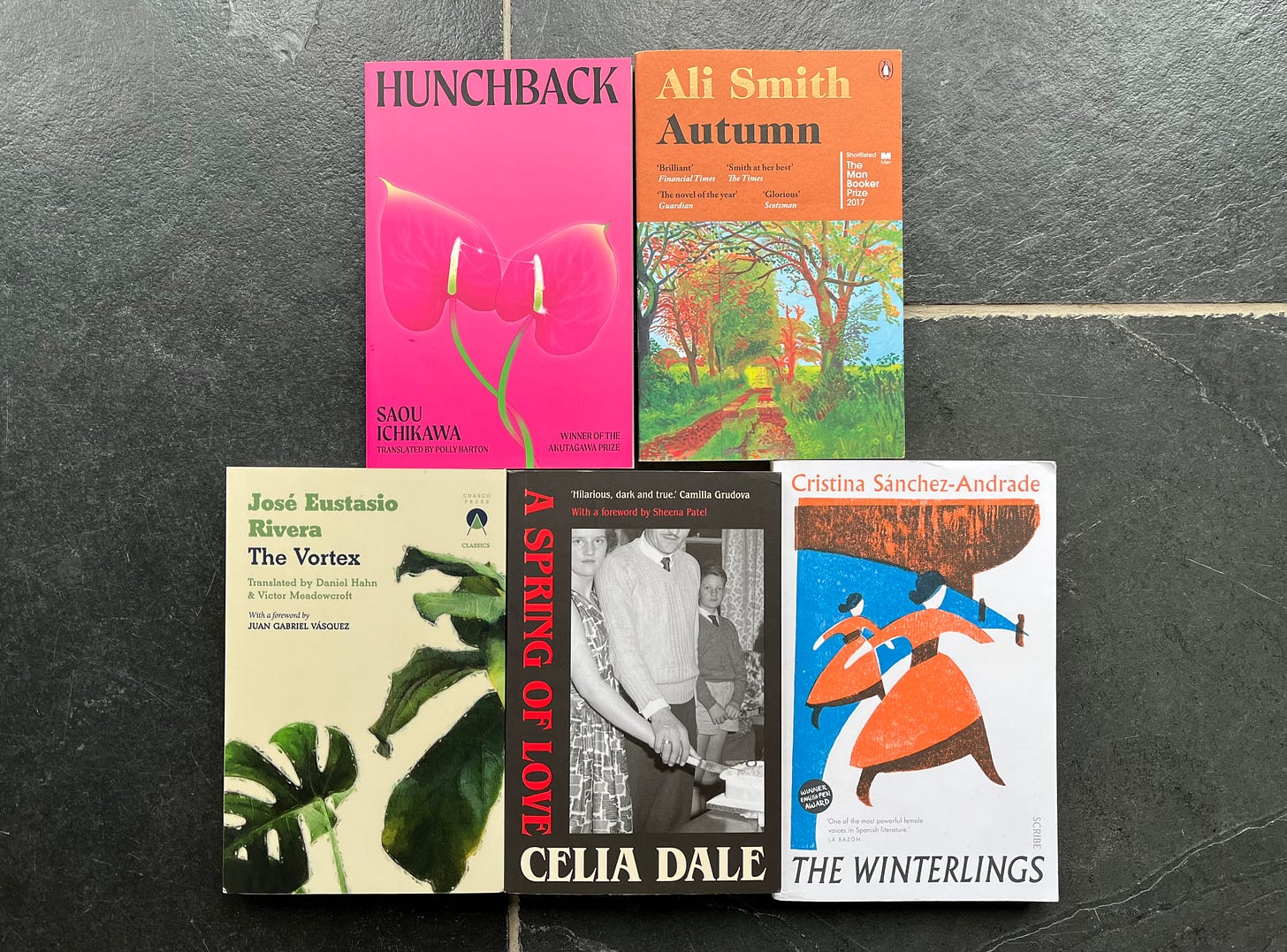

Happy New Year readers! Welcome to my last monthly reads of 2024. December was a busy life month and subsequently a quiet reading month. I have to say, doing a flat lay of only five books felt very bizarre.

These books all explored protagonists who live in isolation, separated from society. When something happens in each of their lives, they find themselves navigating an unknown territory. Whether literally, like in the Colombian jungle, or emotionally, like having a relationship for the first time, each book follows characters who are in search of something in the unfamiliar.

To see the translated reads from December on Martha’s Map, including authors from Japan, Spain and Colombia, click here.

For those who are new, buy, borrow, bust is my recommendation key: Buy = I loved this book and highly recommend it. Borrow = I liked this book and think it is worth a read. Bust = I wouldn’t recommend this book from my reading experience.

‘A Spring of Love’ by Celia Dale

This novel is like a time capsule, transporting us back to the 1950s where gender dynamics and life under the patriarchy was much more sinister. A Spring of Love tells a story that is so mundane, it is actually unsettling. Esther, our protagonist, is a morally robust and determined woman. Single, thirty and fiercely independent; she goes to work and is a landlord of two properties thanks to her late grandfather. Her life is quiet and small, governed by regular routines established over years of repetition. There is a comfortable harmony to how she conducts her day to day life. With multiple streams of income and no one to consider, except her grandmother, Esther’s life is her own. A circumstance that present day readers would greatly admire. But everything changes when she meets Raymond.

One day, Raymond chooses to sit opposite her in the diner she frequents every Thursday. Alarmed but maintaining politeness, Esther allows him to accompany her. From that day forward, Raymond begins to show up everywhere. He opens this chasm in Esther that she didn’t know was there about all she has missed and is missing because she had never had a man;

‘It was as though until now she had wilfully blinkered herself against living humanity because she was afraid that to look at it would hurt her. She had thought she was content, a woman without much need for love, envying no one, desiring nothing; now she stared about her hungrily, amazed by the joy of possessing what she had not known she lacked’ p.78 in A Spring of Love

When Raymond asks Esther to marry her, she believes she has never felt more alive. But every change in Raymond's eyes is a hint at the truth about the man he really is. He slowly begins to assert more possession and control, and we are left questioning: can Esther see what is right in front of her, or is she blinded by the life she feels she ought to have?

Dale is subtle in her exploration of the confinements of a patriarchal and heteronormative society. They are not lamented as concepts, but embedded within every character on the page in different ways. She explores the mundane civility of British suburbia through the quiet hours spent at home. Dale questions what the currency of marriage and motherhood is under the patriarchy and what is gained, or lost, when they are absent from a woman's life? Dale was ahead of her time in the way she questioned the value of a woman's life based on her romantic relationships with men. We are made to question if Esther is falling madly in love with Raymond because she loves him, or because a woman cannot be accepted in society unless she is in a long-term relationship?

A Spring of Love is subtle in its sinister energy, but when the tone becomes menacing, it is alarming. Dale delivers these lines from some of the male characters which are filled with vitriol and misogyny, and everything starts to feel horrifyingly precarious;

‘I tell you people are rotten, rotten and selfish right through [...] And women is the worst. A woman wants something and it don’t matter what’s in the way, she’s got to have it. [...] They don’t care about nothing else, they’ll lie and cheat - all they want’s a good time. They think of nothing else but men, men, men, morning, noon and night. That's the only thing they want. [...] Animals they are, animals on heat’ p.142-3 in A Spring of Love

I thought this book was incredible. I had almost no expectations before reading it, and found myself completely taken by the story. At the beginning, it feels as though Esther and the reader are both wary of Raymond. Esther’s characterisation is exceptional and we feel like her outlook on life is unshakeable. But as the book progresses, the reader is being left behind by Esther, and we watch her become more enthralled with the status she has gained by becoming a wife. A Spring of Love explores the unknowability of people as Esther becomes someone we don’t recognise.

A Spring of Love is full of depth, nuance and was a joy to read. I have done my best to maintain as much mystery as I can here because I think this novel is best to go into knowing nothing. This was my first Dale and I am incredibly interested in reading more of her work. She has written perhaps one of the most eerie and emotionally complex novels I have ever read. I absolutely recommend this and call it a buy. This was wonderfully different to anything I have read for a while and I loved it. I think this could be enjoyed by many of you - so I look forward to hearing if anyone decides to pick it up!

‘Autumn’ by Ali Smith is a meditation on the unlikely friendship between Elisabeth and Daniel. Set in the summer of 2016 in the United Kingdom, an episodic narrative alternates between Elisabeth’s childhood in the 90s, when she first meets Daniel, to the present day where she is visiting him in a coma. The narrative reflects on the commencement of their relationship which occurred because Elisabeth’s mother asked her neighbour to babysit. What followed was an unexpected friendship of curiosity and conversation. It is evident Elisabeth feels some sort of intellectual superiority towards her mother, and an affinity with Daniel. This affinity has characterised Elisabeth’s life, always holding Daniel in admiration. There is a frequent misunderstanding that he is her grandfather, but she never corrects them. Her frequent visiting of his bedside is full of love and longing as she reads to him.

2016 was a landmark summer in the UK, I remember it well, where the Brexit vote took place and it was devastating. We follow Elisabeth as she experiences this hopelessness in a life of mundanity, ruminating on her past and future. In many of her childhood memories, Daniel is there. A hundred-years-old, he exists as this bridge across time. While her future feels insecure, there is this sense that her friendship with Daniel has always been dependable. With Daniel in a coma and Brexit vote signalling immense change in Elisabeth’s life, Smith writes a meditation on an unlikely connection in a summer of upheaval.

I have read an Ali Smith before this, How To Be Both, and I quite frankly hated it. I thought that perhaps my hatred could have been an exception, that I should give Smith another go. Unfortunately, I think it is safe to say, I do just hate Smith’s writing. I found Autumn to be exceedingly boring and nonsensical. I thought the friendship between Elisabeth and Daniel was a lovely relationship to explore, but the way Smith approaches and structures her novels meant that this relationship was almost impossible to follow. Her prose constantly veered away from the focus of this relationship into experimental passages about the passing of time and the surrealist point-of-view of Daniel in a coma. While I welcome the exploration of these themes, Smith pieces them together in a way I just could not follow. The friendship is hanging on by the faintest of threads as the book intertwines incoherent and vague rumination throughout that, even if my life depended on it, I could not describe.

Daniel’s coma and the Brexit vote both characterise this fracture in time. Both events represent cycles coming to an end, and a new beginning. The combining of these themes felt anticipatorily poignant, but in reality they felt fleetingly dull. Talking about Autumn in The Guardian, Smith said to ‘Always look to story for the real plot. Look to dialogue always, for the life’ and I wish I could. I wish I could see the life she has set out to embed in the dialogue, the ‘real’ plot that exists within this narrative. But I can’t. For me, there is no life in her dialogue; it is shallow and stilted, a life devoid of humanity and compassion. While I may not understand Autumn, I know this is not what Smith intended.

I love the pretence of this book; an exploration of an unlikely connection is something I am all for. However, I just cannot understand Smith’s style or feel moved by it. I saw the NYT describe Smith’s writing in Autumn as ‘fearless’ and ‘non-linear’ - and I agree in much less complementary tones. Autumn is non-linear and fearless in the sense that Smith has written one of the most meaningless books I have ever come across. I found Autumn’s complete lack of direction to be unbearable.

Non linear and reflective narratives that ruminate on life's big questions are books I enjoy, so my lack of chemistry with Smith’s prose will remain a mystery to me. I think it is a combination of the fractured narrative and indirect prose. A friend said to me that Autumn would be an impressive book to study, but is not an impressive book to read for pleasure, and I agree. I do not recommend this at all and would call it a bust. If anyone loved Autumn, or Smith in general, I’d love to hear why! I’d appreciate a case on why her writing is wonderful. I admire what she was trying to do with this novel, and the rest of the quartet I’m sure, but I did not enjoy it one bit.

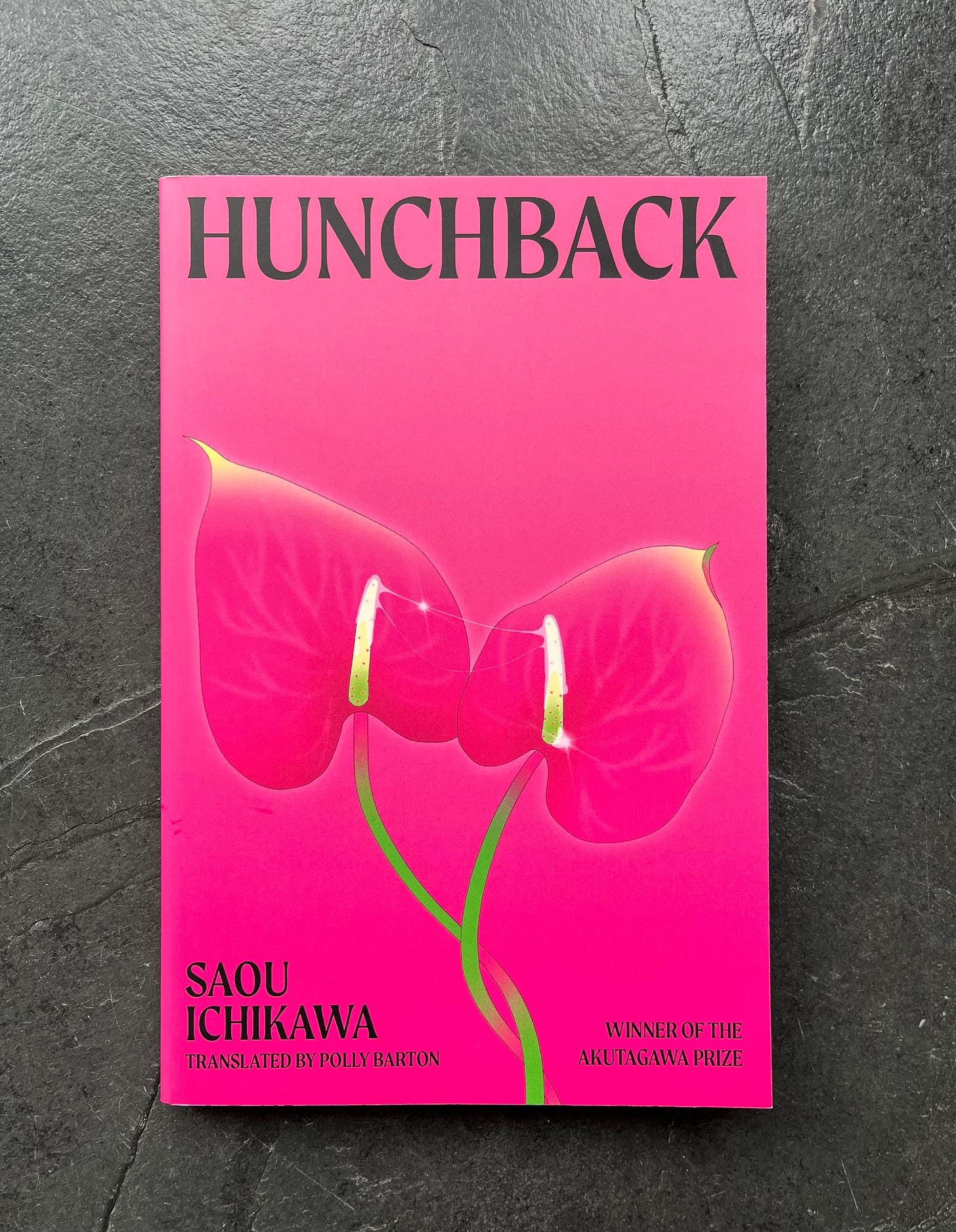

‘Hunchback’ by Saou Ichikawa is the story of a very wealthy and disabled woman called Shaka Isawa. Shaka uses an electric wheelchair and ventilator because she was born with a congenital muscle disorder. She lives in a care home where she is extremely well looked after because of the financial agency and power she has inherited from her parents. Living with so many physical limitations, Shaka lives out much of her life on the internet. She enrols in classes, writes erotic flash fiction and uses twitter like a personal diary to imagine a life without limitations;

‘In another life, I’d like to work as a high-class prostitute.’

‘I’d have like to try working in McDonalds’

‘I’d have like to see what it was like to be a high school student’

‘If I wasn’t disabled, the world would have been my oyster…whatever that means’ p.8 in Hunchback

A life spent in an electric wheelchair and a 24 hour care facility, Shaka has always existed outside the realm of visibility. She does not consider that anyone could be reading her tweets or the outrageously erotic stories she writes. Until one day a new male carer reveals he has read it all. After initially feeling very vulnerable, Shaka views this as a possibility. So she makes him a proposal, one that could help facilitate one of her many desires.

Hunchback is a novella about disability, power and sex in an able-bodied society. Sex and power are not themes often explored or associated with disability. We rarely, if ever, read a protagonist who is a disabled woman expressing sexual desires. Disabled people, particularly women, are not perceived as sexual beings because sex is seen as an able bodied, heterosexual and penetrative activity. Hunchback explores power in the relationship between money and disability. The agency financial autonomy can give someone who, in an able bodied society, is often deemed to have none. Ichikawa defiantly explores the limitations our society puts on disabled people, challenging perceptions of disability and power.

Both sexual and financial exploration occur in Hunchback, but it is never quite clear who is the abuser and who is the abused. We are confronted with a complex and unsettling web of assumptions and stereotypes. It is evident that Ichikawa wanted to anticipate and resist the reader's automatic assumption that Shaka is in a position of no agency because she is disabled. Ichikawa challenges the narratives that pervade our able bodied society; the damaging assumption that disabled people are always good victims who do not experience complex emotions like sexual desire and abusing their power.

Hunchback is an explosive novella about a disabled woman whose existence challenges all of these stereotypes. This novella is in many ways confronting as Ichikawa challenges the reader's perception of disability to entertain associating these themes with an disabled woman of colour instead of an able bodied white man. Ichikawa says disabled people are people too - people who can participate in society and do not need your ‘pity’. Ichikawa’s writing is matter-of-fact as she honestly describes an existence that is complex and politicised.

I liked the format choice of a novella for Hunchback, I don't think the story could have supported any more pages. While there were some artistic choices that I didn’t love, Hunchback excels in asking big questions about our society and humanity; the prejudices and assumptions society holds about disability. It makes you consider the multifaceted sides of agency and life as a disabled person. It asks; What defines participating in society? Who is allowed to have desires?

The plot is dark and twisted, and might make the reader want to look away. To which I think Ichikawa asks why? Is it because you can’t work out who is being exploited or decipher who has the power? Hunchback is challenging and makes disability extremely visible. This novella is radical and unsettling. Ichikawa has written a semi-autobiographical novella about the power of storytelling and disability. Within it all, she also manages to discuss reproductive rights, eugenics and the exclusionary practices and ableism of the publishing industry. I would recommend this and call it a borrow. Disabled voices are hard to come by within translated fiction, so Hunchback was a first for me and I hope there are many more to come.

‘The Winterlings’ by Cristina Sánchez-Andrade tells a strange and fascinating fable about our relationship to the past. We follow two sisters, Dolores and Saladina, as they return to the isolated and insular parish of Tierra de Chá in Galicia. It is where they grew up, but were sent away to spend a childhood in exile in England during the Spanish Civil War. Upon their return, they see that nothing has changed from the people to the customs. They return to their grandfather's house, who died while they were away, but they do not know the circumstances of his death. Their return brings wounds to the surface about the ghosts that remain after the war. The villagers do not know why the sisters have returned and they begin to panic. There is a sense of foreboding as we begin to understand the entire ecosystem of this village is maintained by secrets and lies, a very delicate balance that a pair of outsiders could break.

Every character within the village is known by their exaggerated characteristics instead of their names. This exuberant dehumanisation is something that pervades throughout, seemingly little is known about anyone. This absurd characterisation is extended to the sisters, who become referred to as ‘The Winterlings’. It becomes clear that secrets and rumours are an essential part of the fabric, and history, of this village. With the fear that the repercussions of human actions can re emerge at any time, the vagueness of what is real, and what is not, is intoxicating to read. The strangeness of this novel completely drives the plot as we read feverishly to work out what actually happened in those years when the Winterlings were in exile?

The Winterlings takes place in the 1950s, around a decade after the civil war ended. While this novel is not a direct discussion about the aftermath of the war, the conflict's history is embedded in the fantastical tale. The whole parish knows what happened to the Winterling’s grandfather, they were involved in his fate, but wish to keep this a secret. They feel shame and guilt in remembering the past, not wanting to be reminded of how the war forced friends and family to inform on each other in order to stay alive. This shame in Tierra de Chá is what drives their hostility towards the sisters. This subtle and nuanced social commentary on the longstanding domestic impact of the Spanish civil war on families and communities reminded me of ‘The Time of Cherries’. Both novels explore protagonists who return to Spain after years away to find communities and families who are plagued by secrets and shame about what happened in the war and under Franco’s dictatorship. They explore the fallout of war and oppression within the mundane; specifically relationships.

This is a novel for those who love strange books. There is little explanation about the plot and how it develops. Instead, it is an exploration of two strange sisters in a strange parish that is haunted by its past. It is funny, poetic and beautifully simple in its prose. Sánchez-Andrade has written a thought provoking contemplation on what it means to go back and understand all that has happened. She explores the bonds and impenetrable nature of isolated communities. Instead of the fighting on the battlefield, The Winterlings meditates on the weapons of secrets and lies that were employed by communities to keep them alive. Can places like the parish of Tierra da Chá ever move on, or will they always be stuck in the past?

I enjoyed the fast-paced and engrossing nature of reading this. The Winterlings is all about reading between the lines to find the real story underneath, an act of reading I love (except when reading Autumn). A deeply weird and surprisingly complex story about our relationship to the past, I would call The Winterlings a buy! I did not expect to love this novel as much as I did. I was truly enamoured by the weird and wonderful world of Tierra da Chá and the sisters' relationship. I recommend this novel for those who are curious in the exploration of confronting the past, the mysterious forces that move us and the power of talking versus not talking.

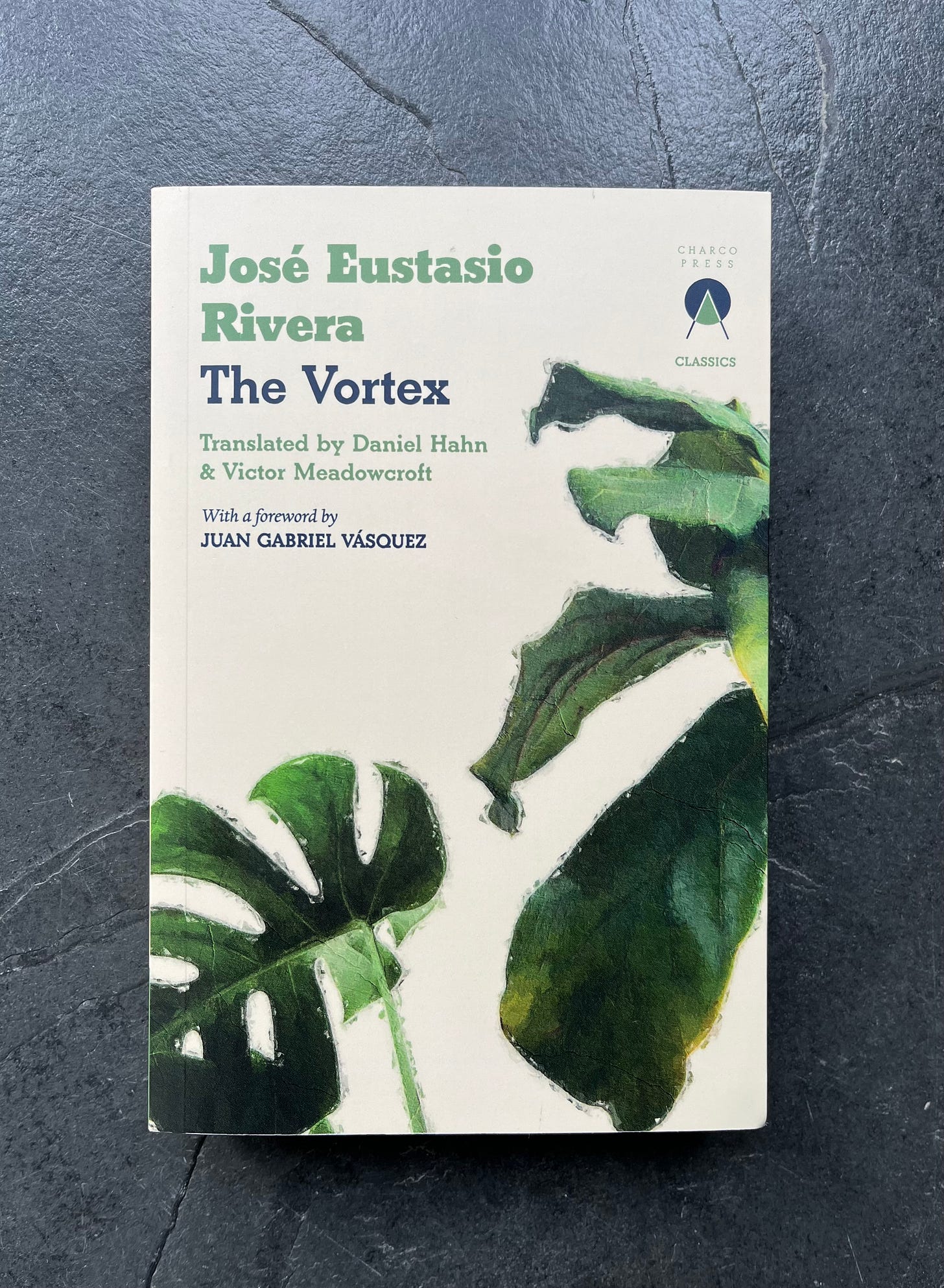

‘The Vortex’ by José Eustasio Rivera follows young poet Arutro Cova and his lover, Alicia, as they elope from Bogotá and set off on an adventure through Colombia’s varied and rich landscape. When Alicia - who is pregnant, jealous and fed up with Arturo's arrogant character - disappears, Arturo is determined to follow her and win her back. Through dense rainforests, cattle ranches and a variety of magically intoxicating landscapes, Arturo pursues Alicia. In doing so, he becomes an inadvertent witness to the horrific conditions suffered by workers forced or tricked into tapping rubber trees.

The Vortex opens;

‘Before ever falling in love with any woman, I had already gambled my heart and it was violence that won it’ p.7 in The Vortex

Which sets the tone for our protagonist, Arturo, who seemingly cannot decide what he loves more; violence or women. This is, more or less, the tone of the novel throughout. Arturo is an insufferably misogynistic man who believes that all women should fall at his feet, that they should be so lucky to know him. This arrogance is what propels him to trek across the wilderness of Colombia, confident he will succeed and all will be well. The landscape is harsh and oppressive, not easy to traverse, but Arturo’s biggest discovery was the human right abuses that were taking place during the Amazonian rubber boom of the early twentieth-century.

The Vortex introduces us to a version of the Amazon rainforest, a paradise turned upside down by human exploitation and extraction. I had never read anything about rubber tapping before; the practice of it or the slavery and exploitation that surrounds it. The lived experience of those who were brutally trapped in rubber tapping slavery were explored in part two and I thoroughly enjoyed learning about this part of Colombian history;

‘The workforce is made up, for the most part, of natives and enlistees, who, according to the laws of the region, cannot change owner until two years have passed. Each individual has an account to which the bits and pieces they’re advanced are charged - tools, rations - and against which rubber is credited at a derisory price set by the master. No rubber tapper ever learns the cost of what he receives or how much he is credited for what he delivers, because the boss’s eye is fixed on maintaining the model of always being the creditor. This new form of slavery extends beyond a man's life, and can be passed on to his heirs' p. 177 in The Vortex

To me, this novel walks the line between fiction and a nonfiction book. Long readers of this newsletter will know by now how often I reach for fiction books where I can learn, and The Vortex was no less. Rivera explores the cruelty of man in the most horrific way through the themes of civilisation and barbarism. This book is a time capsule into Colombian history; a vortex into another world, I was completely transported. It explores the environmental costs of extractive human systems and the boundlessness of human greed.

Despite my praise, to which there is plenty, the act of reading this book came with its challenges. The prose is convoluted, with perspectives often changing with no discernible distinction, making the narrative hard to follow. The Vortex frequently consisted of large witness statements that were monotonous and often lost their way amidst the menacing landscape of the jungle. This stilted rhythm made The Vortex incredibly hard to read, and at times I felt completely lost. The reviewer in me admires Rivera for writing about such a sprawling wilderness full of evil, calling it The Vortex and making the prose just as confusing. However, the reader in me found it challenging to make sense of, and did not admire Rivera’s approach to how he constructed the narrative.

Ultimately, while the enjoyment of reading was at times a bit questionable, I liked this book and the story that Rivera was trying to tell about life in Colombia at the time. Rivera brings so much social context to the novel and it is such a core part of the story. A fictionalised tale sat among the political and social context of the time is a story I admire. I found a review of The Vortex in the New York Times from 1935 (!) that said ‘Rivera combines stark realism with lyrical romanticism’ and almost a hundred years on, that comment still stands.1 Rivera remarkably combines this almost western adventure tale full of cowboys and Indians with sharp and compassionate denunciation of the horrendous human rights abuses that took place in such a romanticised landscape.

The Vortex is an impressive novel and while it is not my favourite Colombian classic I have read (which is December Breeze), I enjoyed the opportunity it gave me to learn about a part of history I knew so little about. I would call it a borrow and recommend it to anyone who is interested in adventure stories and learning about the Amazonian rubber boom.

And that concludes my December Reads! My favourite book of the month was ‘A Spring of Love’.

My first book of January is ‘Independent People by Halldór Laxness’. I have been working my way through this for a couple of weeks now. I am having to exercise some patience that I am not reading this as quickly as I normally do, but I think I am enjoying it? While dense, and at times didactic, it is a generational story and they are a favourite of mine. Thus, I do believe it is worth it, even if I am reading it slowly.

Let me know your thoughts:

❀ What have you read and enjoyed in December?

❃ Have you read any of these books? What did you think?

❁ Do you have any book recommendations for me based on the themes of this month?

Thank you, as always, for reading. I hope you found a book you’d like to read!

I will be back in your inboxes in a week or two with my favourite reads of 2024 and some reading goals for 2025. I look forward to sharing them with you, and subsequently hearing about yours.

See you soon,

Happy Reading! Love Martha

If you know someone is always looking for intriguing and unique books to read, share this newsletter with them!

Catch up on what you might have missed:

And what I was reading in December 2023;

I frequently look back at this month and think what an amazing reading month it was! December Breeze, Land of Snow and Ashes, Small Worlds and Every Drop Is A Man’s Nightmare are all amazing - I’d recommend all of them to you.

Remember to subscribe if you enjoyed this and want to receive recommendations straight to your inbox!

I endeavour to always introduce you to books that don’t get coverage elsewhere. That is a promise.

This review is found on page 8 through this link; https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1935/04/28/95070024.html - I have to say, finding a century old book review was so much fun. The history graduate in me started pouring over old NYT book reviews and made me think of what a great motivation that is for reading classics/books that were published long long ago. To be able to compare how a novel was read and interpreted a century ago to now is a remarkable thing.

Oh I INHALED Ali Smith’s Gliff (sp?!) on holiday last week and I loved it to bits. Just ordered Autumn 💕

Finally catching up with all my newsletters! A Spring of Love sounds fantastic - added it straight to my list!

I also can't get on with Ali Smith for the life of me. She's all style no substance for me.