, and that’s the beauty of the human condition, it’s part of our condition as free beings, prisoners, recluses, the ill, in the last moment of our days we’re imagining… and that's what science and humanity need: imagination’ p.105 in ‘Transparent City’

Odonato is the only character who is able to coherently remember a society before mass exploitation and corruption. He yearns for a country to be rich in the warmth of community and humanity. Instead, the city of Luanda is bursting at the seams with officials intoxicated with power and profit hungry schemes, and those who are not profitable are deemed worthless, and that is why Odonato is disappearing;

‘we aren’t transparent because we don’t eat… we’re transparent because we’re poor’ p.163 in ‘Transparent City’

‘Transparent City’ harbours an ambitious and sharp concept. Ondjaki’s approach to exploring corruption, especially within African cities, was deeply funny, confronting and conceivable. Official corruption has been widespread in new African cities in the postcolonial period and has contributed significantly to political instability and public distrust of the governments. Angola ranks considerably high on the Corruption Perceptions Index.5 Former president of Angola, Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who was leader of the country following independence from 1975 to 2017, amassed a personal fortune by exploiting the nation’s oil wealth. While the country’s elite became increasingly wealthy from this, most Angolans lived on less and $2 a day.6 ‘Transparent City’ is a very thought provoking and imaginative take on the behaviour of dos Santos, as well as a plethora of other corruptive leaders across the continent.

‘Transparent City’ was unlike anything I have ever read. It took a while to get into it, but I was compelled by the story and the characters. Stylistically the novel included limited punctuation, capital letters or structure. This made it a slight challenge to read, especially when there were around fifteen characters to keep up with. I interpreted the overlapping prose and sparse punctuation to give a sense of humanity in constant motion; or more aptly, constant chaos. The lack of structure on the page was mirroring the complete lack of regulation within Luanda. I would be lying if I said it wasn’t hard work to read this, because it was. You really have to focus because there is lots going on. But from great concentration comes great reward as we are enveloped in a world of profound chaos that critically examines the state of life under capitalism.

I enjoyed the concept, messaging and tone of ‘Transparent City’ and would call it a borrow. I would recommend this book to anyone who enjoys political and dystopian fiction, as well as magical realism. When I was reading this I couldn’t help but keep thinking how well it would have fitted last month's existentialism theme. If you enjoyed my reflections on capitalism in March, I think you’d enjoy this.

‘What I’d Rather Not Think About’ by Jente Posthuma is a story about life, death and survival. Our protagonist is a twin whose brother has recently taken his own life. She looks back on their past, desperately examining where their paths diverged. Through brief vignettes she recounts how her brother tried to find happiness, but lost himself several times along the way. Full of melancholy and humour, our protagonist tells the story of a depressive brother and examines what happens between twins, who are believed to be so intrinsically connected, when one half no longer wants to live.

Our protagonist has to grapple with the fact that the person she has shared every experience with has chosen to die. She is having to work out how to survive going forward and how grief permeates every aspect of her life. She starts to consider grief in everything, from the inexplicit, like the TV show ‘Survivor’, to the explicit, like visiting the 9/11 memorial in New York because they were both fascinated by the attack. ‘What I’d Rather Not Think About’ explores abandonment, through the abandonment from their parents to the abandonment she feels through her brother leaving. Posthuma explores the bond that the twins have, as our protagonist suffers greatly in the wake of his death and feels like a piece of her is missing.

The first word of this novel is ‘waterboarding’, and that sets the tone of how she is feeling suffocated by her twin’s death. Posthuma focuses on interesting examples of ‘twins’, such as the Twin Towers and Josef Mengele’s experimentation on twins in the Holocaust. Our protagonist has a fascination with the Holocaust and the impact it had on the survivors. To me it felt like she was trying to understand her pain, by attempting to hierarchise suffering to interpret how she should be feeling. She is trying to measure and reason with her grief and pain with a genocide in order to try a convince herself that her grief and trauma is not ‘that bad’ (for lack of a better phrase). I can understand the author's intentions here, there is no suffering hierarchy and all grief and pain is valid and different. I think it opens an interesting discussion around what it means to be traumatised. However, it felt unnecessary to compare the suicide of her brother to events of the holocaust; they are incomparable in nature. I appreciate that is the sentiment that the author is trying to communicate, but at times it didn’t feel as sophisticated and nuanced as perhaps intended it to be.

Our protagonist feels like she has failed her brother by failing to prevent his suicide. It feels wrong that she did not know intimately how her twin was feeling at all times. However, what I think Posthuma is trying to achieve is the sentiment that you will never find the answer by looking back critically. Posthuma’s writing is striking in its simplicity. The book grapples with enormous grief and enormous love, exploring how they are two sides of the same coin. I enjoyed this book and stylistically I thought the approach of repetitive vignettes to explore grief was very well done, because grief is so often incoherent snapshots. I would recommend ‘What I’d Rather Not Think About’ to anyone who's interested in explorations of grief and would call it a borrow - it was very easy to read.

‘The Colour of Water’ by James McBride.7 Growing up in Brooklyn’s Red Hook Projects, James McBride knew his mother was different. Ruth McBride Jordan was evasive about her ethnicity, yet steadfast in her love for her twelve children. The son of a black minister and a white woman who refused to discuss race, James McBride grew up in ‘orchestrated chaos’. Ruth was a fiercely protective woman, but her children knew nothing about her. In ‘The Colour of Water’ McBride tells the remarkable story of his mothers life; a rabbi’s daughter, born in Poland and raised in the Deep South who fled to Harlem, married a black preacher, founded a Baptist church and put twelve children through college. Interspersed throughout his mother’s compelling narrative, McBride shares recollections of his own experiences as a mixed race child of poverty.

A vivid portrait on race and identity, ‘The Colour of Water’ was a beautiful story of McBride growing up, and of his mother Ruth. The dual narrative between their stories was exceptionally done, starting with both Ruth and James as children, struggling with their identities in contrasting ways, and ending as the people they both came to be. Ruth and James could not have had more contrasting lives, however the thread that connects them, aside from being mother and son, was the search for identity and understanding;

‘It took many years to find out who she was, partly because I never knew who I was. It wasn’t so much a question of searching for myself as it was my own decision not to look. As a boy I was confused about issues of race but did not consider myself deprived or unhappy. As a young man I had no time or money or inclination to look beyond my own poverty to discover what identity was. Once I got out of high school and found I wasn’t in jail, I thought I was in the clear’ p.205 in ‘The Colour Of Water’

McBride explores mixed race identity with considerable nuance, as well as the tumultuous landscape of trying to understand his Jewish heritage too. He writes with candour as he recounts various times in his life when he was confronted and confused about who he was, what race meant and why his mother was steadfast on never discussing it;

‘Being mixed is like this tingling feeling you have in your nose just before you sneeze - you’re waiting for it to happen but it never does. [...] I felt frustrated to live in a world that considers the colour of your face as an immediate political statement whether you like it or not. It took years before I began to accept the fact that the nebulous ‘white man’s world’ wasn’t as free as it looked’ p.205 in ‘The Colour Of Water’

‘The Colour of Water’ was unbelievably moving. Ruth’s life was remarkable and the fact she raised twelve children with such heart despite everything she had been through was incredible to read. Ruth lived a hundred different lives and McBride’s evocative and flowing prose paints her as the brave and admirable woman she was. McBride’s approach to writing about both of their lives was exceptionally well done and I loved every single word of it. It was an outstanding tribute to his mother and the life she created for them.

In addition to the exploration of race, McBride wrote incredibly interesting meditations on religion. He comments on where race and religion intersect, and where other times diverge. McBride explores this through how he felt trying to understand his Jewish heritage, along with the dismissal his mother received in founding a church that was almost exclusively attended by the black community. McBride and his mother both visually stood out within the religious communities they identified with, subverting stereotypical expectations of where race and religion intersect.

‘The Colour of Water’ was an unbelievable story about a truly remarkable individual. This memoir was immediately engrossing and so easy to read. I would wholeheartedly recommend this and call it a total buy. After finishing I frantically started googling James McBride to try and find some photos of Ruth and to learn when she died. And to my great surprise (because I truly had not made the connection) James McBride is the author of the recently released book ‘The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store’ which I have been meaning to read! McBride has said that the fictional story is based on his grandparents, Ruth McBride’s parents, who were Jewish and ran a grocery store in a predominantly black neighbourhood. I cannot wait to read this with the knowledge I now have about Ruth and her family. If you have read ‘The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store’ I would recommend this memoir to learn all about where the inspiration of the book came from. If anyone has read this, please let me know!

‘River East, River West’ by Aube Rey Lescure follows two intergenerational stories searching for belonging while navigating the rapidly changing landscapes of modern China. The first is set in Shanghai in 2007, where fourteen-year-old Alva is convinced a better life awaits her in America and resents being raised in Shanghai by her American expat mother. When Alva’s mother announces her engagement to their wealthy Chinese landlord, Lu Fang, Alva’s hopes of leaving are crushed. She decides to plot for the next best thing; International American School in Shanghai. Upon admission, Alva is surprised to discover a more exclusive and seedier world that she imagined. The second narrative follows Lu Fung in the seaside city of Qingdao in 1985. He is a young man and a lowly clerk in a shipping yard. Though he aspires to a bright future, he is one of the many casualties of harsh political reform. When China opens its doors to the first wave of foreigners in decades, Lu Fang’s world is split wide open after he meets an American woman who makes him question what he should settle for.

‘River East, River West’ was a compelling exploration of the experience of being biracial and the struggle of understanding your identity. I thought Lescure did a great job of reimagining how you are impressed with things as a child through Alva’s perception of America. Through watching American films, Alva is obsessed with the ‘American Dream’ and is assured that her life would be full of more love, opportunities and fun if she was raised there.

Lescure was raised in Shanghai with an expat American mother, who attended an international school after finding Chinese public high school crushing and depressing. Lescure speaks to an assumption of transience within the expat community, with people only ever viewing Shanghai as a temporary place and never going to stay in China long term;

‘I wanted to write a book that was not just about expatriation and expats, but rather about the impact that that kind of flow of population has on Chinese characters or, you know, mixed-race Chinese characters’ Lescure in the ‘Books and Boba’ podcast8

Lescure said she wanted to write a book that spotlighted biracial children and how they were reacting to that infiltration of Western media, the physical presence of Westerners in their country and the shadow of imperialism. I think this is exactly what she achieved with Alva, exploring the tension that can exist between the contrast of being western and eastern dual nationality. American individualism is in direct conflict with the sentiments of nationhood and collectivism that prevail within Chinese society. This conflict is presented most directly with Alva’s contrasting experiences with public and private school.

Although Alva’s character had the most nuance when it comes to identity and belonging, I enjoyed Lu Fang’s narrative more. I thought the exploration of the Cultural Revolution on those who were on the cusp of adulthood was incredibly compelling. Lu Fang had his whole life ahead of him, and because of the Cultural Revolution, ended up leading a life he never expected and ultimately was never satisfied with. In that sense, Alva and Lu Fang both mirror each other with the sentiment that they feel unsatisfied with their lives in China. While reading Lu Fang’s narrative I was reminded of ‘Cocoon’ that also discussed the impact of the Cultural Revolution in China on those who lived through it.

‘River East, River West’ was easy to engage with and I enjoyed reading it. The novel ended up being more poignant than I expected it to be about cultural identity, familial love and what it means to belong. It explored aspects of regret and the shortcomings of the American dream through two alternative, but equally compelling, generational perspectives. I would call this a borrow. Since reading, it has been shortlisted for the Women’s Prize!

‘Chinatown’ by Thuân. Our narrator is riding the Metro when an unattended bag has been found. As it shudders to a halt, a fantastical interior monologue begins in her head. She looks back to her childhood in early 80s Hanoi, university studies in Leningrad and her life in France as an immigrant and single mother. But most of all she is thinking about Chinese-Vietnamese Thuy, whom she married in the aftermath of the Sino-Vietnamese war, much to her parents disapproval, and whom she has not seen for eleven years. The mystery around his disappearance feeds her memories, dreams and speculations in which the idea of Saigon’s Chinatown looms large in her mind.

Through a breathless monologue, the narrator of ‘Chinatown’ is attempting to face a past that haunts her. This stream of consciousness writing style is hard to follow at times but ultimately it works so well. The structure Thuân chose to write this story was exceptional, forcing us into the mind of the narrator as she recounts her experiences with identity and immigration. The translator's note describes Thuân’s writing style perfectly;

‘there was nothing to prepare the reader for pages upon pages of short, repetitive, choppy, loopy (and sometimes loony) sentences that draw them further and deeper into a maze of time, space, memories and harsh truths’ p.175 from the Translators Note in ‘Chinatown’

I can’t describe it any better than that.

Thuân writes a complex exploration of exile and discrimination as our protagonist has struggled most of her life with the issue of belonging. ‘Chinatown’ is a meditation on being an outsider. This sentiment begins with her relationship with Thuy which starts when they are at school, amidst the Sino-Vietnamese war in early 1979. This war deepened Vietnam’s hostility towards China, and the countries engaged in a series of intermittent and brutal wars for the next twelve years.9 This hostility would have been felt deeply within the population and led to extensive discrimination against anyone Chinese. This marks the beginning of a life for our narrator in isolation. She feels isolated by her family, Vietnamese society, Chinese society and subsequently French society. After moving to France, she experiences racism from fellow teachers. Everyone addresses her as ‘Madame Au’ which is Thuy’s Chinese last name, despite herself being Vietnamese, and having no connection to the Chinese French community. Our narrator is marginalised and disconnected from any kind of community, and this sentiment is further entrenched by the narrator being literally trapped in a train carriage while she recounts her story.

‘Chinatown’ sets out to demythologise and offer criticism on Western paradises, Orientalist romanticism, socialism, nationalism and the feats of globalisation.10 Thuân challenges what it means to be a citizen of the world where there is hostility around every corner. However, what dominates the narrative the most are the lingering questions about her former husband Thuy, revisiting their history together repeatedly in an attempt to gain some clarity. Our protagonist tells a sad story about displacement, immigration and longing for a place that doesn’t exist.

I will admit this was a challenge to read because it is not structured with any breaks. Despite ‘Chinatown’ making me work hard, I enjoyed how Thuân approached this and the writing was stylistically impressive. A remarkable approach to exploring the immigrant experience, especially Asian immigrants within the western world and how it feels to be subjected to discrimination with sentiments along the lines of ‘all Asians look the same’ from westerners. It explores the debilitating effects of migration and racism with a highly immersive approach. I would recommend ‘Chinatown’ and call it a borrow. It was a dense and demanding piece that is deeply compelling.

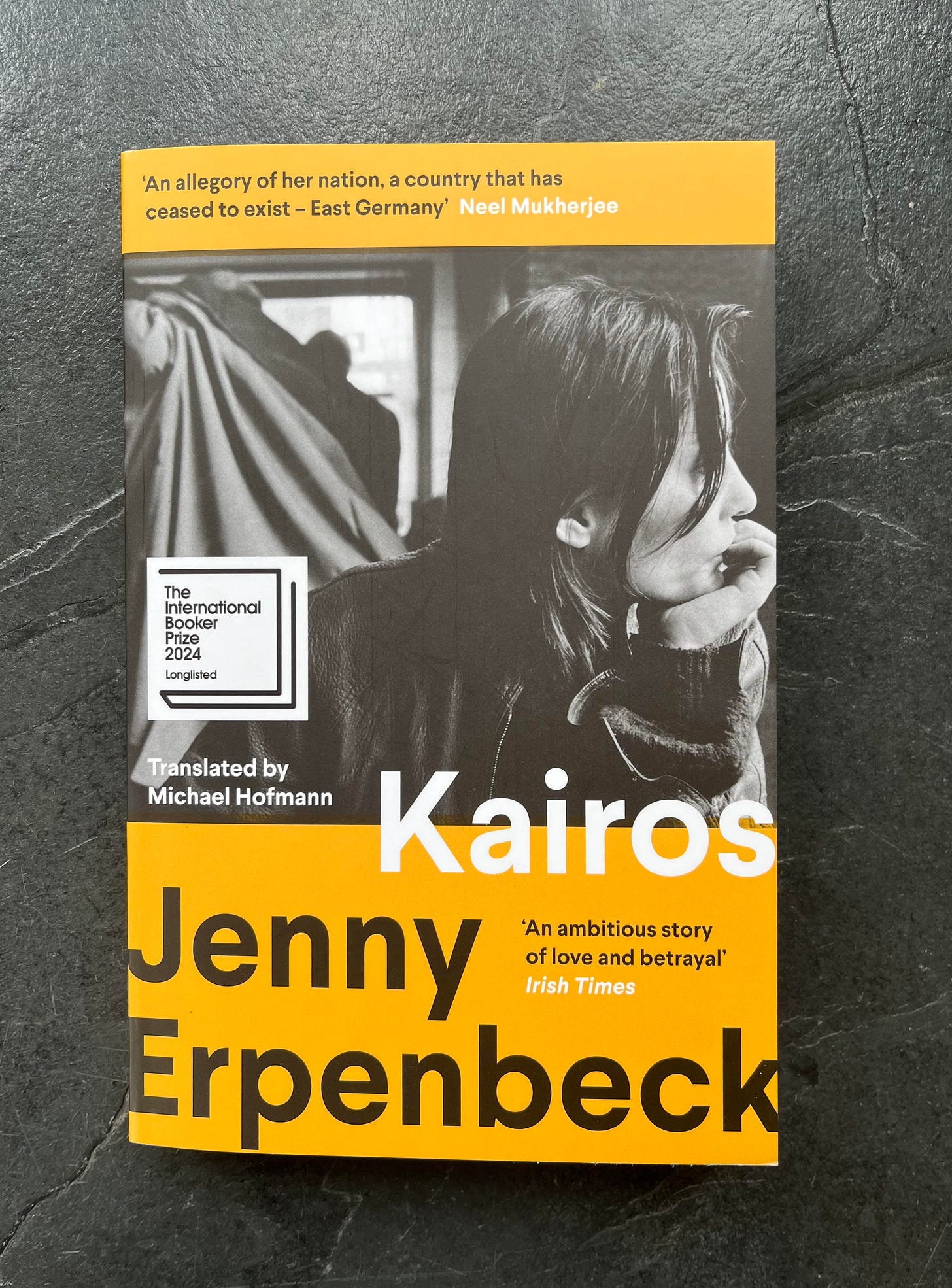

‘Kairos’ by Jenny Erpenbeck. A romance begins in East Berlin at the end of the 1980s when nineteen-year-old Katharina meets, by chance, a married writer in his fifties named Hans. There is an intense and sudden attraction, fuelled by a shared passion for music and art and heightened by the secrecy they must maintain. They fall in love and their long-running affair takes place against the background of the declining GDR, through the upheavals triggered by its dissolution in 1989. When she betrays him with a colleague, the relationship takes a darker turn, just as the GDR begins to crumble.

I read ‘Kairos’ because it was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize and it was not to my taste. ‘Kairos’ is Erpenbeck’s approach to an allegory about Germany. While I did not enjoy it, I appreciate what Erpenbeck is attempting to do. She is using the obscure, and incredibly concerning, relationship of Katharina and Hans to represent the state of Germany at the time and the relationship between the East and the West. The landscape is overflowing with shame and secrets as life in communist East Germany is represented by Katharina. The relationship between her and Hans becomes a tale of control, manipulation and guilt. I understand Erpenbeck is trying to communicate that the people living in East Germany were living under a sadistic and oppressive regime, unable to escape. Katharina represents this by accepting quite a significant level of abuse from Hans that we can assume, due to her adolescence, she interprets as love and affection.

Zadie Smith describes ‘Kairos’ as a ‘doomed romance’ and I just think that could not be further from the truth. ‘Kairos’ is a story of abuse that is being framed as deeply romantic. Reading about the power imbalance between this age gap relationship was not pleasant. Although I am aware that this is probably exactly what Erpenbeck intended with the relationship, I felt like it could have been approached completely differently. Despite my criticism of the ridiculous relationship, this is not the main reason why I didn’t enjoy reading. The structure and writing style was incredibly tedious and repetitive, making it (dare I say) boring to read. What I found most challenging within the narrative was the lack of political and historical context throughout the book. Because ‘Kairos’ is described as a literary fiction that discusses German politics and history, I expected this to be apparent throughout to contextualise how Hans and Katharina represented the turmoil within Germany from 1949-1990. Instead we are submerged into a dense and painful toxic relationship which is disturbing to read.

‘Kairos’ could have been so much more profound. The vehicle of using a relationship between two generations of Germany to represent the cultural and sociopolitical shift within the country is a great idea. Analysing the dynamic between two generations who experienced such drastically different countries has the opportunity to create such layered, subtle and ambitious writing. However, Erpenbeck took this metaphor and cheapened it by writing about an abusive and horrendous age gap relationship that took away from the nuanced discussion around Germany that I think she intended. I wouldn’t recommend this to a friend and therefore I won’t recommend this to you. This was a bust. If I hadn’t set myself the challenge of reading the entire shortlist, I probably wouldn’t have even bothered to finish this - but how can I call myself a book reviewer if I don’t do you the service of reading the bad ones too.

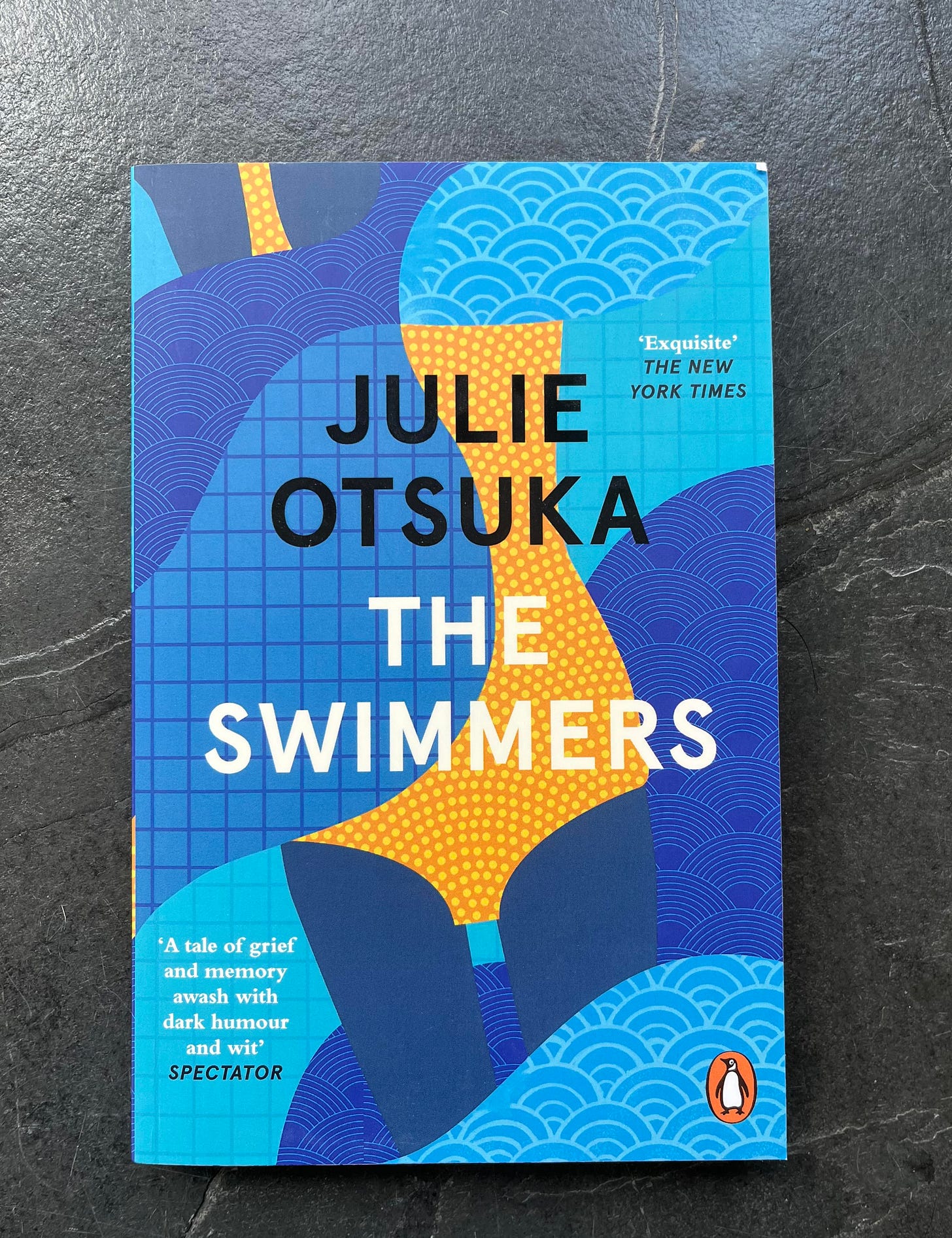

‘The Swimmers’ by Julie Otsuka. The Swimmers are unknown to one another except through their private routines at the pool. It is a heaven of unexpected kinship and private solace. For Alice, her daily laps have become a ritual that gives her life meaning, even though she doesn’t remember much. One day a crack appears deep beneath the surface of the water, and then another, and another. The pool is forced to close for repairs, and with that Alice is plunged into dislocation and chaos. Away from the steady routines of her swimming, she is engulfed by difficult memories of her own past. As her sense of home and self slip further out of her grasp, her daughter must navigate the newly fractured landscape of their relationship.

‘The Swimmers’ was a really beautiful exploration of ageing, memory loss and death. It gracefully discusses the inevitability of illness, disability and the loss of self in old age. Otsuka writes a sad but humorous meditation on dementia and the impact it can have on those around you. The first half of the novel focuses on the beauty in the mundane routines we establish and rely on. We are taken into the world of the swimmers at the pool and how the act of swimming creates a strong sense of belonging to those who are in desperate need of routine to help deal with tragedy. Stylistically ambitious, Otsuka writes in flowing second person to put you in the perspectives of different characters. The act of swimming allows Alice to retain parts of her former life even as her memory starts to slip away. The cracks that show on the pool floor serve as a metaphor for the state of Alice’s memory as her dementia progresses. The more cracks that appear, the more she begins to lose herself and her identity.

In the second half of the novella we are put in the perspective of Alice’s daughter as she watches Alice’s cognitive and physical deterioration. Alice’s daughter struggles with feelings of loss and sorrow surrounding her mothers illness, and berates herself for all the ways she feels she has failed her mother. However, she is also washed with a love about the life her mother has lived. Where ‘The Swimmers’ could be melancholic, Otsuka instead finds the beauty in the seemingly unextraordinary lives that most people lead. Otsuka writes a sweet exploration of mortality and what it means to live, poetically insinuating that to die means you had the gift of living. To balance the grief Otsuka writes in good humour on the experience of putting someone in a home, and how expensive they are.

‘The Swimmers’ was inspired by Otsuka’s own experience with her mothers dementia diagnosis. Otsuka was faced with remnants of her mother’s life she found in boxes as she tried to decipher who she was. Otsuka said she was fascinated by how unknowable people are and wanted to write about what it feels like to lose your mind. Otsuka was inspired by her mothers story, which juxtaposed such ordinary details against such large events of human history.11

Alice’s final words were ‘It’s a good thing there’s birds’ I couldn’t agree more.12 I can only hope last words will be as poetic and profound. A book focused around dementia is always going to be difficult for some, but I think Otsuka approached the discussion around the illness elegantly. Reading ‘The Swimmers’ made me think back to ‘Intervals’ by Marianne Brooker from last month and the frank nature that both books discuss illness and death. Both approach death with warmth because life is a beautiful thing and death is just a part of it. I really enjoyed ‘The Swimmers’ with its gentle and funny approach to health decline. I would recommend this book and call it a buy! I was grateful to not be ending the month on the sour note of ‘Kairos’.

And that concludes my April Reads! My favourite reads this month were ‘Abyss’ and ‘The Colour of Water’. Both of them were such a joy to read in very different ways.

My first read of May is ‘Cantoras’ by Carolina De Robertis. This book has been on my shelf for a while and I picked it up because I realised, to my horror, that I haven’t read a queer book for a hot minute! If anyone has read this, please let me know what you thought in the comments.

International Booker Prize Shortlist

As we all know, because I committed to it in writing last month, I am reading the International Booker Prize Shortlist. I have read five out of the six, with just ‘Mater 2-10’ by Hwang Sok-yong to go, so I am almost done. Here are my thoughts:

Unless ‘Mater 2-10’ changes my life, I think ‘Crooked Plow’ by Itamar Vieira Junior should win. I loved ‘The Details’ by Ia Genberg so much, but I think ‘Crooked Plow’ is a more impressive novel and work of translation.

The judges described the list as ‘books that speak of courage and kindness, of the vital importance of community and of the effects of standing up to tyranny’ and I think ‘Crooked Plow’ is the embodiment of this quote. The prize argues that they are an ‘invitation to immerse themselves in a perspective so different from their own’. ‘Crooked Plow’ is the story of a neglected and marginalised community that discusses the persistent effects of racism and colonialism. These rural communities are still living in conditions similar to their ancestors who were enslaved. Itamar Vieira Junior writes an exceptional meditation on the importance of place and community for those who did not have a say in their destination.

‘Crooked Plow’ highlights a collective of people who are forgotten within their own country and across the world. Itamar Vieira Junior and translator, Johnny Lorenz, both do a remarkable job of transporting the reader into a culture and way of life that is hidden from our viewpoint. It was a beautiful book to read and an exceptional demonstration of the power of reading translated literature. Read my full review of ‘Crooked Plow’ here. And this goes without saying, but if you haven’t read ‘Crooked Plow’, may I strongly recommend you do.

☞ At the end of the day, prize lists are just a bit of fun. I have read so many translated books in the last year that deserve more attention and accolades than most the books on this list - but that’s just my opinion.

☞ I still look forward to reading ‘Mater 2-10’ next month to see how the shortlist presents overall.

☞ No disrespect to the International Booker Prize Judges but I think Martha’s Monthly has better translated taste x

Let me know your thoughts:

❀ What have you read and enjoyed in April?

✮ Have you read any of these books? What did you think?

✿ Has anyone read any of the books off the International Booker Prize list? Do you agree or disagree with me?

❊ Do you have a book recommendation for me based on the theme of this month? What books have to read that speak to the sentiment of belonging?

Thank you, as always, for reading. I hope you found a book you’d like to read!

I am deeply grateful for all the comments on last months newsletter. I always look forward to engaging with you all, and hearing about what you are reading and thinking - so please never stop telling me. ♥︎

I’m going to look into how to order friendship bracelets (or friendship bookmarks?!) for 596 people.

See you next month,

Happy Reading! Love Martha x

If you know someone who is always in search of books to read, share this newsletter with them!

Catch up on what you might have missed:

And before you go - if you enjoyed this, why not subscribe? <3

https://www.shondaland.com/inspire/books/a43378467/eleanor-catton-birnam-wood/ - quote obtained from this article

Quote obtained from this interview - if you have read the book, this whole interview is very interesting, I’d recommend!

Quote from the interview above ^^^

And still to this day!!! It is still an enormous issue for the black community. This is absolutely not exclusive to this time period, so please do not take my use of the past tense to discuss institutionalised racism in relation to ‘If Beale Street Could Talk’ to suggest I do not believe it still exists.

https://www.transparency.org/en/countries/angola - the index link for anyone who wants to look

https://databankfiles.worldbank.org/public/ddpext_download/poverty/987B9C90-CB9F-4D93-AE8C-750588BF00QA/current/Global_POVEQ_AGO.pdf - Poverty & Equity brief on life in Angola

I am aware this was written by an American author so colour is spelt ‘color’. However, as someone from the UK I just cannot write colour like that. It feels so wrong. So I will writing ‘The Color of Water’ as ‘The Colour of Water’. I hope you can all understand and support this grammatical decision.

https://booksandboba.com/2024/01/27/256-author-chat-w-aube-rey-lescure/

https://www.hoover.org/research/1979-sino-vietnamese-war-and-its-consequences

The line ‘‘Chinatown’ sets out to demythologise and offer criticism on Western paradises, Orientalist romanticism, socialism, nationalism, post-communism and the feats of globalisation’ is inspired/partially quoted from the Translators Note on page 178 in ‘Chinatown’.

https://lithub.com/julie-otsuka-on-writing-from-and-into-memories/ - Otsuka discusses the inspirations for ‘The Swimmers’ in this interview.

Line found on p.168 of ‘The Swimmers’

I so enjoy your reviews. More thoughtful discussion….more to read. Thank you

I loved The Details too!! Also, hear you on the UK / USA ´color’ and ‘colour’ discourse and I offer you ‘maths’ and ‘MATH’ 😂