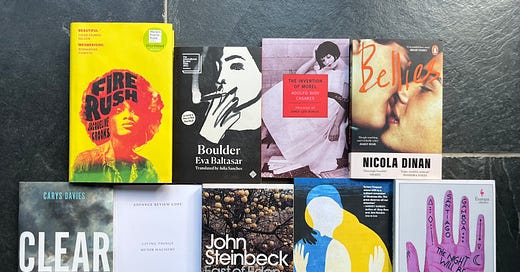

Welcome to Martha’s Monthly, June Reads edition! I really struggled to find a theme for this month. While some of the books this month explored human connection and relationships, which is in a sense a theme, it felt too broad and unspecific. I didn’t want to force it, so we are theme-less for June! However, with the overriding success of the books this month, I think the theme is just great books.

To see the translated reads from June on Martha’s Map, including authors from Spain, Argentina, Ukraine and Colombia, click here.

For those who are new, buy, borrow, bust is my recommendation key. Buy = I immensely enjoyed and heavily recommend this book. Borrow = I think this book is still well worth a read and I’m glad I read it. Bust = I wouldn’t recommend this book from my own reading experience.

Let the book fun begin!

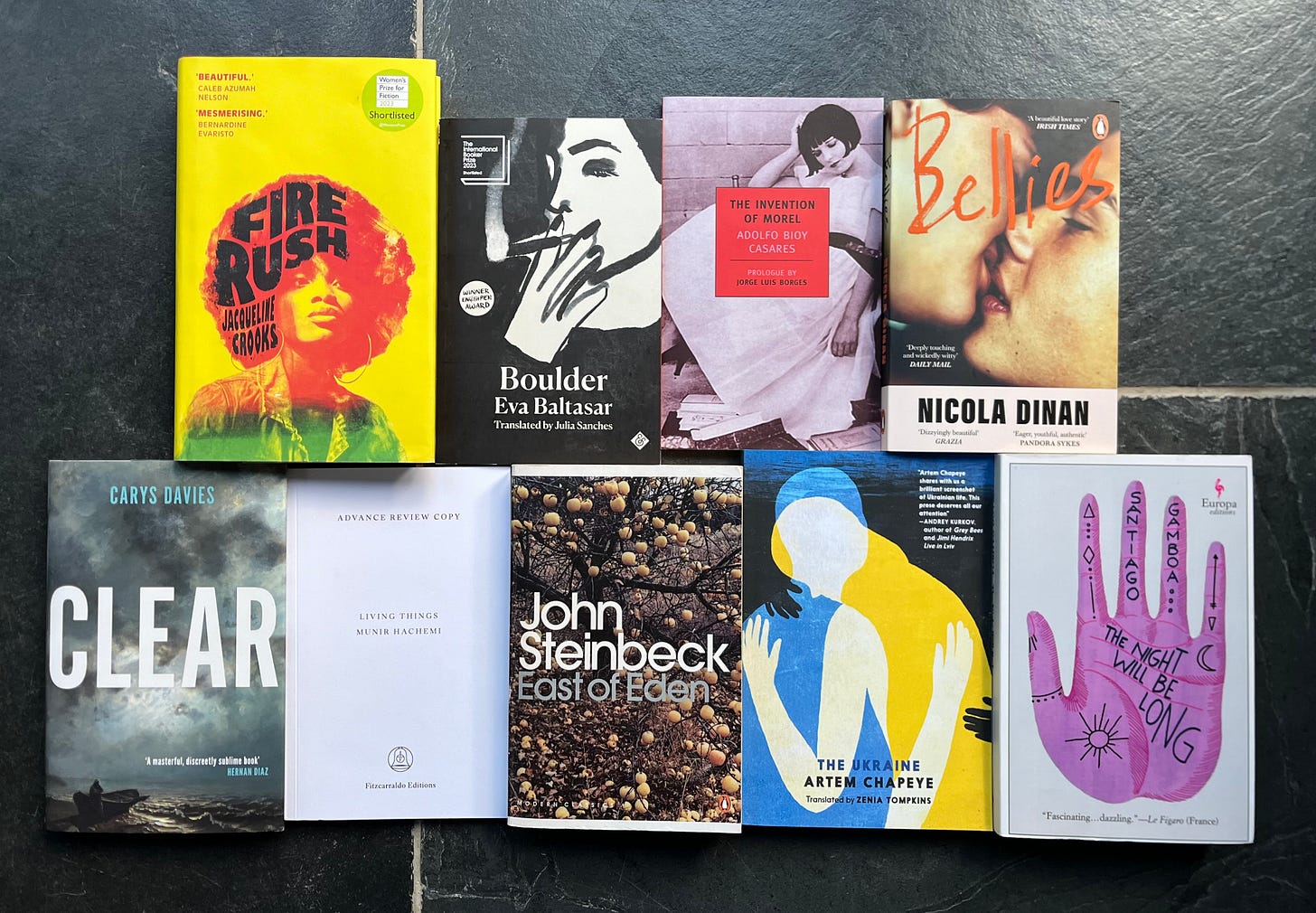

‘East of Eden’ by John Steinbeck is set in the rich farmland of Salinas Valley, California. It is home to two families whose destinies are fruitfully, and fatally, intertwined. Over several generations, between the beginning of the twentieth century and the end of the First World War, the Trasks and the Hamiltons helplessly replay the fall of Adam and Eve and the murderous rivalry of Cain and Abel. ‘East of Eden’ is a complex character-driven story that explores what it means to be human. Through the timeless and universal themes of love, identity and the struggle between good and evil, ‘East of Eden’ immerses us into a rich atmospheric tale of family and humanity.

‘East of Eden’ is often considered Steinbeck’s magnum opus. This book was a fundamental motivation for my classic novel reading goal for this year, because I knew I had to stop overlooking it on my shelf. While the merit of ‘East of Eden’ has never been understated, I am now here to join the throngs of Steinbeck fans that have praised his work for decades.

Despite being written in 1952, I was struck by how readable ‘East of Eden’ was. Accessible and full of scandal, the story has a real nature of fun and timelessness to it. I was in awe of the way Steinbeck constructed such a captivating narrative that spanned sixty years. The richness of this generational story feels challenging to articulate in a review, because the world Steinbeck creates is layered, complicated and absorbing. One of the most predominant themes in ‘East of Eden’ is an exploration of free will, fate and your relationship with destiny; do you think you can control your future? This theme lies within all the characters, but most interestingly Cathy and Lee. (Because ‘East of Eden’ is so widely read and known, I am going to indulge in a brief analysis of a character that may be a slight spoiler for those who haven’t read it, so proceed with caution)

Cathy was, without a doubt, my favourite character. Written to represent Satan, she is everything a woman in the twentieth century would have been condemned for. From her selfish nature and sexual conquests, she is presented to be this morally corrupt, abhorrent character. Written in the early twentieth century, it is unsurprising Steinbeck has associated true evil with female sexual agency and autonomy. This sentiment was definitely reflected in the initial reviews of ‘East of Eden’;

‘[Steinbeck’s] obsession with naked animality, brute violence, and the dark wickedness of the human mind remains so overriding that what there is of beauty and understanding is subordinated and almost extinguished’ - ‘The Christian Science Monitor’ reviewing ‘East of Eden’ in 1952 1

Cathy was clearly received as a wicked character that stripped all beauty about humanity from the book. While I understand the sinister intention of Cathy’s character, and why in 1950 she was received this way, I deeply enjoyed Cathy's stoicism and aspiration. After all, she achieves what many women from that time only dreamt of; autonomy and control. Initially, I was convinced Steinbeck was writing from a place of misogyny, only writing a character like Cathy from a position of hating women - however, I think it's possible that Steinbeck is interrogating the patriarchy. Perhaps surprisingly, Steinbeck could be questioning the default position to not see women as beings with agency and power. Ultimately, Cathy is one of the only characters who does not succumb to a prescribed ‘fate’. Nothing happens to her without her decision, even in death. She has a starkly different relationship with free will and destiny, whereby she believes she can create and attain the future she wants, while some men in the story fail to enact, quite literally, anything (Adam and Aron, I’m looking at you).

I don’t think ‘East of Eden’ is a piece of feminist literature, and I do think the criticisms of misogyny within the novel are valid. It is evident ‘East of Eden’s’ ideal woman is a domesticated one, and this is unsurprising as it reflects the attitudes of the time. However, I do believe Steinbeck is attempting to explore that Cathy is not a monster for rejecting societal expectations. Instead, exploring that the devil is not within her, but within the gender roles and restraints society tethers to women. I did not anticipate this exploration about the position of women in society from ‘East of Eden’. I am also aware this is perhaps a modern reading of the text, and one that might not have been so considered many years ago. The overall sentiment that Steinbeck is communicating throughout the text is the flawed nature of humanity; which is a timeless perspective that holds court.

I was also deeply interested in Lee’s character; how he is initially introduced to us contrasting to the man he ends up becoming. I could write an entire newsletter piece just analysing ‘East of Eden’ and everything this tome explores, but I will stop here. It goes without saying, but I really would recommend this book if you haven’t already read it. The generational story is incredibly absorbing and following the families for six-hundred-pages is as fun as it is thought provoking. ‘East of Eden’ is a buy and I think it might be my favourite classic so far! It has given me much more confidence for when I tackle ‘Crime and Punishment’ by Fyodor Dostoevsky later this year! Thank you for reading this with me

, it was a lot of fun.Anyone who has read ‘East of Eden’ - please meet me in the comments, I have so much to say! What Steinbeck should I read next?

‘Living Things’ by Munir Hachemi follows four recent graduates who travel from Madrid to the south of France to work the grape harvest. They set out in search of adventure, but things don’t go as planned and they end up working on an industrial chicken farm and living on a campsite. After a period of youthful hilarity, an atmosphere of menace takes hold. What follows is a compelling and incisive examination of precarious employment, capitalism, immigration and the mass production of living things.

A fast paced philosophical novel, ‘Living Things’ explores aspects of the modern world; class, animal cruelty, the food industry and precarious employment. Hachemi explores capitalism in an experimental way. It reminded me deeply of ‘On The Line’ and while that had a poetic exploitation of labour, ‘Living Things’ is much more horrifying. Both explore the inhumane relationship we have with food production and the dehumanising position those who work in these environments are put in. However, where they differ is this sense of impending dread that ‘Living Things’ creates on the page. Hachemi’s prose creates a deeply weird and horrifying tale where you are led to believe that something otherworldly is at play. But instead, the horror at play is just the world we live in.

‘It suddenly dawned on me that some are cut out for this work and some aren’t. Then I realised that that wasn’t a factual statement but a kind of classism that justified my sense of superiority. I have a degree, and will eventually find a job - a precarious one for sure, but definitely better than this one - where I won’t have to torture living beings or be tortured for money’ - p.60 in ‘Living Things’

‘Living Things’ explores the relationship between immigrant labour and food production, something which is often concealed. Hachemi endeavours to examine how a job about the mass production of animals and food under capitalism thrives off the exploitation of immigrant labour. 2 ‘Living Things’ addresses how foreign labourers are often invisible and barbarically exploited. While it is hard to explore some of the facets of this story without spoiling the plot, just know that this thriller is multilayered and surprising.

Hachemi seamlessly constructs a very atmospheric and clever story. ‘Living Things’ is layered; on the surface we have the boys seemingly on an adventure, but underneath something horrifying is taking place. ‘Living Things’ is metafictional, commenting on the power of memory and the art of writing. How do we connect the experience of reality and choose to tell those realities as a story? Our protagonist, Munir, consistently reminds us that he is writing everything from memory, creating this distance from the events, the author and us as the reader. It suggests that there are perhaps elements of the story he cannot share, for they are too horrific to remember. Hachemi plays with the written word, memory and reality to create an incredibly impressive, and disturbing, tale.

I really enjoyed reading this and would really recommend it, especially to readers who enjoy critiquing capitalism, the mass production of animals for food and writers' relationships to writing and the power of memory. I would call ‘Living Things’ a buy, it was light hearted and intense in equal measure, which is an impressive dynamic to create. I am really intrigued to read more of Hachemi’s work.

Thank you Fitzcarraldo Editions for this ARC. ‘Living Things’ is out now.

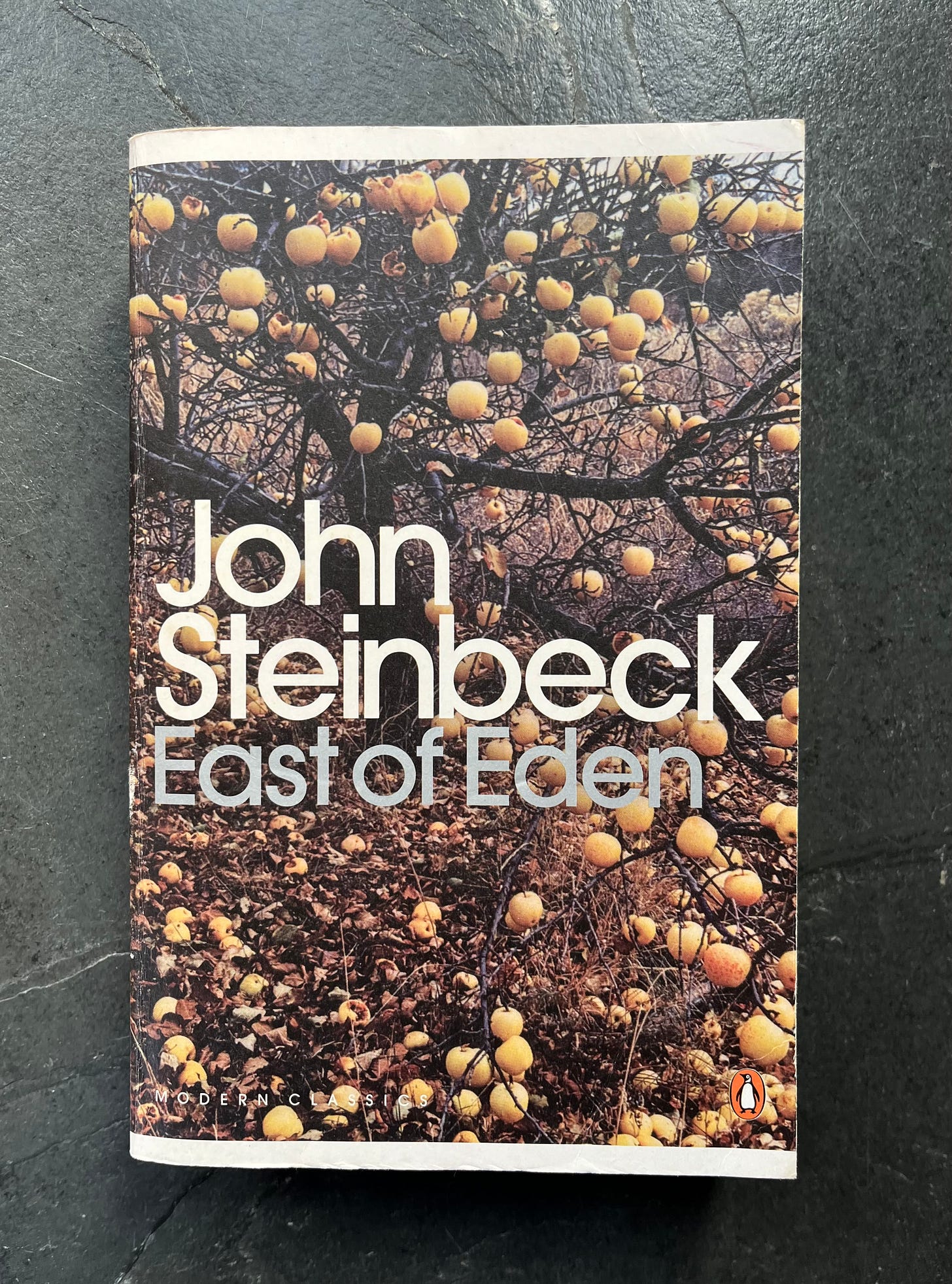

‘The Invention of Morel’ by Adolfo Bioy Casares. A fugitive man arrives on a mysterious island around Polynesia, where he finds some deserted buildings. Tortured by solitude, he is in despair. Suddenly everything changes as he falls in love at first sight with a beautiful lady. But there is something wrong, as she doesn’t seem to notice or care about anything he does or says. A story of suspense and exploration, ‘The Invention of Morel’ is a tale of isolation, love and the blurry lines of reality.

‘The Invention of Morel’ was a deceptive read. Immersing the reader into the abyss, the initial experience of reading this novel is confusion. It reminded me of ‘Piransei’ by Susanna Clarke, where you are launched into the unknown by the author. I think this style of narration always pays off, despite being plunged into a world blind. In the prologue, Jorge Luis Borges describes it as ‘perfectly plotted’ and while I am not sure I completely agree, the pacing does align with a building sense of adventure and suspense as we try to understand life on this mysterious island.

Hidden among the mystery, Bioy Casares explores ideas about morality, the pursuit of immortality and the enduring power of love. ‘The Invention of Morel’ delights in philosophical explorations, questioning the ethics of playing with immortality. To read this in 2024, where our relationship with time and technology is the most prominent it has ever been, was thought provoking. Bioy Casares also plays with the enduring power of love, questioning where love ends and obsession begins. The novella ponders on the philosophical; can you really love someone you don’t know? What is the relationship between the body and soul?

‘The Invention of Morel’ is a novella that is perhaps at its most enjoyable once you’ve finished it. While the mystery and suspense is not something to be overlooked, the richness of this story can only be understood at the end. When the mystery reveals itself, the reader is left with a plethora of questions about humanity, such as where our life ends and begins. I appreciated the way this novella made me think over the experience of reading it. In many ways it reminded me of ‘A Shining’ by Jon Fosse which also offered such richness in thought once the book has been put down.

I apologise for being so vague in attempting to review ‘The Invention of Morel’, but I hope you can understand this is a novella where the less you know, the better. 3 I would call this a borrow, and would recommend it to anyone who enjoys reading books with a deep sense of mystery and the unknown. While it is dense at times, it is a fun foray into the metaphysical.

‘Bellies’ by Nicola Dinan begins as your typical boy meets boy love story. Tom and Ming meet on a night out at university and fall hard for each other. Their connection is instant and Tom finds himself deeply drawn into Ming’s orbit. On the cusp of graduation, Tom’s already mapped out their future together. Then, Ming reveals her intention to transition. We follow Tom and Ming as they face shifts in their relationship, and confront the vastly different shapes their lives have taken, in the wake of Ming’s transition. They both have to grapple with whether they have to lose each other in order to become the people they want to be.

‘Bellies’ is an utterly absorbing and nuanced coming-of-age story about queer identity and self discovery. It’s a really tender story about love and all that it can encompass; as well as what it can and can’t withstand. Dinan’s writing was exceptional as she takes us on a deeply emotional journey through the landscape of queer identity. Through Tom and Ming, ‘Bellies’ explores an honest look at gender, sexuality and identity and how they can be so tightly wound in love, and loving someone. All the relationships between the characters within the story were brilliantly constructed and full of warmth. It felt like we were witnessing a genuine collection of friends and lovers; people looking to be loved and understood for who they are. ‘Bellies’ explores not just love within romantic relationships, but love within platonic relationships as well. I thought the portrayal of friendship within this novel was exceptional.

Along with the rich atmosphere of love and kindness on the page, Dinan flawlessly communicates the exceptionally confronting and challenging aspects of transitioning. I thought Dinan’s exploration of gender dysphoria through Ming’s character was extraordinary, emphasising the terror and freedom that come with transitioning. Ming’s story is intimate, tender and beautiful as she courageously embarks on transitioning into who she is meant to be. Equally, the exploration of identity with Tom was very moving, as he struggles with understanding what he truly wants, romantically and within his career. ‘Bellies’ reads as a deeply honest and real exploration of growing up and trying to understand who you are.

I really really loved this. ‘Bellies’ was so readable, and reminded me of Sally Rooney’s writing that similarly explores authentic and youthful love. Dinan’s humour about recently graduated professionals in London was fantastic. I saw a lot of my peers in this book who are deeply unsure about whether the decisions they are making are the right ones. I am so excited to see what Dinan writes next. I felt so much love and emotion towards Tom and Ming, it was such a pleasure to read their stories.

I would, without a doubt, recommend ‘Bellies’ and call it a buy. There is a TV adaptation happening for Bellies from the same production company as Normal People, so I look forward to being absolutely devastated by this beautiful love story all over again. I hope they do it justice.

‘Clear’ by Carys Davies. In 1843, on a small island off the north coast of Scotland, lives Ivar. He is the sole occupant and leads a quiet life of isolation, with only the animals and sea for company, until he finds a man unconscious and badly injured on the beach below the cliffs. The man is John Ferguson, an impoverished church minister sent to evict Ivar and turn the island into grazing land for sheep. Unaware of the stranger's intentions, Ivar takes John into his home to help him and tend to his wounds. In spite of the two men having no common language, they begin to form a bond.

‘Clear’ is an incredibly poignant novel that explores the value of human connections and the power of friendship. Davies explores the significance of connection between people, and how important it is for us. The relationship between John and Ivar is touching, and beautiful, to witness. Davies creates a profound portrayal of both solitude and connection. ‘Clear’ also questions the structures of society, like religion, and the questionable rules religion can bring. The prose was beautiful and simple as Davies explores the value and role of language in forming intimate connections.

‘Clear’ is also a reflective story about the strong relationship between land and those who tend to it. By forcibly removing Ivar, ‘Clear’ communicates the lengths that were taken in order to make room for profit. It emphasises how no settlement is too small, or too isolated, to destroy and profit off. Ivar’s character explores a lost way of life, demonstrating the value he has because of his intimate relationship with the land. Ivar possesses knowledge and skill that allow him to survive alone on the island, as well as tend to John. There is a stark difference created between John and Ivar and their relationship to modernity. ‘Clear’ reflects on this dying way of life and how it is just as important, but because it can’t be exploited for profit, it has been eradicated.

While the story of ‘Clear’ is imagined, it takes place within a turbulent period of history. The period of 1750 to 1860 saw the ‘Great Disruption of the Scottish Church’, whereby whole communities of the rural poor were forcibly removed from their homes by landowners to make way for crops, cattle and sheep.4 The consequences of the clearances were catastrophic for an entire section of Scottish society that was no longer wanted.5 Thousands were evicted and driven by famine to leave their home, and with this, their native languages also evaporated. 6 The exploration of isolation and language in ‘Clear’ reminded me strongly of the themes in ‘The Colony’ by Audrey Magee. Ivar’s disposition reminded me of the islanders, who were also being forcibly removed, in ‘This Other Eden’ by Paul Harding.

This book was concise, impressive and I really enjoyed reading it. ‘Clear’ was an intriguing and emotional novella that beautifully explores loneliness, and connection. It was a fun and thrilling read in equal measure, an easy and immediately engaging book. I would definitely recommend ‘Clear’ and call it a buy!

‘The Ukraine’ by Artem Chapeye is a collection of twenty six pieces that intentionally blur the lines between fiction and nonfiction to create a masterful portrayal of a country. ‘The Ukraine’ tells the stories of a country through the people the narrator encounters in the towns, villages and desolate stretches of land. Chapeye moves through the landscapes of Ukraine to help tell the stories of those who live within them. From the Chernobyl irradiated zone, to the mountainsides where bears awaken in midwinter thaws and neglected towns, Chapeye creates a compassionate and contemporary picture of life amid an unending war; a perspective of life in a country which is often overlooked.

Since the invasion in February 2022 I have been meaning to read more Ukrainian literature. This collection of short stories was magnificent as they share so much about Ukraine in such a subtle and familiar style. Chapeye weaves information about the economy, the political landscape and society in a profoundly effortless way. I was in awe at how much I was learning and understanding about Ukraine through these enjoyable fictional snapshots. The stories explore what life is like in some areas of Ukraine, where traditions and modernity are at conflict, where generational differences are more contrasting than ever.

‘The Ukraine’ touches on the relationship the country has to gender, race, violence and wealth. Chapeye offers highly nuanced explorations of the workforce and the relationship to labour, and how little wealth there is in some areas. Beautifully and captivatingly written, ‘The Ukraine’ manages to present the intricacy of life which is tender and urgent. My favourite aspect was the emotion Chapeye emits within his writing about the people of Ukraine. He writes from a position of love towards the country and those within it, expressing they are deeply kind, hospitable and helpful people. Chapeye suggests Ukraine and the people, are often overlooked;

‘Inside everyone there’s a universe, a gigantic cosmos brimming with stars. And so be it that an uninviting exterior, humdrum labour, thoughtless amusements, and squabbles over money often keep it from being seen. Sometimes people forget that exists inside them. Sometimes we do too. [...] People are beautiful, even if they don’t realise it’ - p.265 in ‘The Ukraine’

It is rare to come across a short story collection as strong as this. I really, really enjoyed the diverse variety of stories and anecdotes throughout ‘The Ukraine’. The prose is beautiful and I was very impressed with Chapeye’s ability to capture the country within this collection. I would recommend ‘The Ukraine’ and call it a buy.

‘The Night Will Be Long’ by Santiago Gamboa is a thriller about corruption within the foundations of the Churches in Latin America. When a horribly violent confrontation occurs outside of Cauca, Colombia, only a young boy is around to witness it. But no sooner does the violence happen than it disappears, vanishing without a trace. Nobody claims to have heard anything, until an anonymous accusation catalyses a dangerous investigation into the deep underbelly of the Christian churches present today in Latin America. Bogotá prosecutor Edilson Jutsiñamuy, journalist Julieta Lezama, and her assistant, a former FARC guerrilla named Johanna, form a trio of flawed heroes to try and solve the case. A dark and twisty thriller, ‘The Night Will Be Long’ weaves together themes of corruption, crime and suspense to create a story that grips you until the end.

This book was so much fun to read. While ‘The Night Will Be Long’ is a heavily plot driven story, the protagonists are deeply likeable and Gamboa fosters rich context surrounding their hopes and fears that create an enthralling read. The action is expertly described, and the incident so dramatic, that I was picking up the book to read at every chance I could get; it was an intoxicating read. Though at its heart, the story is about finding out who was involved in the violent confrontation, Gamboa also threads aspects of Colombia culture throughout. Touching on the history of guerrillas in the country, to mining and cultural conflicts, ‘The Night Will Be Long’ offers up a rich tapestry of the landscape of Colombia. I especially valued the, albeit slight, insight into some of the Indigenous population in Colombia, known as the Nasa.

Primarily, the aspect of Colombian culture that is explored the most within the novel is corruption. Exploring police and journalistic practices and the violence that dominates the landscape, Gamboa is blurring the lines between reality and fiction to communicate the state of the nation. Gamboa is a journalist and you can sense that while reading. The prose is packed with observation and insight about the socioeconomic state of Colombia, positioning the fictional story within an incredibly rich, and real, picture of Cauca.

‘The Night Will Be Long’ is awash with deep character assessments and incredibly dialogue heavy writing. While this could be too much for some, that is a style of writing I deeply enjoy reading because it only adds to the absorbing nature of the plot. So here is my caution that while I do heavily recommend this, it is wordy as hell.

‘The Night Will Be Long’ is an absolute buy for me. I would recommend it if you are looking for a rich, detailed page turner. I really want to read more from this author, I am seriously impressed by his writing. He published ‘Colombian Psycho’ in 2021, so I will be keeping my eyes peeled for when the translation of that gets picked up! Other works of his that are available in English include; ‘Necropolis’, ‘Night Prayers’ and ‘Return to the Dark Valley’ - all of which I will endeavour to read.

‘Boulder’ by Eva Baltasar is the tale of a cook on a merchant ship who comes to know, and love, a woman named Samsa. Samsa gives her the nickname ‘Boulder’. When Samsa gets a job in Reykjavik, the couple decide it is only natural to move in together. Then, Samsa declares she wants to have a child. She is already forty and she can’t let the opportunity pass her by. Boulder is not interested in having a child, but has no idea how to say no. Her lack of communication skills lead her to getting dragged into a life she does not want. When motherhood changes Samsa into a stranger, Boulder struggles to cope and must decide where her priorities lie, and whether she can communicate her true feelings.

‘Boulder’ has been on my to-read list for a while, endorsed heavily by my friend

for its chilling plot and fascinating exploration of power dynamics within a relationship (you can find Mike’s review of ‘Boulder’ here).Boulder is, perhaps, the least maternal fictional character I may have ever read. A cook on a ship, who loves drinking and smoking, Boulder’s life is about freedom and movement. While the enjoyment of reading this novella relies on the unknown, I think it is safe for me to say that ‘Boulder’ is dripping in atmosphere and tension. There is this immediate unease as we witness Boulder being suffocated by Samsa. Samsa is doing everything to change her; from her name to her environment by making her move. Boulder, this deeply solitary and queer individual, gets anchored into this cosplaying of heteronormativity to appease her partner.

‘Impossible routes only seem impossible because they’re dangerous. The solitary ones - those we pay for with our lives’ - p.49 in Boulder

Through Boulder's struggle to be heard, Baltasar creates a raw exploration of desire, and conflict, within relationships. The narrative explores intimacy, miscommunication and autonomy inside relationships. Baltasar examines the idea of being suffocated by the person you love, and the conflict that can arise by having two people fighting for their desires to be heard.

Crucially, ‘Boulder’ explores the complexities of queer relationships. ‘Boulder’ is a rumination on what it means to be a mother, exploring the perspective of the queer partner who has not given birth. Instead of discussing pregnancy with beauty and miracle, the prose approaches motherhood in such a sinister and repulsive way, it is truly remarkable. It is such an abrupt and stark departure from the romanticised narrative of motherhood we are normally shown. Baltasar said that she wrote ‘Boulder’ because she wanted to get to know a woman who could embody a boulder;

‘A woman like that isolated, solitary rock; a living metaphor at the mercy of the elements and weather, with cracks that allowed me to dig into her and uncover the secret hardness inside’ 7

Deeply poetic in nature, the prose is impactful. There is not a single word wasted, each one holds weight. Dark and unconventional, ‘Boulder’ explores this inability we can have to express ourselves, to know our true desires. It sharply addresses societal expectations of women, as well as an unwillingness to be honest with ourselves.

I would absolutely recommend ‘Boulder’ and call it a buy! This weird, thought provoking book is one big incredible metaphor. Baltasar’s writing is beautiful and unconventional and I loved it. I have been lucky enough to receive the ARC of the next book in Baltasar’s trilogy; ‘Mammoth’ which comes out 6th August from the publisher. I will be reading it next month, and I am incredibly intrigued and excited to see how it compares, and contrasts, from ‘Boulder’. I read someone describe it as even more unhinged than Boulder, so I am braced for some disturbing prose. I am fascinated to see how Baltsar can take the disturbing one step further.

‘Fire Rush’ by Jacqueline Crooks is a moving and mesmerising tale of love, loss and freedom. Set amid the Jamaican diaspora in London in the 1980s, Yamaye lives for the weekend. She goes raving with her friends at The Crypt, an underground dub reggae club on the outskirts of London. Raised by her distant father after her mother’s disappearance when she was a girl, Yamaye finds an escapism within music. Everything changes when she meets Moose, who she falls deeply in love with, and who offers her the possibility of freedom and escape. But when their relationship is brutally cut short, Yamaye goes on a journey of transformation that takes her to Bristol, and then Jamaica. ‘Fire Rush’ is a novel that takes you on an emotional journey that explores the complexities of Black womanhood, culture and identity.

The plot for ‘Fire Rush’ was so rich and not what I expected going into this. Crooks tells a brutal story about Black lineage, the concept of home and maintaining relationships with your ancestors. What begins as a story about people and their love for music transforms into a tale of injustice. ‘Fire Rush’ at its core is about the Black community's relationship with Babylon. While reading I felt deeply grateful to have read ‘How To Say Babylon’ by Sinclair earlier this year, as that memoir gave me so much more understanding about the term Babylon and what it means, and represents, to the Black community. ‘Fire Rush’ is a fictional story positioned within so much historic political turmoil. Yamaye is living during an era of protests and uprisings against racism and police brutality across the UK in the 1980s.8

Dance and music play a huge role in this book, specifically dub reggae. In an interview with Crook she discussed what music represents in ‘Fire Rush’:

‘It was like our temple to commune together. Because the Black community, much like the Asian community, wasn’t welcomed into mainstream spaces, so we had to create our own. It was the politics of invisibility, migrants weren’t seen or welcomed. We went underground so as not to be seen or heard, otherwise the police knew where we were dancing and would raid it. [...] Dub reggae was the sound of revolution, it was a way of weaponising music to fight against racism and oppression that migrant communities were facing. It was a way of communicating and sounding out how we were feeling, a call to fight back. It was important for that reason. But also it was just pure joy, letting go at the end of the day, to dance and have freedom of movement.’ 9

The relationship between music, identity and justice within this story is powerful. Crooks writes an atmospheric story that is rich in rhythm. She also created a playlist for ‘Fire Rush’ which I deeply appreciated. It helps contextualise the tone of the lyrics found on the page.

Black history is everywhere in this book. Yamaye’s character, and those that surround her, communicate the generational trauma that lives within the Black community. ‘Fire Rush’ powerfully articulates that absence of lineage and understanding about your ancestors from the transatlantic slave trade. This ancestral absence is characterised with the loss of Yamaye’s mother, as she struggles to understand who she is and where she came from. This lack of knowledge is disorientating and suffocating for Yamaye, who feels adrift in not knowing who came before her. ‘Fire Rush’ stresses the necessary and important journey for the Black community in connecting to their ancestral roots.

While the book could have done with a tighter edit, as the beginning was significantly stronger than the end, I really appreciated what Crooks was trying to do with this novel. The narrative is sprawling, but it stays rooted in its charge with anger and passion. ‘Fire Rush’ was such a rich story that I would recommend and call a borrow. It is a haunting novel that is influenced by Crooks own life. I read in an interview that Crooks was tired of only reading dub reggae books about men, and wanted to write about women’s experience in the Black sound revolution and the different ways women rebel. I’m pleased Crooks was able to write the book she wanted to exist.10

And that concludes my June Reads! I enjoyed so many books from this month that picking a favourite feels very hard! I loved Bellies for the way it made me feel (cry), Boulder for the absurdity, The Night Will Be Long for being so much fun and East of Eden for being an absorbing family saga.

My first read for July is ‘All Our Yesterdays’ by Natalia Ginzburg which is translated from Italian. Sally Rooney describes ‘All Our Yesterdays’ as one of the great novels of its century and a book that transformed her life!! I am as nervous as I am excited to read an author who means so much to Rooney.

Today is special newsletter edition because it’s Martha’s Monthly’s first birthday! I started this newsletter because I was desperate for something to focus on. I spend a lot of time at home and by myself, not by choice, because I am in treatment for a health condition that has limited my life extensively. The experience of being in treatment is painful, exhausting and very boring. Reading became one of the only things I could do from the confinement of my bed. I cannot express how indispensable the ability to get lost in another world has been while my own has been in such turmoil. To be able to travel the world through literature, when I could not leave my bed.

This newsletter has brought me so much in the past year and I have met so many wonderful people. It brings me so much joy to talk about books with all of my lovely readers. Thank you to everyone who reads this newsletter, it means so much to me. I am unbelievably grateful for every single one of you. Writing Martha’s Monthly is my favourite thing in the world and my greatest pleasure. Thank you, whether you’ve been reading for a year or a day, for being interested in what I read and have to say.

Let me know your thoughts:

❀ What have you read and enjoyed in June?

❃ Have you read any of these books? What did you think?

❁ Do you have any recommendations for me based off the books from this month?

⚝ Is there a book you have read because this newsletter in the past year? If so, please share I’d really love to know!

Thank you, as always, for reading. Let me know if you found a book you’d like to read.

See you next month,

Happy Reading! Love Martha

If you know someone is always looking for interesting books to read, share this newsletter with them!

Catch up on what you might have missed:

And a moment to honour how far I have come in writing these, and to not fear being seen trying, I am going to share the first newsletter I ever posted this time last year. While the writing makes me slightly embarrassed, there are some really really great books are in here!

Before you go - if you enjoyed this, why not subscribe? <3

Quote found on p.viii in ‘Introduction’ written by David Wyatt in the 1992 Penguin Classics edition of ‘East of Eden’.

A few days after I finished reading ‘Living Things’, a story came out about immigrant labourers in Italy as one Indian farm worker was ‘left to die on the road, with a severed arm’. https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jun/20/indian-farm-worker-in-italy-left-to-die-on-road-with-severed-arm - this article eerily reflects the themes that ‘Living Things’ was exploring in relation to immigrant labour and food production - super interesting and depressing in equal measure.

Tame Impala pun intended x

The sentence about the history of the ‘Great Disruption’ lifted from the Authors note written by Carys Davies in ‘Clear’, p.148.

Ibid

Ibid, p.149

Quote from Baltasar lifted from this interview: https://thebookerprizes.com/the-booker-library/features/eva-baltasar-interview-i-wrote-three-versions-of-boulder-and-deleted

Info on the Southall protests in 1979 for all who are interested: https://lithub.com/on-deadly-policing-and-the-1979-southall-protests/

Quote lifted from this interview I found by

. If you are at all interested in reading ‘Fire Rush’ I’d really recommend this interview, it is informative and fascinating in regards to Crooks relationship with writing the novel, as well as the influences from her life that can be found in ‘Fire Rush’.Crooks expressing a desire for their to be dub reggae books written about women in this interview: https://www.womensprize.com/five-minutes-with-jacqueline-crooks/#:~:text=What%20inspired%20you%20to%20write,music%2C%20and%20language%20of%20today

East of Eden is one of my favourite books! Grapes of Wrath is next on my list by Steinbeck. I also surprisingly flew through Crime and Punishment, hope you enjoy it when you get to it! x

I read “East Of Eden” so long ago: as a teenager, I tried to read all of Steinbeck’s novels but didn’t really understand most of them. I am going to read it again.

I just finished “The Blue Sisters” by Coco Mellors. Wish it was longer: it was that good!

Now I’m almost halfway through enjoying book 1 of “On The Calculation of Volume” by Solvej Balle.

So many books, so little time!