February Reads

Family, legacy and generational trauma + my classic novel reading goal for 2024

Welcome to Martha’s Monthly, February Reads edition! In February, almost all the books I read had themes of family, legacy and generational trauma. This was a complete accident but I admire my subconscious desire to create a monthly theme.

My February reads included authors from China, Ireland, Poland, Norway (twice!), Barbados and Palestine. To see the translated reads from February on Martha’s Map, click here.

For those who are new, buy, borrow, bust is my recommendation key. Buy = I immensely enjoyed and heavily recommend this book. Borrow = I think this book is still well worth a read and I’m glad I read it. Bust = I wouldn’t recommend this book from my own reading experience.

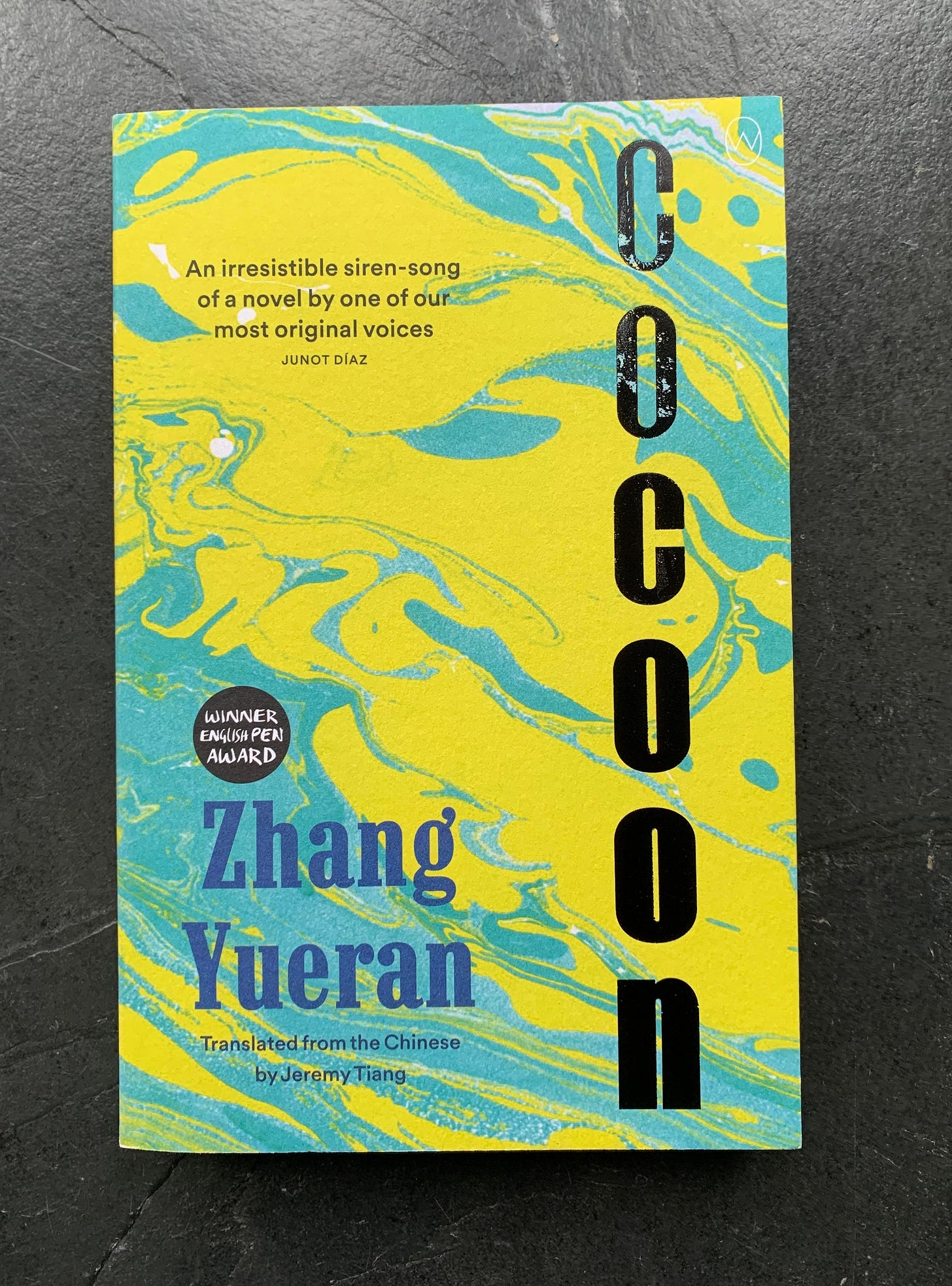

‘Cocoon’ by Zhang Yueran is the story of a new generation coming to terms with China’s past. Cheng Gong and Li Jiaqi were childhood friends and grew up together in a Chinese provincial capital in the 1980s. Many years later they have reunited and discovered how much they still have in common. Cheng Gong and Li Jiaqi are both determined to find out more about their grandparents' generation and a mystery from The Cultural Revolution which connects their families. Through an alternating narrative we revisit Cheng Gong and Li Jiaqi’s childhoods and learn about The Cultural Revolution from the perspective of the next generation. ‘Cocoon’ is a complex and thoughtful novel about hope, memory and generational trauma.

The Cultural Revolution was a decade long period of political and social chaos caused by Mao Zedong’s bid to use the Chinese masses to reassert his control over the Communist Party. It began May 1966 when party chiefs warned that the party had been infiltrated by counter revolutionists who were plotting to create a ‘dictatorship of the bourgeois’. A fortnight later, the party’s official mouthpiece newspaper urged the masses to ‘clear away the evil habits of old society’ by launching an all out assault. By August 1966 the mayhem was in full swing as Moa’s allies urged the Red Guards to destroy the ‘four olds’ - old ideas, old customs, old habits and old culture. The worst affected regions reported mass killings, cannibalism and torture. 1 The sheer complexity and brutality of The Cultural Revolution is something historians struggle to make sense of to this day. These themes of confusion, complexity and brutality are all explored in ‘Cocoon’.

‘Cocoon’ is a devastating novel in so many ways. It uniquely explores the collective trauma from The Cultural Revolution that exists within Chinese society through the eyes of two children. As Cheng Gong and Li Jiaqi recount the socioeconomic experiences of their childhood and dysfunctional family dynamics, we are given an insight into the behaviours of the adults surrounding them. As children, Cheng Gong and Li Jiaqi do not understand the fear and trauma that some members of their families are exhibiting. They interpret it as hatred and neglect towards themselves specifically, and therefore both struggle in different, but equally challenging ways. As a reader we can see that the behaviour of the adults around them is because they are traumatised from what has happened. Class, social status and economic standing are aspects of society that children often misunderstand or misinterpret. Therefore, Yueran exploring The Cultural Revolution through the perspective of children is incredibly unique. The mystery that connected Cheng Gong and Li Jiaqi’s families was unsuspecting and I didn’t see it coming. And in good faith of keeping it a mystery, I will not comment any further.

The violence and suffering that existed throughout The Cultural Revolution is never explicitly discussed within ‘Cocoon’; it is alluded to and we can tell the impact that the brutality of this time period had on the adults through their paranoia. As a reader you feel heartbroken for the childhoods of both Cheng Gong and Li Jiaqi as they both, at the time, had no perception that the behaviour of their parents and grandparents were not a reflection of them. Through their perspective we are taken on a journey of the societal aftermath of The Cultural Revolution. Cheng Gong and Li Jiaqi give us insight into collective societal PTSD that occurs after such horrific political violence. Can a generation that experiences something like that ever move on? And how does it affect the generations that come after?

‘Cocoon’ is a compelling novel full of bleak, nostalgic and poetic prose. I expected something slightly more overt about The Cultural Revolution going into reading this, but enjoyed the more subtle and quiet commentary nonetheless. I always think seeing cultural and political events through the lens of children is exceptionally clever and thought provoking. It offers valuable insight into the events that shape countries and subsequently future generations. I gained a wealth of knowledge about the social, societal and emotional impact of the The Cultural Revolution and relished in the thought provoking nature of the novel. I would call ‘Cocoon’ a buy. By exploring the complexities of human relationships and the power of hope in the face of tragedy, ‘Cocoon’ is a reflective and tense exploration of China’s past.

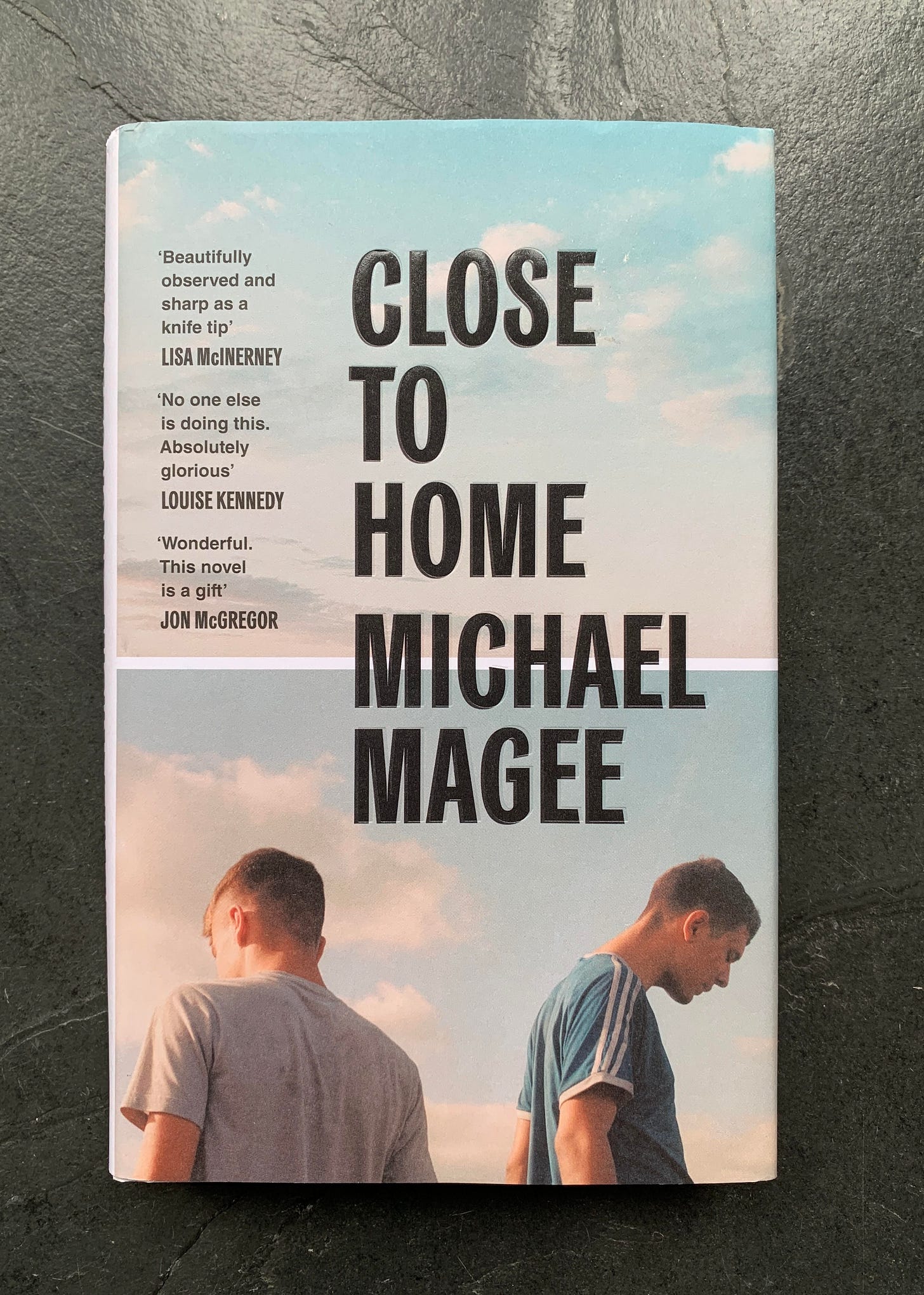

‘Close To Home’ by Michael Magee explores a complex portrait of modern masculinity, class and trauma. Set in Belfast in the early 2010s, Sean returns home after University to find his brothers drinking is worse than ever, that the jobs in Belfast have vanished and his degree isn’t worth the paper it's written on. He falls back into a routine with his friends from home who are stuck in a cycle of substance abuse and poverty. With his single mum living on the breadline, and no one to turn to, Sean loses control one night at a party and assaults a stranger. ‘Close To Home’ follows the aftermath of this event, as Sean attempts to make sense of who he has become. Magee writes about contemporary masculinity shaped by place and class, by individual and collective trauma, the intimacies of male friendship and the painful sensation of no longer belonging among the people you grew up with.

‘Close To Home’ was an absolutely beautiful and deeply compelling story. The story depicts a man among a network of lives being shaped by poverty, addiction and violence. Sean’s assault disrupts his life, as he quickly realises it's either sink or swim. We are submerged into this intersection of violence, masculinity and trauma that overhangs a generation of young people in Northern Ireland. Sean is gasping for air and often feels like he’s drowning, with no ability to control the next day, let alone his future. While Sean is trying to navigate his life, we gain insight into the lives of the adults around him and the cycle of poverty and cultural trauma is perpetuated by Sean’s Mum and Brother, Anthony.

Anthony represents the generational cycles of poverty and crime which keep young working-class men in harm's way and the enormous struggle to break free from them. The novel also holds a subtle but consistent nod to The Troubles and the psychological impact this had on the previous generation. Just like in ‘Cocoon’, we are witnessing the generational psychological aftermath of experiencing that kind of violence. Sean’s Mum demonstrates the long-lasting psychological scars the communities of Northern Ireland were left with after The Troubles. A 2011 study found that Northern Ireland has the highest recorded rate of PTSD of any studied country in the world and has the highest suicided rate in the UK. 2 This collective trauma bleeds through the page. They are stifled by so many aspects of their life which are outside of their control. This complete lack of control is what leads Sean to assaulting someone, relying on violence in a way he has seen surround him his whole life. Magee discusses this in his LA Times interview on Sean’s relationship to violence;

‘Violence manifests itself in different ways in different contexts but underneath that there’s always a person. That’s not to say that there aren’t sociopaths in the world, but I always think that people are the product of external forces. Class, gender, race, or poverty don’t make a person, but it moulds them. He’s grown up in a world where the mode of resolving conflict is to resort to violence. But he’s also performing.’ - Magee 3

Alongside this deeply vivid and accurate exploration of trauma caused by The Troubles, I would also argue ‘Close To Home’ deeply links to the wider cultural lens of today. Sean is experiencing a cost of living and housing crisis, unable to find work and struggling to have any agency over his life. This socioeconomic stance of the novel is incredibly accurate to today. No one has any money and life is, almost in every aspect, hard. Sean is experiencing this in a more severe way due to the chronic poverty cycle that exists for some people that they just can’t get out of. It’s generational and is incredibly hard to break. It is rare to find nuanced financial commentary within fiction. More often than not, money is not mentioned.

‘Close To Home’ is a beautifully observed and sharp novel. It is incredibly easy to read, tender and engrossing. I can’t believe this was Magee’s debut and am very excited to see what he does next. He is a truly gifted writer. It reminded me a lot of ‘Trainspotting’ and both of Douglas Stuart’s novels ‘Shuggie Bain’ and ‘Young Mungo’, exploring societies permeated by trauma and hopelessness and how young people cope (or don’t) growing up in such an atmosphere. I loved this so much and flew through it. ‘Close To Home’ is an absolute buy and I recommend it wholeheartedly. This book was wonderful.

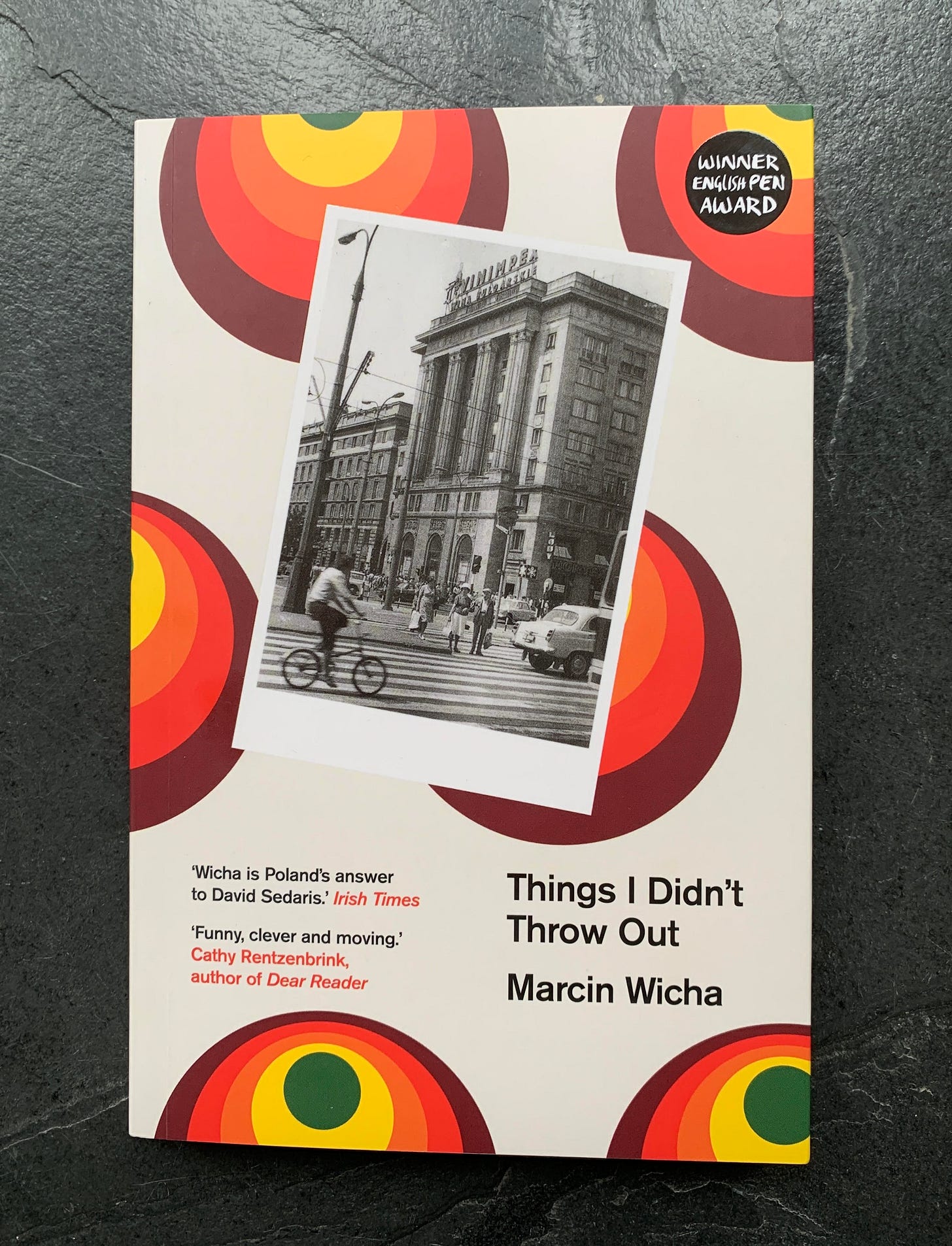

‘Things I Didn’t Throw Out’ by Marcin Wicha is an intimate, unconventional and funny memoir about everything we leave behind. When Marcin Wicha’s Mother, Joanna, dies and leaves her apartment intact, Wicha is left to sort through her things. Through her everyday objects he begins to construct an image of Joanna as a Jewish woman, a mother and a citizen. As Poland emerged from the Second World War into the material meanness of the Communist regime, shortages of every kind shaped its people in profound ways. What they chose to buy, keep, and arguably hoard, tells the story of contemporary Poland. The objects that scattered, and cluttered, Joanna’s home all accumulate into portraits of a woman, and ultimately her country.

‘We won’t disappear without a trace. And even when we do disappear, our things remain, dusty barricades' - p10 in ‘Things I Didn’t Throw Out’

This memoir was unlike one I have ever read before, exploring an alternative side of death to those who are responsible for clearing out the homes of the deceased. Wicha remembers his mum through the objects she left behind in a satirical and funny way. Why do we buy the things that we do? What significance do we bestow upon them? I thought the way Wicha used his mothers objects to represent the socio political landscape of the time was fascinating. He discusses the material impact of communism, such as the printing shortages, that made something like books so valuable to his parents. Or the shortages of food that were experienced in Poland from the 1940s all the way to the 1980s, when rationing was abolished in 1989. This resulted in his mother hoarding certain foods, unused. For example, Joanna was gifted some American sugar in the 1940s and she never opened it. Wicha tastes it and reveals the sugar tastes ordinary. What was she saving it for? Wicha also finds ‘The Stalin Cookbook’, owned by his grandparents. The USSR was characterised by famine, therefore this cookery book is an erratum. You must believe the illustrations but ignore the evidence. You can eat the pictures, but no one actually cooks from it. 4 This was such an interesting window in time. Communist regimes are so often discussed in political, economic and social theory, but rarely explored using the prism of an object from the time.

The objects that scatter Joanna’s home remind Wicha of the type of Jewish Woman she was and the relationship she had to her identity in Post War Poland. The population of Jews in Poland, which formed the largest Jewish community in pre-war Europe at about 3.3 million people, was all but destroyed in 1945. 5 Wicha recounts the complex relationship his mother had with being Jewish. How she was proud and fearful all at the same time. And how she navigated her Jewishness inside and outside her home.

This memoir was thought provoking in lots of ways about the attachment we have to objects, what they come to represent to certain people, and how the objects we buy will outlive us when we die. Our relationship to consumption in relation to beyond our own lives is something (I think) we all fail to consider. To Wicha’s parents, who lived under communism and scarcity, it is understandable and conceivable as to why they would hoard certain objects out of fear of them disappearing, such as sugar and paper. Wicha’s parents do not have the scale of consumption that many people of our generation would have when we die.

This really made me think about what I own and consider what will outlive me. What bit of plastic will have a longer lifespan than me? Technically - all plastic. It feels eerie in a capitalistic overconsumption way. Overconsumption is so rife in our society today, thinking about the position that our children or relatives might be in, having to clear out our homes, is nauseating. But not because we would be dead, but because of the amount of crap that we might accumulate under our roofs. Perhaps the new push for more conscious consumerism should be; What will your child do with your Stanley Cup when you die? Or your slave laboured plastic top from Boohoo or Zara? 6 Or the excessive amount of books you own? (this last one is aimed directly at me.)

Overall I enjoyed this novel more because of the thought provoking nature, rather than the actual content. It doesn’t read like a story, but rather fragmented vignettes and anecdotes that are sparked by certain objects. I understand why Wicha approached it this way, and think this was probably the best narrative structure for it. However after gleaning such insight into Joanna’s life through her miscellaneous objects, I wanted to know more about her. And for that reason I wanted more storytelling and less anecdotal writing. For me, ‘Things I Didn’t Throw Out’ is a borrow. It was a really interesting and unique take on the memoir genre and I enjoyed reflecting on consumption and learning about how objects can come to represent turbulent eras, such as Communism.

‘A Shining’ by Jon Fosse. As someone who views themselves as a bit of a self proclaimed, high brow literature reader (otherwise known as a book snob) I am always interested in The Nobel Prize for Literature. In 2023, Jon Fosse won this prize. I had heard of him before, but I hadn’t ever read any of his work. So I picked up ‘A Shining’ as a starting point into his proclaimed innovative prose. This book is only 48 pages but god is there a lot to say about this.

This novella is about a man. He starts driving without knowing where he is going. He alternates between turning right and left, until he gets stuck at the end of a forest road. Soon it gets dark and starts to snow. But instead of going back to find help, he ventures into the dark forest. Inevitably, he gets lost, and as he grows cold and tired, he encounters a glowing being amid the obscurity; strange, haunting and dreamlike.

‘A Shining’ is so ambiguous you could take many different interpretations from it, but for me it reads like a fever dream about the spiritual transition from life to death. Fosse subverts the expectations you have for a book and this was the most interesting and bizarre piece of writing I have read in a while. It operates as a flowing stream of conscious prose from someone who seems to be losing their mind, or their life. Fosse starts with a tedious and monotonous tone, which is actually quite painful, but it grows into an introspective and thought provoking piece about life and death. The man is walking the tightrope between the two worlds of life and death, swaying with immersion as he describes the cold, white forest. I interpreted ‘A Shining’ as the spiritual journey of the mind between transitioning from living in a physical body to the wider ether.

Fosse is probing the limits of the perception, writing about what is ‘unsayable’. This novella is evocative, strange and deeply reflective as it tackles themes of death and confusion with a philosophical undertone. I wouldn’t recommend this book to everyone. If you read for enjoyment or ease, this isn’t the book for you. But if you are looking to challenge your relationship with writing and reading, I would suggest you give this a go. It is hard to recommend a book where so much of the experience of reading takes place once you’ve put the book down. Of course all great books should, and do, make you think after you’ve read it. But ‘A Shining’ was something totally different. This writing transcends the page, it’s about how it makes you feel after. There is not much of a story here, but more a window to make you think. Because it is more about the after rather than the during, I’d call ‘A Shining’ a borrow. From only 48 pages of his work, Fosse deserved that prize. He really is pushing the boundaries of literature. I’m very intrigued by what his other work is like.

‘The Island of Forgetting’ by Jasmine Sealy. For those of you who were here for my October Reads you may remember that I had a book advent calendar. It was as much fun as you’d suspect and I was able to choose four books (without knowing the title or author). It was a variation of a blind date with a book, and this was one of my picks! Spanning fifty years, ‘The Island of Forgetting’ passes through four generations of one family living on the island of Barbados. There is Iapetus, a lonely soul haunted by the memory of his father; his son Atlas, dreaming of a life far removed from his reality; Atlas’s daughter Calypso, struggling to find her place in an unforgiving society; and her son Nautilus, grappling with various parts of his complex identity. Each generation longs to escape their circumstances but find themselves trapped by a hidden history. With every passing decade, each generation contends the question: how can the things we don’t know define our futures?

Set against the vivid backdrop of Barbados from 1962 to 2019, ‘The Island of Forgetting’ explores the complexities of family and trauma, and the impact this has on personal identity. I was drawn to this book because of the generational lens. I enjoy a story that explores themes that transcend generations, allowing us to understand how a character has been shaped by their past, parents and family. All four generations of this family share an obsession with leaving the island as they struggle to understand who they are. On the surface, this book is a tragic tale of a family who feel they don’t belong. This generational grapple with identity was incredibly compelling, witnessing one after the other feel that they are outcasts, unaware that their parents felt the exact same way. Underneath this family narrative, there is a slightly more thought provoking dialogue about Caribbean natives and tourism; the colonial legacy. The family owns a hotel business and they are trapped between serving others and empowering themselves. The relationship that the native islanders have with this tourist economy; what it’s like to live in a tourist destination and the impact this has on the islanders.

Throughout Atlas’s lifetime, the island changes in inconceivable ways, and witnessing this change was one of my favourite aspects of the story - you are sensing the socioeconomic landscape change in a way that is detrimental to them and their home. While I was reading this, I was reflecting back to ‘How To Say Babylon’ which I read last month and the parallels both books have when discussing the impact of colonialism and tourism on Island life.

Sealy masterfully uses this family to explore the multitude of experiences of prejudice, injustice and harm that afflict black families. Over just a brief time period of 50 years we are given insight into the sheer amount of abuse they suffer; racism, police brutality, colonialism and exploitation. Sealy creates an understanding of how these themes are cyclical, plaguing the family for generations. This shame and trauma is shown to impact the family in a tragic way. It is a realistic portrayal of the shadow of the colonial legacy and trauma many Caribbean islanders live under. The story argues how we are shaped by the things that happen before we are born. For so much of black history, many people do not know their own history, and Sealy explores this struggle for identity within each passing generation.

In many ways I felt that the generational exploration could have been richer, and I would have loved more of an insight on our initial patriarch Iapetus. Minor criticisms aside, ‘The Island of Forgetting’ was incredibly easy to read and engage with. It was enjoyable and I felt invested in the trajectory of the family. Sealy tackled enormous themes with elegance and empathy. I would call ‘The Island of Forgetting’ a borrow. I think a lot of people would really enjoy this book.

‘Will and Testament’ by Vigdis Hjorth is a story of generational trauma and complex family dynamics. Four siblings, two summer houses and one terrible secret. When a dispute about her parents will grows bitter, our protagonist Bergljot is drawn back into the family she cut herself off from twenty years before. Her mother and father have decided to leave two island summer houses to her sisters, disinheriting the two eldest siblings from the most meaningful part of the estate. To outsiders, it could be seen as a quarrel about property and favouritism. However, Bergljot has borne a horrible secret since childhood, and understands the gesture as something very different; a family attempt to suppress the truth. ‘Will and Testament’ is a lyrical meditation on trauma and memory, as well as a furious account of a woman’s struggle to survive and be believed. The writing is a hypnotic exploration of complex mistrust and misunderstanding.

This book was absolutely sensational and I was hooked from the beginning. Hjorth has done the most exceptional job of exploring trauma. ‘Will and Testament’ is a testament to how personal trauma is and how exceptionally difficult it can be, especially when caught up within a complex family dynamic. Bergljot demonstrates the suffocating impact trauma can have on your life, seeping into every crevice of your life; but to an outsider looking in it is difficult to detect. Hjorth takes us inside Bergljot’s mind as she experiences being gaslighted by her own family. The experience of reading is nauseating and fascinating as we revisit time and again the events of Bergljot’s past which haut her life. The more we come to understand the dynamic between Bergljot, her siblings, and her parents, the more is revealed about her past. The writing is poetic, gripping and beautiful. Bergljot’s story is sad and empowering in equal measure. A really accurate exploration of trauma to its core; how it stays with you and shapes your mind, life, body and relationships.

‘Will and Testament’ is unsettling and beautifully constructed. I devoured this story and have not been able to stop thinking about it since I finished it. This novel centres heavily on psychoanalysis, examining why her parents behave the way they do, examining the nature of abuse and what might motivate abusers to do what they did. I adore talking about a scenario from 50 different angles with my friends, revisiting different iterations of why certain things happen between certain people, so this style of novel was like crack to me. I loved the approach Hjorth took to exploring and communicating what happened. It is a stylistic choice some may find exhausting, but I loved it. I have no notes on Hjorth’s writing approach to this novel. ‘Will and Testament’ is a complete buy for me. I recommend it wholeheartedly.

‘Beloved’ by Toni Morrison. I read ‘Sula’ last year, and have had ‘Beloved’ on my shelf for a while, but not gravitated towards it. The gravitation I felt this month, aside from picking it up on Toni’s birthday, can be credited to

who has created a goal to read a classic novel a month for 2024. I saw Joel’s goal (linked here), admired it, and then looked to my own shelves only to be swiftly reminded of the amount of unread classics I own. I buy them with the good and honest intention of reading them, but because their acclaim and significance never wavers, I often pass them by for shiny newer titles. This pattern of behaviour has resulted in many classics collecting dust on my shelf. So - I have been inspired by Joel, albeit one month late, to follow a classic novel reading goal myself for 2024; one classic novel a month. More about what books this may entail at the end of this newsletter. For now, let's start with ‘Beloved’.Terrible, unspeakable things happened to Sethe at Sweet Home, the farm where she was born and lived a slave. Eighteen years later she escapes to Ohio, but she is still not free. Sethe’s new home, 124, where she lives with her daughter Denver, is haunted. Not only haunted by the memories of her past, but also by the ghost of her baby, who died nameless and whose tombstone is engraved with a single word; ‘Beloved’. Sethe works at keeping the past at bay, but it makes itself heard in the lives of those around her. After former slave from Sweet Home, Paul D, arrives at 124 and exorcises the ghost, a mysterious teenage girl arrives calling herself Beloved. And Sethe’s past explodes into the present.

‘Beloved’ is a horror that is so deeply unsettling to read because it is plausible. It’s real, it happened and it is representative of the cruelty that goes unmentioned in American history. The horror in this novel is rooted in the torture and abuse that fellow human beings carried out on each other. The story subverts expectations because the horror is not the ghost that haunts the house, as every other horror story would perpetuate. Instead it is what we know to be true, what humanity is capable of, what was an acceptable way to treat people for hundreds of years. The horror is everywhere, and nowhere, because Sethe, Paul D and Baby Suggs are free. So what is there for them to fear? The characters of this story live simultaneously in the past and the present. Morrison forces us to reckon with the discomfort of the past and try to deeply understand that the trauma of the enslaved stays with them - that being free physically doesn’t mean they are free. ‘Beloved’ is a story rooted in the psychological horror and brutal dehumanisation of those who were enslaved.

Sethe’s character represents black womanhood during enslavement. Sethe represents the universal experience of female slaves; the wealth that you give slave owners through your ability to have children and the milk they can steal from you; ultimately treated like cattle.

‘For a used-to-be-slave woman to love anything that much was dangerous, especially if it was her children she had settled on to love. The best thing, he knew, was to love just a little bit; everything, just a little bit, so when they broke its back, or shoved it in a croaker sack, well maybe you’d have a little love left over for the next one.’ - Beloved p.54

Within ‘Beloved’ everything from plot to characterisation is fraught with political implication. It is really ambitious and a fundamental text on American slavery and its generational violence. ‘Beloved’ is full of history that feels inconceivable and too outrageous to be true. Morrison sets out to convey how entrenched racism and violence were towards the black community in all aspects of the story. ‘Beloved’ includes ‘good’ white people, but Morrison makes sure as a reader you never get too comfortable with who you think is ‘good’ or ‘bad’. She explores how entrenched the attitudes were in 1870s America, reminding you that ‘good’ white people were still taking part in the system that made black people second class citizens. My favourite part of the whole story was this excerpt after Denver leaves a house of ‘good whitefolks’;

‘Denver left, but not before she had seen, sitting on a shelf by the back door, a blackboy’s mouth full of money. His head was thrown back farther than a head could go, his hands were shoved in his pockets. Bulging like moons, two eyes were all the face he had above the gaping red mouth. His hair was a cluster of raised, widely spaced dots made of nail heads. And he was on his knees. His mouth, wide as a cup, held the coins needed to pay for a delivery or some other small service, but could just as well have held buttons, pins or crab-apple jelly. Painted across the pedestal he knelt on were the words ‘At Yo Service’ - Beloved p.300

Morrison’s writing is so tense and compelling, like nothing I have ever read before. The way Morrison approaches memory and trauma is mesmerising, jumping from past to present so seamlessly. ‘Beloved’ is full of aspects of the Southern Gothic genre, a literary genre that focuses on the grotesque features of racism, violence and poverty. Sethe is a deeply flawed, disturbing and eccentric character. Yet we understand as a reader that the characteristics she's been attributed by those around her are not a reflection of her, but instead of the trauma of what's happened to her. In many ways I am finding ‘Beloved’ hard to write about as I just don’t think anything I say does the writing justice. This story was exceptional and I am certain I will never forget it. A total masterpiece.

I would call ‘Beloved’, without a doubt, a buy. I recommend it entirely but would not recommend reading it before bed. I felt so haunted by this book and I read, perhaps the ultimate scene of the story, just before falling asleep and let me just say I did not sleep well. I also loved

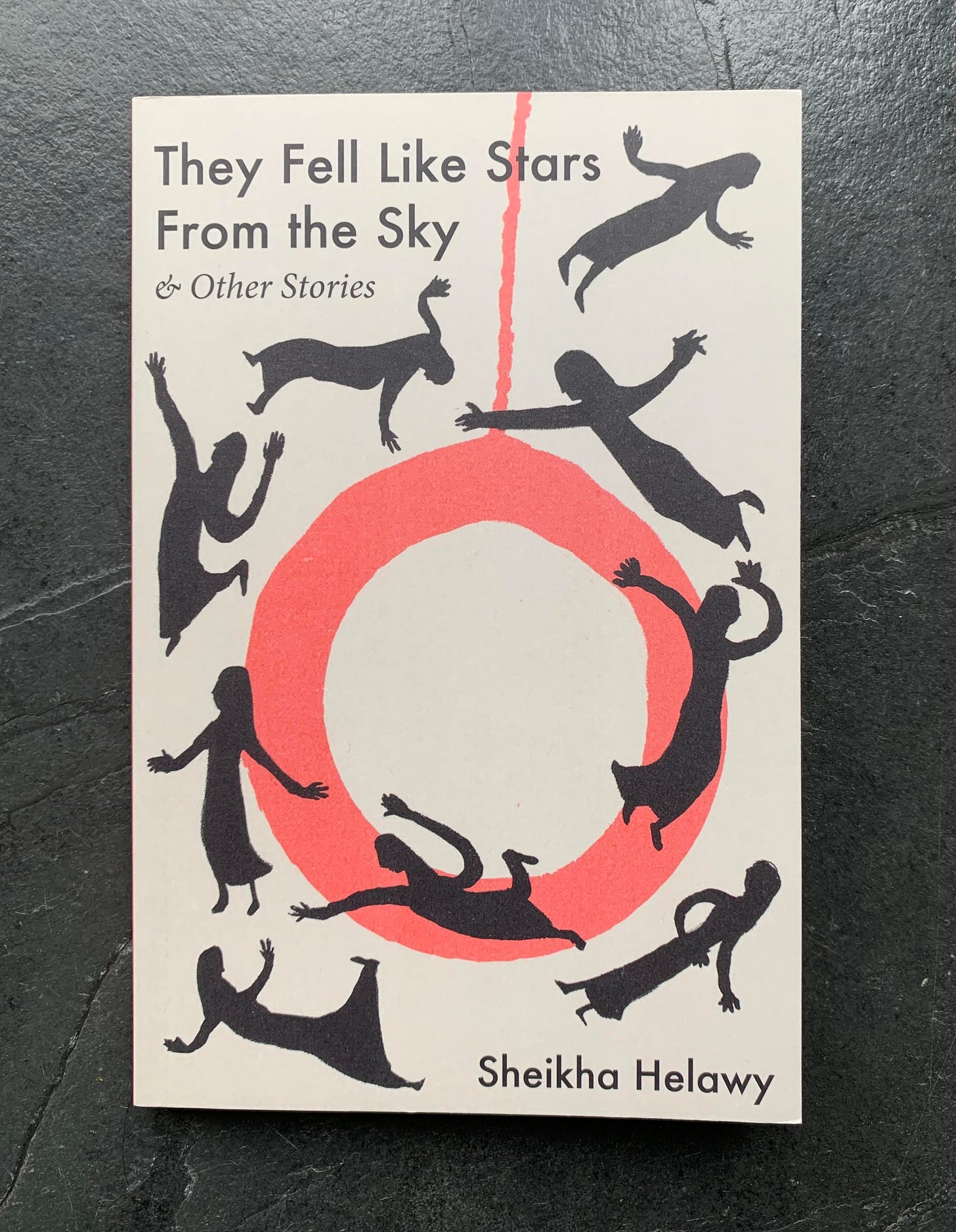

‘s comments on ‘Beloved’ and thought she captured the essence of the book so well. I will link here for those who want more ‘Beloved’ commentary.‘They Fell Like Stars From The Sky & Other Stories’ by Sheikha Helawy is a short story collection that celebrates the resilience and courage of Bedouin women and girls from Palestine. This collection of eighteen stories celebrate the courage, tragedies and triumphs of these women from their marginalised communities. The stories are reflective and emotional, challenging societal norms, gender roles and womanhood. From a woman whose tattoo arouses the alarm of sexual taboos, to girls whose curiosities of womanhood spark endearment and the tragic outcome of a husband consumed by jealousy; these stories offer portraits of life on the margins.

The ‘Bedouin’ are an indigenous people of the Negev desert in southern Israel. They are a semi nomadic community that engaged in animal herding, grazing and agriculture. They are historically a deeply conservative community. After the Nakba7 many of the most significant tasks of the Bedouin women were taken away from them.8 The Bedouin village that Helawy was brought up in has since been demolished for an Israeli railway. The confiscation of their lands and forced relocation has enormously impacted the community and strongly altered their lifestyle. I therefore had the assumption that this short story collection would be political and sharp, and it is, but in a much gentler way.

The stories explore so many aspects which are inherent and universal to femininity. They discuss relationships with body, hair, puberty, love, and maternity. As well as the experience of being sexualised at a young age and what it means to be a woman in a male dominated community. The stories are tender and notable as they detail the spirit of these women. My favourite stories were; ‘Haifa Assassinated My Braid’, a girl's experience with wanting to cut her long hair to break from her Bedouin tradition and become a ‘city’ girl. This desire to be modern and reject her tradition is initially irresistible to her. ‘Pink Dress’ is the story of a girl going against her mothers wishes to not touch her body hair and deciding to shave her legs for an event where the pink dress she is wearing shows them. I smirked at the disdain of her mother and felt the elation of the girl in using a razor for the first time and achieving perfectly smooth legs.

‘Umm Kulthum’s Intercessor’ is the story of Habiba’s grandmother who loves the singer Umm Kulthum. For her birthday, Habiba photoshops an image of Umm Kulthum (who is dead) and her grandmother together so she can hang it on her wall. She is beyond ecstatic and is the envy of the village. Her grandmother's adoration for Umm Kulthum is the foundation of their relationship, growing stronger with every song. Until one day Habiba decides to tell her grandmother about the allegations that Umm Kulthum is a lesbian. ‘The Door to the Body’ is the story of Selma’s parents trying to send her off to boarding school because she is at risk of attracting male attention. Her parents are obsessed with her body and how others might view it.

I thought this collection of short stories were good. I enjoyed that they were all authored by Helawy so there was a continuity within her voice and tone throughout all eighteen stories. I thought the focus on female experience and friendship within the Bedouin culture was well done. They gave insight into their traditions and is not at all a story of weak women suppressed by a restrictive culture but of resilient women who indulge in rebellions where they can. The protagonists range from young girls to old women with a wonderfully varied perspective and all with a tenacity of spirit. As with all short story collections some were much better than others. A few for me lacked structure and conclusive endpoints of the tales.

I would call ‘They Fell Like Stars From the Sky’ a borrow. I would recommend it less so as a must read anthology, and more so as a book about a culture that you rarely (if ever) get to experience in fiction. I thought the anthology gave a much needed reminder of the universal experience of girlhood, and how across the globe we are much more alike than we are led to believe. We are not as different as we think we are, we are all human. My heart goes out to the women of this story right now.

And that concludes my February Reads! My favourite reads of this month were ‘Close To Home’ and ‘Will and Testament’ - I loved them both so much.

My first read of March is ‘Suncatcher’ by Romesh Gunesekera. It is a novel about two boys friendship set among the tumult of 1960s Sri Lanka. It was shortlisted for The Jhalak Prize in 2020, a prize all about celebrating books written by British BAME writers.

My Classic Novel Goal for 2024

My classic novel goal will follow no title order, just one classic a month. I am undecided on which title to choose next from my shelf.

Which should I read next?

East of Eden by John Steinbeck

Jazz by Toni Morrison

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

If Beale Street Could Talk by James Baldwin

The Woman in the Dunes by Kobo Abe

The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov.

However, these titles won’t take me to the end of the year! Therefore, I am turning to you, to ask what are your favourite classics and why? I read ‘The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter’ by Carson McCullers last year and am interested in more of her work. I also read ‘Vile Bodies’ by Evelyn Waugh and enjoyed his sharp wit.

My friends

, and have all posted great reviews recently for Middlemarch by George Eliot, The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton and And An Apprenticeship or The Book of Pleasures by Clarice Lispector which I am all considering. Especially Clarice Lispector who I have had my eye on for a while.☞ In other book news, the Women’s Prize for Non Fiction Longlist has been announced! This is the first year the Non-Fiction prize is running and I would encourage you to check out this list. I am so pleased to see that ‘How To Say Babylon’ by Safiya Sinclair has been longlisted.

From the list I have ordered; ‘Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in the Philippines’ by Patricia Evangelista and ‘Intervals’ by Marianne Brooker. I will also be patiently waiting for ‘Shadows At Noon’ by Joya Chatterji to come out in paperback this summer - right now it's only out in hardback and I absolutely do not have £30 to spare for that. The patient game of waiting for paperbacks is one I know well as a partial hardback hater.

Let me know your thoughts:

What’s your favourite classic novel and why?

What have you read and enjoyed in February?

Have you read any of these books? What did you think?

Thank you, as always, for reading and enjoying (I hope) this newsletter. I love writing them so much. I know they end up being very long and I appreciate anyone who takes the time to read and engage with all I have to say. ♥︎

See you next month! March is a big month for fiction prizes; the Women’s Prize for Fiction and The International Booker Prize longlists will both be announced - rest assured we will discuss once they arrive.

Happy Reading! Love Martha

Thank you for reading Martha’s Monthly!

If you know someone who is always reading, forward them this newsletter!

Hit the little heart at the top or bottom of this email to let me know you enjoyed it <3

Catch up on what you might have missed:

Did you enjoy this post and the types of books I discuss? Subscribe! and never miss an opportunity to discover new and interesting books to read.

It is scientifically proven that reading makes you cooler.

Subscribing to Martha’s Monthly makes you even cooler.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/11/the-cultural-revolution-50-years-on-all-you-need-to-know-about-chinas-political-convulsion

https://www.irishtimes.com/news/health/mental-health-problems-the-hidden-legacy-of-the-troubles-1.4005470

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/books/story/2023-05-19/the-working-class-belfast-born-author-trying-to-reinvent-the-post-troubles-novel#:~:text=%E2%80%9CClose%20to%20Home%E2%80%9D%20heralds%20a,over%20Belfast%20noir%20any%20day

‘ You must believe the illustrations but ignore the evidence. You can eat the pictures, but no one actually cooks from it’ is a quote from p58 in ‘Things I Didn’t Throw Out’

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polish_People%27s_Republic#Demographics

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/dec/22/boohoo-selling-clothes-made-by-pakistani-workers-who-earned-29p-an-hour AND https://cleanclothes.org/issues/migrants-in-depth/stories/slave-like-conditions-at-zara-supplier

‘Nakba’ means catastrophic in arabic referring to the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, were Palestinian’s were forcibly relocated

https://thisweekinpalestine.com/bedouin-women/ or The Guardian released this picture piece on the Bedouin the other day https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2024/feb/27/petra-basnakova-photos-desert-bedouin-people

In Cold Blood was one of the best books I have ever read. I watched both movies, as well.

your wrap up is SLAYING my TBR - so many good finds in here I haven't heard of and now need to read :)