May Reads

The cost of life under those who abuse their power + grief and the search for purpose

Welcome to Martha’s Monthly, May Reads edition! This month I gravitated to several political books exploring life under military dictatorships. May also included books which looked at labour and the workforce and the tendency of these notions being exploited by higher powers. Together these themes created a sentiment of the cost of life under those who abuse their power. There were also some more quietly reflective books about purpose and grief.

To see the translated reads from May on Martha’s Map, including authors from France, Czech Republic, Brazil, South Korea and Norway, click here.

For those who are new, buy, borrow, bust is my recommendation key. Buy = I immensely enjoyed and heavily recommend this book. Borrow = I think this book is still well worth a read and I’m glad I read it. Bust = I wouldn’t recommend this book from my own reading experience.

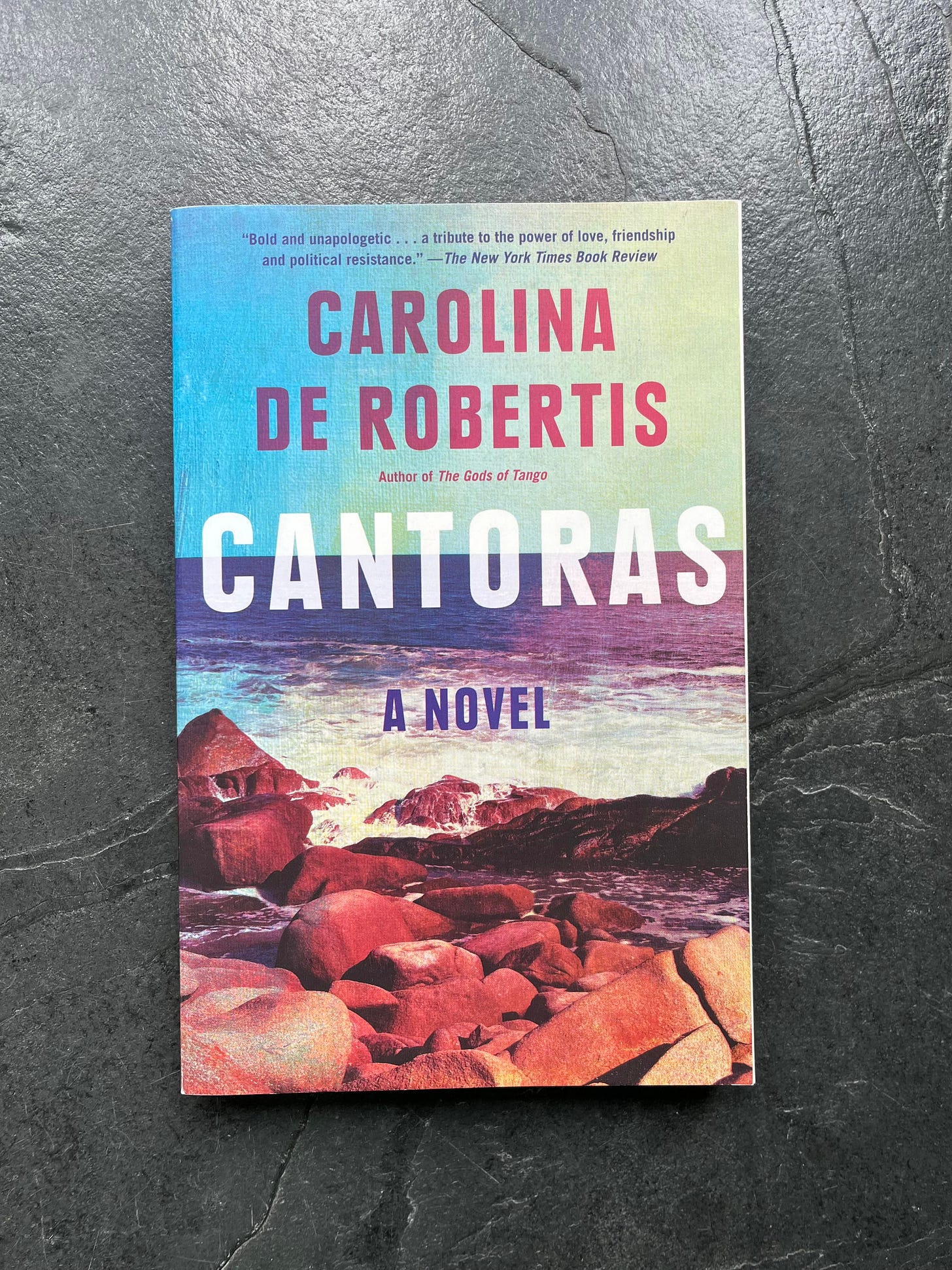

‘Cantoras’ by Carolina De Robertis is a beautiful portrait of queer love, community and forgotten history. In 1977 a brutal dictatorship took power in Uruguay. The everyday rights of people were under attack and homosexuality became a dangerous transgression. Five women miraculously find one another and together discover an isolated, almost uninhabited cape, which they claim as their secret sanctuary. Over the next thirty-five years their lives move back and forth from this secret sanctuary; sometimes together, sometimes in pairs, or sometimes alone. Throughout it all, the women are tested by their families, society and one another, as they fight to try and live authentic lives under the turbulent social and political landscape in Uruguay.

‘Cantoras’ is a poignant and powerful story set against the backdrop of a tumultuous historical period. It tells the story of complex and resilient women who defy societal norms. The story follows five queer women as they struggle with their identity and sexuality amid tyranny. ‘Cantoras’ is full of great depth and nuance, telling a beautiful story. It was the perfect historical fiction; not letting the history overpower the characterisation and storyline of the women. The political landscape is woven into their lives effortlessly and creates a comprehensive understanding of life under the dictatorship. Through this careful balance, De Robertis creates an incredibly enveloping story full of beautiful prose and characterisation. I have a real affinity with generational novels that explore how characters change overtime, and ‘Cantoras’ approached the ever changing story of five different women very well. With multiple protagonists there is always the fear that the prose could be too busy, but De Robertis balanced each of the women’s stories faultlessly.

While ‘Cantoras’ is a beautiful story, it is also harrowing. There is inevitable abuse that is expected to be explored when it comes to homosexuality under a dictatorship. ‘Cantroas’ approaches these topics tastefully. It would be a failure for De Robertis to write a book about queer people under a dictatorship without acknowledging and exploring the terror and abuse they would have experienced in that environment. De Robertis approaches it in a way that, as my friend

said, is not written for the edification of straight people. It truly honours those who did, and didn’t, survive. It speaks to the sentiment that a lot can be true, and exist, at the same time - a multifaceted look at oppression and resilience.It feels incomprehensible to think about life as a queer individual under a dictatorship. While that sentiment still stands, De Robertis brings to life what could have been, and it is bold and gripping. I would absolutely recommend ‘Cantoras’ and call it a buy. This is a really strong historical fiction and I would recommend it to anyone who enjoys the genre or perhaps is slightly intimidated by it - because this was incredibly accessible. I would also suggest it to lovers of ‘Homegoing’ by Yaa Gyasi because of the way the generational narrative is approached. For other books discussing dictatorships and queer people I would recommend ‘Call Me Cassandra’ by Marcial Gala.

Has anyone read De Robertis newest title ‘The President and the Frog’? Or any other of her work? I am eager to read more, so please let me know!

‘Some People Need Killing’ by Patricia Evangelista is an on-the-ground account of a nation careening into violent autocracy. Journalist Patricia Evangelista reports on the Philippines' drug war through harrowing accounts of state sanctioned killings. For six years Evangelista chronicled the killings carried out by police and vigilantes in the name of Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs, which led to the slaughter of thousands. By immersing herself in the world of killers and survivors, Evangelista captures the atmosphere of terror created when an elected president decides that some lives are worth less than others. Evangelista’s memoir is a feat of literary journalism, exploring the fragility of the Philippine’s democratic institutions under Duterte.

‘Some People Need Killing’ is a deeply fascinating political memoir that explores democracy, violence and the consequences of unchecked power. Evangelista starts off by exploring the history of the Philippines, from colonialism to the communist insurgency. This history is essential to understanding the political climate of the Philippines today, and it was fascinating to learn about a country's history that I have never encountered before. Evangelista positions her family, and herself, within the country’s history, helping us understand the dramatic socio-political changes that took place within a few generations of her family’s lifetime. Evangelista’s career within journalism develops alongside the rise of Rodrigo Duterte’s influence and role within the Philippines, giving her a front row seat to the violence.

Duterte started out as Mayor of the previously crime-ridden city of Davao. Davao saw the birth of Duterte’s intense anti-drug campaign and it is arguably what propelled him into being elected as president. He served in the presidential office for six years, from 2016 to 2022. It is impossible to report with any certainty the true death toll of Duterte’s war on drugs. Evangelista reports that even the highest estimate of over 30,000 dead is likely insufficient;

In the first six weeks of Duterte’s war, according to the police, 899 people were killed. [...] ‘the dead who were just floating along canals, the dead who were dumped along roads with their hands tied and their faces, eyes, and mouths taped, also those killed by riding-in-tandem, or those who were just shot’ - p.142 in ‘Some People Need Killing’

While Duterte’s election was democratic, Evangelista meticulously describes how his rise to power was deceitful and misleading. She lays out how he came to power; with the loopholes in the law and distortion of language that allowed him to define his actions as something other than state sanctioned murder. Evangelista goes into great detail to spell out for the reader how this came about, and is the product of the enormous spread of misinformation and fear mongering. She comments on the culture of misunderstanding about power, and the role of president, and how his hate directly incites violence. Evangelista details how these actions do not exist in a vacuum; from Duterte describing it as ‘Simple justice’ he said. ‘Not murder-murder’ to how the unlawful behaviour of the police has been building for years.1 They are being requested to turn a blind eye to vigilantes, to kill civilians, and suffer no consequences.

‘Some People Need Killing’ explores the cultural disconnect within understanding that Duterte, not suspected drug users, is responsible for the mass scale violence and murder across the nation. The violence that breaks out does not just appear due to criminals or drug users, but rather the result of direct orders from one individual only. Duterte directly creates financially incentivised killing, allowing ‘normal’ citizens the opportunity to help the ‘effort’ of the drug-war;

‘They were garbage truck operations, jeepney drivers, scavengers, security guards, construction workers - a small army of true believers who, at least at the beginning, considered themselves soldiers in Rodrigo Duterte’s war against drugs’ - p.236 in ‘Some People Need Killing’

Evangelista does an exceptional job of not criminalising anyone for their actions, and instead insightfully helps the reader understand the culture of violence that was endorsed, and encouraged, throughout the country;

‘I’m really not a bad guy. I’m not all bad. Some people need killing’ p.240 in ‘Some People Need Killing’

Under this gaze of moral performance, Evangelista appropriately comments on what happens when individual liberty gives way to encouraged state brutality. 2 As a reader there is a level of disconnect when reading an account such as this one. It is hard to understand how this could have happened; how Duterte was elected as president and carried out a brutal and terrifying rule. However this is because Evangelista does such an exceptional job as a journalist and writer, laying out a precise timeline of how this came to be. She witnessed it all as a trauma journalist and only after is able to create such a compelling and brave narrative about such a devastatingly violent chapter of Philippine history.

‘Some People Need Killing’ was a powerful, dense and intense memoir. But this is to be expected. While it was not a quick read, it was a deeply fascinating one. I learnt so much and felt disbelief that Duterte’s presidency has taken place so recently and I knew nothing about it. It is a gripping and captivating memoir which discusses the intersection between crime, politics and the abuse of power. I would recommend ‘Some People Need Killing’ for anyone who's interested, especially within the relationship between democracy and misinformation. I would call ‘Some People Need Killing’ a borrow. Evangelista, and those she interviewed, are so brave for writing this and I hope the book continues to make waves by bringing to life the names of those who were murdered. This memoir is not anti Duterte per say, it is about questioning and understanding why he is who he is, and understanding the story Duterte was intent on telling. If you are at all interested, I also enjoyed this interview of Evangelista talking about the process of writing and creating the book.

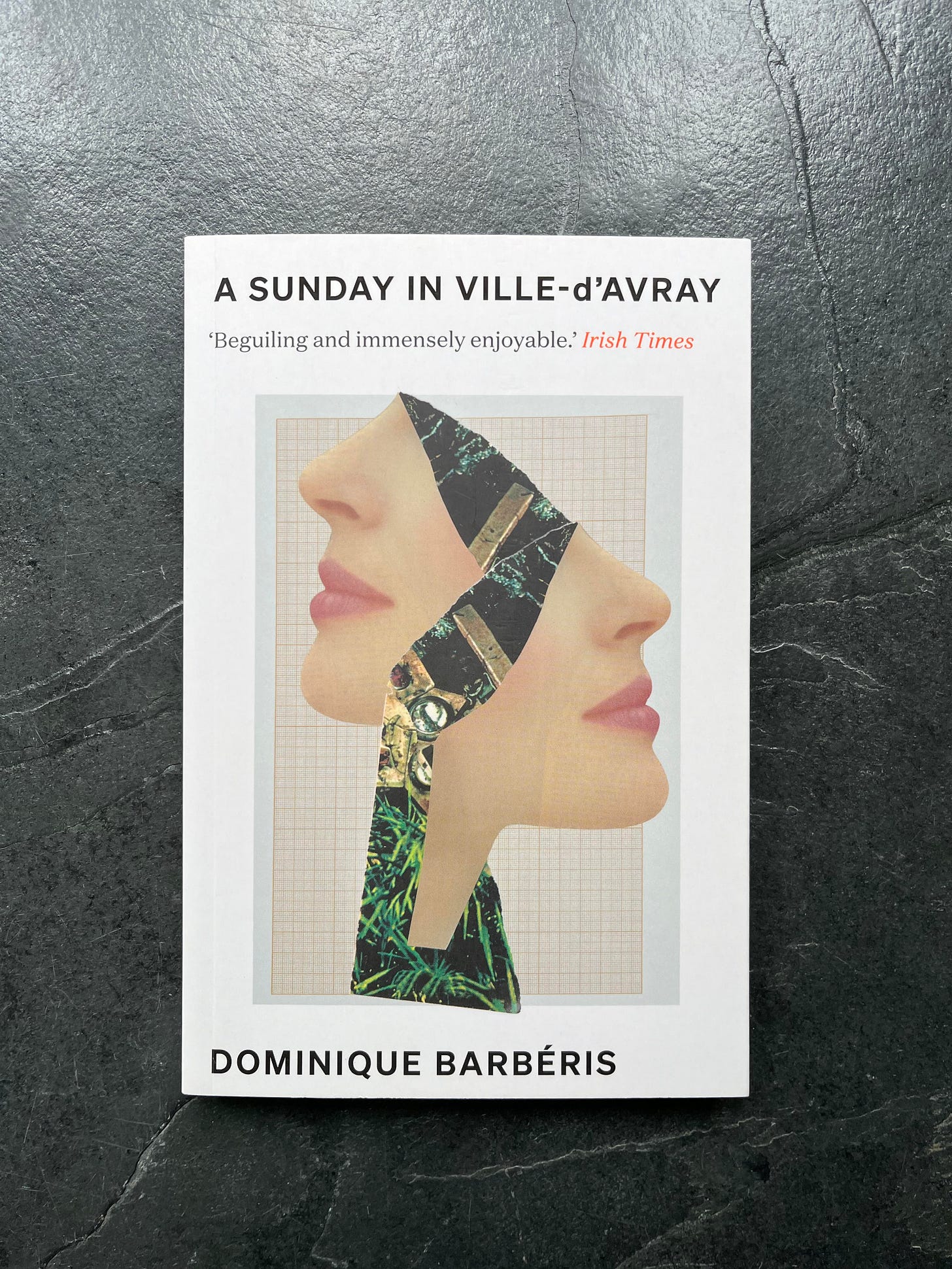

To take a break from violent governments, I decided to pick up ‘A Sunday in Ville-d’avary’ by Dominique Barbéris. On a Sunday in early September, a woman leaves muggy Paris to visit her sister in the suburbs of the city. Ville-d’avary is less than an hour away but it feels like another world. The sisters' relationship is ambiguous; Jane’s visits to Ville-d’avary leave her unsettled as Claire Marie seemingly knows exactly how to get under Jane’s skin. As they settle into the torpor of the afternoon, Claire Marie confides in Jane and tells her about a curious encounter from her past. Sundays are when she thinks about life, whether she is satisfied with how it has turned out or whether she is still waiting for it to begin. ‘A Sunday in Ville-d’avary’ is a novel about truth, and desires that can never fully be expressed.

This disquiet novel takes place across one afternoon. ‘A Sunday in Ville-d’avary’ explores the theme of longing, desire and nostalgia. Barbéris' writing is incredibly atmospheric and I read this in one sitting. The story explores the relationship of the two sisters and the disconnect between them due to their upbringing. Drenched in atmosphere, both Jane and Claire Marie are avenues for exploring feeling unsatisfied with life. Claire Marie in particular feels this sense of disappointment about her life, that she has become a repressed housewife who is terrified she has no purpose outside her husband and daughter. Claire Marie deeply fears a lack of individuality and character. She lives in a densely populated suburb, where everyone knows everything about you, and has a popular French name. Claire Marie feels as though she is living in an oppressive atmosphere of predictability and ordinary existence. She is desperate for individuality but is inherently fearful of stepping out from what she already knows; a predicament that I think exists worldwide. The desire to be different, or unique, has to exist within an element of bravery. And for some, that is too much.

Barbéris' writing was poetic and deeply readable, I really enjoyed submerging myself in this provocative novel in one sitting. The story was intriguing and left several unanswered questions about what Claire Marie confides in Jane about. ‘A Sunday in Ville-d’avary’ captivatingly explored complexities of relationships, contentment and expectation. It asks questions about paths not taken and the thrill of subconscious desire. This book is heavy on the atmosphere it brings rather than the plot line. It creates a slow burn ambiance out of the lives of two mundane sisters. I would recommend this book and call it a borrow. If you enjoy atmospheric reads that feel tense, this is definitely one for you. I think this is a great summer read.

‘War With The Newts’ by Karel Čapek was my classic novel for May. Translated from Czech, ‘War With The Newts’ is a humour allegory of twentieth-century European politics and humanity. Captain van Toch discovers a colony of Newts in Sumatra which can be taught to trade, use tools and speak. As the rest of the world learns of the creatures and their capabilities, it is clear that this new species is ripe for exploitation. They can be traded in their thousands, will do the work no human wants to do, and can fight; but the humans have given no thought to the terrible consequences of their actions.

‘War With The Newts’ was a completely captivating science fiction satire. Čapek provides profound commentary on colonialism, the ethics of scientific discovery and the consequences of playing with the nature of humanity. Written almost a hundred years ago, and still painfully relevant today, ‘War With The Newts’ speaks to humanity's relationship with power, and more specifically, the abuse of power. ‘War With The Newts’ reads like a fable on human behaviour and society, suggesting that humanity has this inherent need to exploit others. This book is a response to emerging global capitalism of the 20th century. Through the Newts, Čapek explores the process and consequences of unrestrained commercial exploitation. Čapek articulates how the exploitation of others for profit is as old as humanity; there is never a time where this hasn’t existed.

‘Don't’ you believe that each Newt represents some kind of economic value, the value of a working force that lies latent in it waiting for its exploitation’ p.137 in ‘War With The Newts’.

‘War With The Newts’ reads like a direct response to colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade, and its relevance prevails. It made me think of those enslaved to mine for cobalt in the Democratic Republic of Congo for us to have the latest technology or garment workers for fast fashion companies so people can consume clothing at an extortionately horrific rate.3 Čapek is exceptional to be able to write deeply funny, critical and scathing commentary on the continual exploitation of others that still holds up one-hundred years later.4

Along with the exploitation of others, Čapek also speaks to humanity's relationship with conflict. By taking inherently human acts, such as war, and situating them within a Newt population, Čapek is implying the absurdity of fighting over identity politics. Passages about how the Newts will evolve to become just as senseless towards each other as humanity was sobering. While reading these excerpts my mind was continuously contextualising Čapek’s words into the present day and the egregious genocide in Gaza and the war in Sudan that are happening right now. 5 Bleaky, Čapek is discussing how exploitation and violence is inherent within human nature. While you could make the case to dispute him, I’m not sure the last one-hundred years since he wrote this prove otherwise.

‘Some are living in the west, and others in the east; they might want to fight for the sake of the west against the east. Here you have the European Salamanders, and down there are the African ones; it would be the devil if ultimately some didn’t want to be better than the others! Well then, they will try to show it in the name of civilisation, expansion, or I don’t know of what: there will always be some spiritual or political reasons for which the Newts of one shore will have to cut the throats of Newts on the other.’ - p.336 in ‘War With The Newts’

‘War With The Newts’ is full of economic and political extremism that has been satirised in a timeless way. It is so clever, relevant and bleak. I wish Čapek could see what capitalism, and humanity as a whole, has evolved into today. However, I expect he would not be shocked at the continual evolving of humanity's boundless greed. There are no limitations to the bigotry and thoughtlessness that capitalism encourages. I loved this book and I was so impressed with how timeless the discussion around humanity was. I would absolutely recommend this and call it a buy. ‘War With The Newts’ is for anyone who enjoys science fiction and/or existentialism and commentary on human nature. It was a deeply thought provoking read and an incredibly accessible classic.

‘What Is Mine’ by José Henrique Bortoluci. A memoir exploring the intersection of personal and national histories, ‘What Is Mine’ is about Bortoluci’s father. From the mid-1960s to the mid-2010s Bortoluci’s father, Didi, was a truck driver in Brazil. His work took him away from home for long stretches at a time as he travelled and participated in huge infrastructure projects. Didi was involved in the Trans-Amazonian Highway which was spearheaded by the military dictatorship of the time and undertaken thanks to brutal deforestation. Didi recounts the toll his work has taken on his health, from heart-attacks to a cancer diagnosis, which has defined his retirement. By weaving the history of the nation with Didi’s life on the road, Bortoluci explores the similarities between cancer and capitalism which both embody the sentiments of ‘the gospel of growth at any cost’.

‘How do you narrate the life of an ordinary man?’ p.24 in ‘What Is Mine’

‘What Is Mine’ is an exceptionally beautiful memoir that situates the history of a nation within the individual. Bortoluci creates an oral history of Brazil through Didi’s life on the road, exploring how he felt witnessing such huge change in the country. Bortoluci contextualises his fathers lived experience into the socio-political theory about Brazil he has encountered as an academic. Through Didi’s interviews we are able to understand the intersection between class, poverty and immigration that have made up the nation's landscape. Didi recalls witnessing the beginning of the mass deforestation of the Amazon and the prolific impact this destruction had on the lives of those who lived within and around it.

While ‘What Is Mine’ is an impressive account of the history of Brazil through the lens of an ordinary man, it is also a memoir about labour. Bortoluci explores the complex relationship between class and identity. He discusses the financial promise of being a truck driver, positioned as an opportunity for people to gain homes, businesses and possibly financial freedom; but this is something that rarely materialises. ‘What Is Mine’ takes a look at the labour Didi and his peers put into the development of the nation by transporting goods and services, and keeping the country going, with little financial security.

Bortoluci boldly relates illness to autonomy and power, linking his fathers cancer diagnosis in relation to the nation. Didi’s cancer diagnosis encourages Bortoluci to explore the landscape of sickness and consider how Didi traded his health for the progress of the nation. As the last one left among his trucker peers, Didi is again an example of the impact of the exploitation of the workforce. I thought the exploration of the intersection between illness, capitalism and the sociopolitical state of Brazil today was highly nuanced and I was incredibly impressed;

‘The political and social devastation we have lived through in recent years has its origins in the long history of Brazilian authoritarianism. Destruction became the state’s official policy, the official aesthetic one of coarseness, sophisticated ideas a reason for persecution. Our illness, in its most recent guise, turns places of gloom into motives of national pride: the sawmills in the middle of the forest, the torture centres, the alleyways where death squads operate, [...] These become the ethical models, the aesthetic references and the libidinal motors of a new cartography of destruction’ p.115 in ‘What Is Mine’

‘What Is Mine’ is an incredibly fascinating, engrossing and emotional novel about father and son. Bortoluci has written a moving and wonderful intersection of personal and national history. Anecdotes from ordinary people are so essential to understanding the fabric of a nation and its history. Didi’s oral retellings of his experiences as a truck driver bring to life the last fifty-years of Brazil’s history in a way that no socio-political commentary ever could. I couldn’t recommend this enough and would call it a buy. I loved it.

Thank you so much to Fitzcarraldo Editions for this ARC

‘Ti Amo’ by Hanne Ørstavik tells the complex story of love and mortality. Our unnamed protagonist is a woman who is in a deep, loving but new relationship with a man. She has moved to Milan to be with him, they are married and are unbelievably close in every way. He is diagnosed with cancer but they try to go about their lives as best as they can. One day she asks the doctor how long her husband has left to live - and he says that he has less than a year. Instructed to not tell her husband, death inevitably comes between them. She knows it's coming, but he doesn’t wish to know.

I’m not sure why I have gravitated to so many books about death and illness in the past few months but here we are. ‘Ti Amo’, which translates to ‘I love you’, is an incredibly beautiful and harrowing novella about illness and relationships. Ørstavik explores the incredibly complex emotional landscape of love and illness and the relationship between the two. In a relatively limited word count, Ørstavik delves into bereavement and asks how do we live when the one we love the most is about to die.

I think the experience of reading this book will hinge deeply on the reader's relationship with long term illness and grief. I thought Ørstavik did an exceptional job of articulating the arrival of a chronic or terminal illness within a relationship. You have to make space for a third party - it is no longer just the two of you. The landscape of love dramatically changes when long term illness comes into play. Ørstavik explores the partner to caretaker pipeline that exists within the chronic and terminal illness community, as well as the sorrow that is felt in the face of such an enormous loss of control. Ørstavik eloquently articulates the conflict between love and illness. How something that feels as powerful as love and connection is in direct conflict with illness; because love cannot change that reality, and that is really hard to accept. ‘Ti Amo’ explores the liminal space that illness puts you in, about the relationship you form with waiting and being at the whims of illness.

I read ‘Ti Amo’ in one sitting and I’d recommend that reading experience to get the most out of this emotional novella. Ørstavik skilfully submerges us into a beautiful and painful relationship that honestly explores love. It came as no surprise to me when I read that ‘Ti Amo’ is an auto-fiction about Ørstavik losing her husband. Poignant and touching ‘Ti Amo’ reads like a love letter to her husband, and herself. It reads as a permission to start grieving before the end when the knowledge of death is so present. It investigates when the grieving begins for those who are left behind; is it before the diagnosis, during sickness or only in death? Ørstavik accurately suggests that grieving someone who is unwell starts long before they actually die. I’d recommend ‘Ti Amo’ for anyone who wants to feel sad and would call it a borrow.

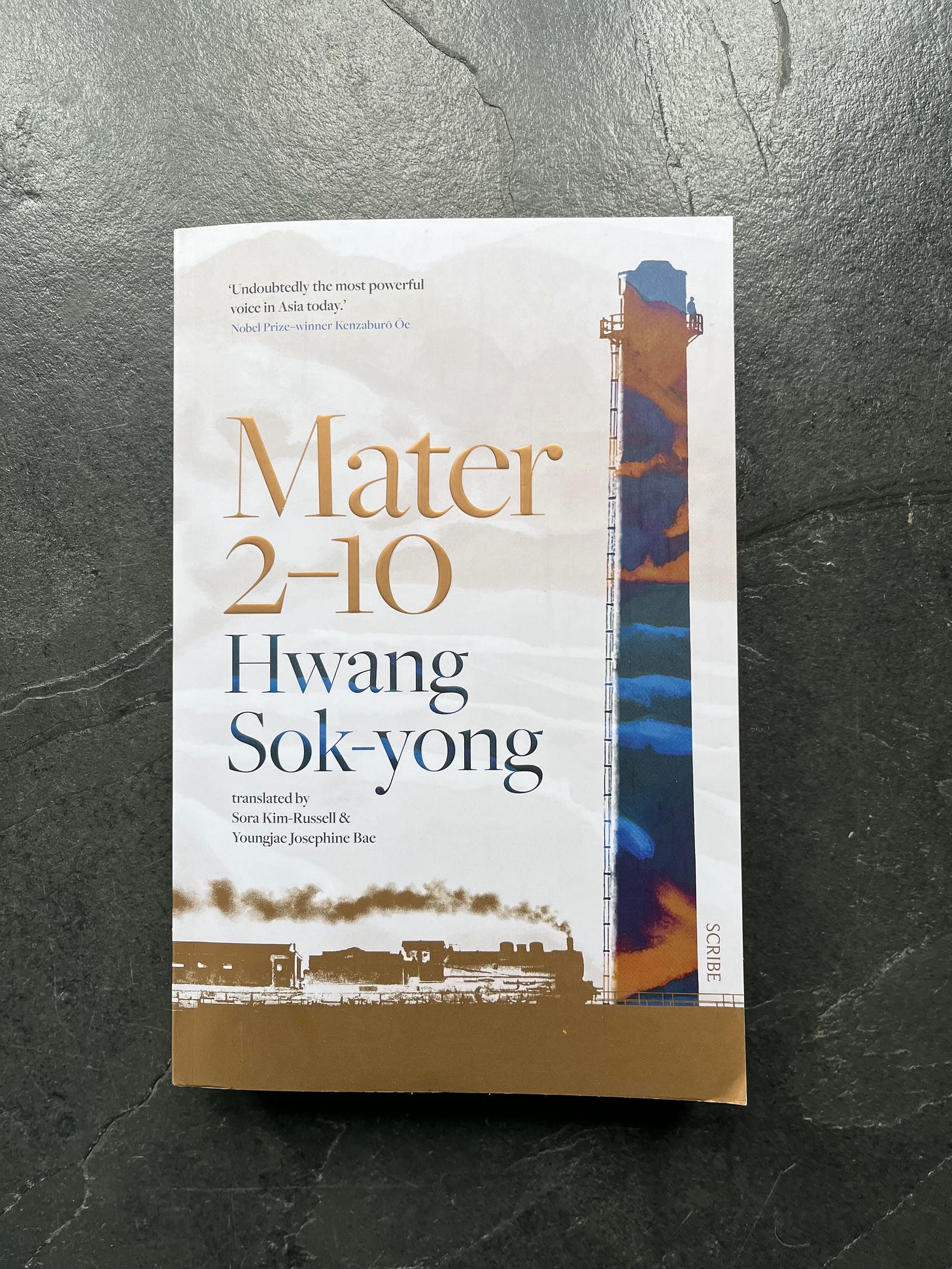

‘Mater 2-10’ by Hwang Sok-yong was the final book I had left to read from the International Booker Prize shortlist. In contemporary Seoul, a laid-off worker stages a months-long sit-in atop a sixteen-story factory chimney. During the long and lonely nights, he talks to his ancestors, contemplating on the meaning of life and wisdom passed down the generations. Through the lives of these ancestors, three generations of railroad workers portray the struggles of ordinary Koreans - starting off in the Japanese colonial era, continuing through Liberation and right up to the twenty-first-century. ‘Mater 2-10’ is an account of a nation's longing to be free from oppression and explores the blood, sweat and tears shed by modern industrial labourers.

‘Mater 2-10’ included, in exceptional detail, the history of the workforce in Korea and the abuse they suffered across almost the entirety of the twentieth century. While this detail is ultimately what pivoted this book from feeling like historical fiction to non-fiction, the discussion around the history was exceptional. Through the ancestors within the story, Sok-yong details the experiences of ordinary working class Koreans and how much adversity they faced. From Japanese colonial rule up to the division of into North and South regions, workers in Korea have been exploited. ‘Mater 2-10’ details how the development of Korea as a nation, specifically in regard to the railroad, was down to the labour of ordinary Koreans who were underpaid and exploited. He argues that this aspect of Korean history is not recognised and often overlooked.

‘Mater 2-10’ is also a story about revolution and growing political consciousness. As the workers continued to be exploited, a growing political affinity spread amongst the workforce. In particular, the understanding of communism and interest in workers rights unions. The present day protagonist is also, still, protesting for workers rights as Sok-yong articulates that the relationship between labour and the government in Korea hasn’t changed much, despite some of the absolutely enormous changes that have taken place within the country over the last century.

While at points the exploration of these two themes were deeply interesting and captivating within the story, ultimately the intensity of historical information pushed ‘Mater 2-10’ into a non-fiction realm. Often the story read more like the history of workers rights in Korea (which is deeply interesting) rather than historical fiction. For me, there was a missing emotional investment within the storyline. I learnt so much I previously didn’t know about Korea and I did enjoy that aspect. However, from the standpoint of emotive storytelling ability, I found this didn’t quite work. The elements were there for this to be a great historical fiction, but ultimately it didn't deliver. It faltered in keeping the storyline tight, which interfered with developing an emotional investment within the protagonist. Narratively, the protagonists present day protests felt like they were disrupting the ancestors storyline.

I am aware that perhaps the translation could have had an effect on this, impacting the flow of language and delivery of the storyline. The translators spoke of the concern they felt while translating, not wanting to whitewash Korean history and culture but simultaneously having to make decisions about what to preserve and what to change for the best translation into English.6 This is always an added aspect when reading translated literature, understanding how the translation adds, or perhaps takes away, from what the author intended. While I am deeply aware of the nuance of translated literature, and potentially I do think it may have been the translation that let this down (and I unfortunately cannot read Korean), I ultimately wouldn’t recommend ‘Mater 2-10’.

If you have an interest in learning more about the history of the workforce and labour within Korea, I would absolutely recommend you read this. I think if you approached this anticipating more of a non-fiction narrative, you would get more out of the novel. However from a purely fiction standpoint, I don’t think it holds up well. It slightly hurts me to say this, but I would call ‘Mater 2-10’ a bust. What it did remind me of was ‘Whale’ by Cheon Myeong-Kwan which I read last year and thoroughly enjoyed and would recommend. They share themes of exploring the voiceless figures of Korean history and explore this with a lot of magical realism. It also made me think of ‘Pachinko’ by Min Jin Lee which does hold up as a generational historical narrative of a Korean family and the quest for freedom.

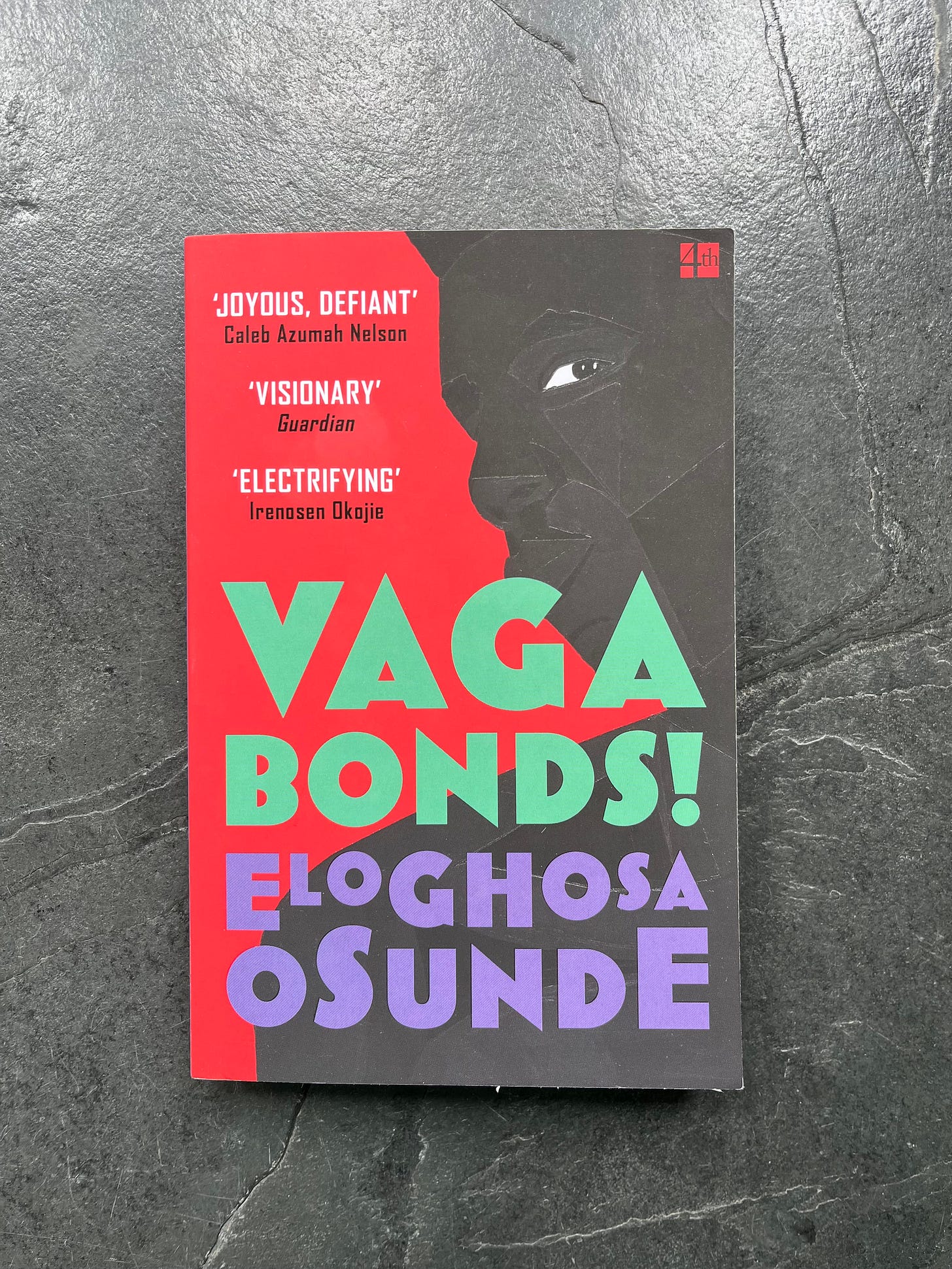

‘Vagabonds!’ by Eloghosa Osunde. Eko is the spirit of Lagos, and with his loyal minion Tatafo, they weave trouble into the lives of the ‘vagabonds’ in modern Nigeria: the queer, displaced and footloose. With Tatafo as our guide we meet these people living in the shadows. Among them are a driver for a debauched politician; a lesbian couple whose relationship sheds unexpected light on their experience with underground sex work and a mother who attends a secret spiritual gathering that shifts her reality. As their lives begin to intertwine, the vagabonds are seized and challenged by the spirits who command the city. A force seems to be drawing them all together, but for what purpose?

Situated within the world of Nigerian folklore, ‘Vagabonds!’ explores love, identity and resilience. This was an incredibly unique narrative, unlike one I have ever encountered before. While ‘Vagabonds!’ is not described as short stories, I would suggest that that is how the novel reads. The writing reads like a selection of short stories that are threaded together by the presence of the spirits, rather than a continuous narrative. Osunde’s writing was, at times, so lyrical and gorgeous, creating quite exceptional character development and emotional investment in such few pages. Unfortunately, at other times it felt stilted and I struggled to feel connected to the plot, or lack thereof. As the stories of some of these characters closed I felt, quite frankly, desperate for more and wished they weren't such brief snapshots.

‘Vagabonds!’ was Osunde’s debut and at times it felt unrefined. There was a lot of really exceptional writing in here, but it felt like the structure of the narrative let it down. Conceptually, ‘Vagabonds!’ reminded me of ‘Lakiriboto’ by Ayodele Olofintuade and ‘Dazzling’ by Chikodili Emelumadu. I think ‘Lakiriboto’ achieves what ‘Vagabonds!’ didn’t, which is an incredibly compelling story about the experience of the LGBTQIA+ community in Nigeria’s landscape of corruption. I enjoy vignettes and short story narratives so I am surprised this didn’t work for me. Something felt missing - arguably a stronger editor.

I absolutely am looking forward to reading whatever Osunde writes next and I don’t regret reading this. I’d call ‘Vagabonds!’ a borrow. I know several people who really loved this, so perhaps my expectations were too high. I would recommend ‘Lakiriboto’ over this though if you’re looking for a read that tackles a relationship between folklore and LGBTQIA+ in modern day Nigeria.

And that concludes my May Reads! My favourite reads this month were ‘Cantoras’ and ‘What Is Mine’.

My first read of June is also my classic for the month; ‘East of Eden’ by John Steinbeck. I am reading alongside my fellow newsletter peer

. I am looking forward to tackling this formidable classic with a friend. If you love East of Eden, you might want to click here.There are no extras from me today! The only thing I have to comment on is that Kairos won the International Booker Prize. If you read my April Reads, you’ll know how I feel about that. I really don’t recommend you read Kairos - read, quite literally, anything else.

Let me know your thoughts:

❀ What have you read and enjoyed in May?

✮ Have you read any of these books? What did you think?

✿ What are your summer reading plans?! Share any and every book you are planning to read this summer! My go to summer reading recommendation, incase you’re looking for one, is always ‘Swimming In The Dark’ by Tomasz Jedrowski

❊ Do you have any recommendations for me based off of the themes from this month?

Thank you, as always, for reading. Please let me know if you found a book or two you’d like to read!

See you next month,

Happy Reading! Love Martha

If you know someone who loves books, share this newsletter with them!

Catch up on what you might have missed:

Before you go - if you enjoyed this, why not subscribe? <3

okay love you bye !

‘Simple justice’ he said. ‘Not murder-murder’ from p.147 in ‘Some People Just Need Killing’ by Patricia Evangelista

‘when individual liberty gives way to encouraged state brutality’ quote from p.310 in ‘Some People Just Need Killing’ by Patricia Evangelista

This link if you don’t know what I am talking about when I mention the DRC: https://www.amnesty.org.uk/press-releases/dr-congo-huge-expansion-cobalt-and-copper-mining-wrecking-lives-new-report and this for fast fashion facts which you should frankly already know: https://goodonyou.eco/exploitation-in-the-fashion-industry/

In general I think its useful to link reports like this all the time: https://www.walkfree.org/global-slavery-index/findings/global-findings/ - I was reading this when I was writing this newsletter and I think it’s a failure to not consistently remind everyone that slavery didn’t end with the transatlantic slave trade! And because I mention enslavement & exploitation A LOT in this review I thought it would be a disservice to not give you the opportunity to familiarise yourself with the specifics/facts more.

Me again with more links to the hideous things that are happening all over the world right now! https://www.chathamhouse.org/publications/the-world-today/2024-02/sudan-collapsing-heres-how-stop-it - this link is fantastic for detailing & explaining what is happening in Sudan right now.

This discussion between the translators can be found within p.x in ‘Translators Note’ within ‘Mater 2-10’

Vagabonds has been looking at me from my shelf for a while and I definitely need to read! Cantoras sounds so good and I need to pick up the newts book,

it sounds so so good. as always, an interesting list!!

Thank you for another stupendous range of books to read!