August Reads

Misogyny, revolution and perception + more Women in Translation recommendations

Welcome to ‘Martha’s Monthly’, August Reads edition! Several books this month explored misogyny, revolution and perception. Misogyny was discussed by books that interrogated the presence of femicide in society, as well as women being trapped by society within domestic roles. Revolution was encapsulated by novels exploring political and social upheaval; books that explored the demands of others for a change, whether structurally or behaviourally. Finally, perception was explored by how we choose to present ourselves to others, and how others view, or judge, us.

Because August was ‘Women in Translation Month’, every translated novel I read last month was written by a woman. To see these on Martha’s Map, including authors from Finland, Brazil, Spain, Poland and Turkey, click here.

For those who are new, buy, borrow, bust is my recommendation key: Buy = I immensely enjoyed and highly recommend this book. Borrow = I think this book is still well worth a read and I’m glad I read it. Bust = I wouldn’t recommend this book from my own reading experience.

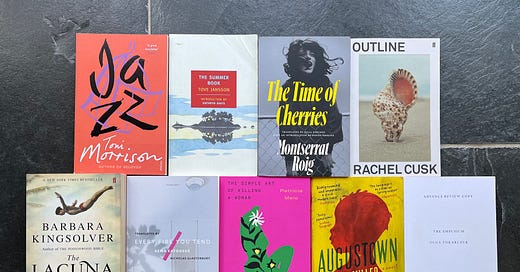

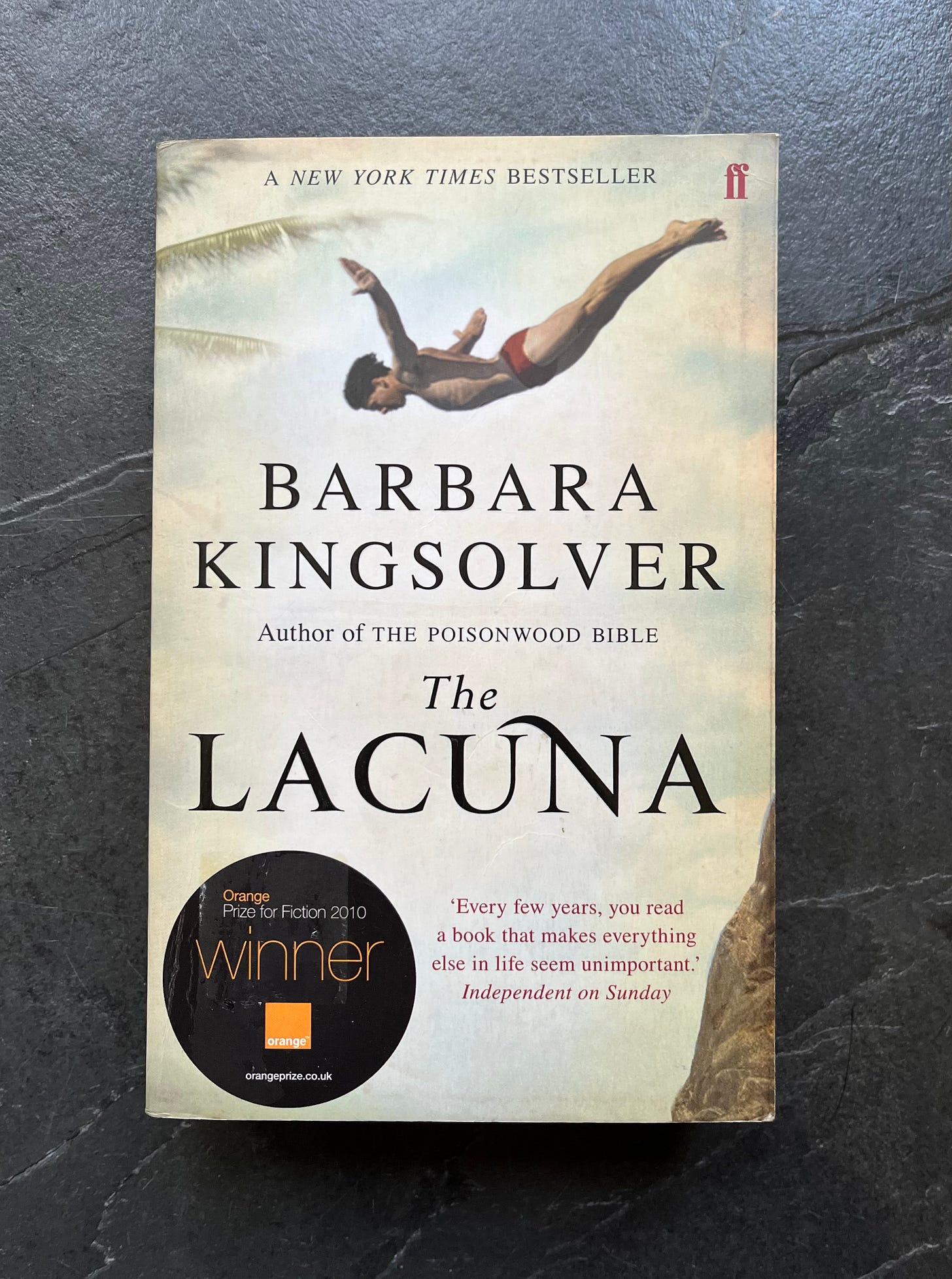

‘The Lacuna’ by Barbara Kingsolver. Born in America and raised in Mexico, Harrison Shepherd is an afterthought to his mother, Salome. This disinterest from his mother encourages Shepherd into a life of observation. In 1935, Shepherd is working in the household of famed muralist Diego Rivera and his wife Frida Kahlo. Sometimes a chef, sometimes a secretary, Shepherd is always an observer within the household. He records his experiences in diaries and notebooks. When Bolshevik leader Lev Trotsky is being harboured as a political exile in the Rivera household, Shepherd becomes inadvertently involved with art, communism and revolution. His aim for an invisible life is thwarted forever as he is thrust into a life touched by politics that exemplifies the breach, or the lacuna, between truth and public presumption. ‘The Lacuna’ is a poignant and deeply interesting novel about the intersection between arts, politics and culture.

‘The Lacuna’ begins with Shepherd’s own diary entries from when he initially moved to Mexico as a boy. This section is fundamental to understanding his character, as Kingsolver sets up ‘The Lacuna’ as a story of significance and mystery. This mystery is cemented by the archivists' note early on in the novel, which makes it clear this is a posthumous work. Generally, I think this format creates a palpable level of anticipation for the novel as the reader is driven by the desire to know why an archivist is publishing their work after their death, and more importantly how they died. How did this unassuming and insignificant boy become someone worthy of posthumous publishing? Shepherd recording his own experience in the Rivera house, as well as the archivist publishing his life’s recordings about said people in the Rivera house, begs the question; what does it mean to tell a story about someone else's life? Kingsolver has taken the real life events of Kahlo, Rivera and Trotsky and created a fictionalised character in Shepherd to transform them into a emotionally driven tale about the delicate relationship between private and public life. This form of creating a story that feels more real than real life is eloquently discussed by

in this piece linked here which she published while I was deep into the world of ‘The Lacuna’. It encouraged me to think more critically about the role of the form that Kingsolver had chosen to tell this story.Shepherd’s life span bears witness to the creation of nationhood of the American ideology, with fear mongering about immigrants and the threat of communism emerging across the country. Kingsolver uses Shepherd as a vehicle to explore the rising fear of ‘foreigners’ and the increasing encouragement from the state of the changing of American identity; the essential facet of Americanism is rooted in ‘othering’ people. ‘The Lacuna’ was written before the concept of fake news became as rampant as it has now, but eerily Kingsolver is interrogating how dangerous news cycles can be. She explores how an obsession with easily identifying people and categorising them into digestible boxes incites hatred and damages communities. Through historical figures such as Kahlo, Riviera and Trotsky, who were defiant to such categorisation and subscribed to radical belief systems, Kingsolver explores the relationship the ‘new world’ has to identity, politics and nationhood.

‘They have the audacity to say ‘That’s a finished product!’ But any country is still in the making, Always. That’s just history, people have to see that.’ - p.562 in ‘The Lacuna’

The Lacuna, spanning nearly seven-hundred pages, encompasses several stories within a single work. The joy of a book this big, at least for me, lies within the commitment you give it; to come back to the story everyday for a prolonged period of time, to become so familiar with the characters that you are filled with anticipation to know what happens next. I really enjoyed the length of ‘The Lacuna’. The book is not punchy, but instead layered with a lot of reading between the lines. The novel is made up of three stories; Shepherd’s childhood, Shepherd’s experience working for the Rivieras (my favourite) and his life after this experience (I am deliberately trying to be vague here). The first was my least favourite, as the story does take a while to get moving. Shepherd is a man who is about observation, introspection and deep thought. In an attempt to not give too much away about the plot, the novel ultimately suggests that politics, art and identity are intensely intertwined. As a forever admirer of Frida Kahlo, I deeply enjoyed the blend of fact and fiction about her art, fashion and relatinships. 1

In my opinion, to give you any more detail on the plot of ‘The Lacuna’ would be to ruin it. While the novel is very different to ‘Demon Copperhead’, there are some similarities. Kingsolver is an incredible writer, and to read her work is a gift because she creates worlds with such ease. I would recommend ‘The Lacuna’ and call it a buy. It was not a perfect novel by any means, but the journey of reading and learning about Shepherd’s life was very enjoyable. Kingsolver’s emotive writing is enthralling. Next summer, I think I will read ‘Prodigal Summer’.

‘The Summer Book’ by Tove Jansson is the snapshots of a grandmother and her six-year-old granddaughter, Sophia, spending their summer together on a tiny island in the Gulf of Finland. Together they amble over coastline and forest in easy companionship, build boats from bark, create miniature villages and write stories about bugs. Sophia is impetuous, as most six-year-olds are, and volatile, while her grandmother is wise and unsentimental. Gradually the two come to understand each other's fears, desires and yearnings as an understated but fierce love emerges between them. Together they share frank discussions about life, death and the existence of God. Jansson creates a whole world on this tiny island, imbued by the varied joy and sorrow of life, as well as the emotive experience of witnessing the natural world.

‘The Summer Book’ is told in a series of twenty-two vignettes. While an explicit plot is absent, the vignettes read as a collection of connected short stories. Each one stands on its own as an individual story, but together they draw a heartwarming picture of the human experience and our connection to the natural world. Jansson writes incredibly beautiful imagery of island life; the sea, beach and forests. I would go as far as to say that ‘The Summer Book’ has to be read in the summer (maybe this is an obvious statement?) I read this book under a canopy of trees in the blazing August heat, and all that I could think that would make it better would be if I was next to a body of water. The warmth and nature surrounding me added, for the better, to my experience of reading this. Jansson’s prose inherently idealises the atmosphere of summer;

‘A long blue landscape of vanishing waves that only left a small wedge of quiet water behind them.’ p.30 in ‘The Summer Book’

While the imagery was beautiful, what I found the most interesting within ‘The Summer Book’ was the direct and impatient characteristics shared by Sophia and her grandmother. Our protagonists being at contrasting, the precipice and closing, ends of life, create a relationship where there are almost no inhibitions. Both protagonists are impatient, mirroring each other in their attitudes towards life. They approach conversations about death in a very frank and direct way, they lack inhibitions, and rarely consider the impact of their behaviour or actions on the other. It perhaps sounds cruel, but instead it creates an interesting tone for the book that in many ways unintentionally criticises the restrictive behaviour that emerges in the ‘middle’ of life. Sophia and her grandmother have a loving relationship that is not ever put into question. Together they value and appreciate honesty, play and freedom, a dynamic that I don’t think would be as prevalent between any other age pairing. This tone of honesty and play runs through the book, painting a simple island existence. Both ages are untouched by societal expectation or fear, allowing them to enjoy time in a joyful and selfish way.

The vignettes tell the story of the island through them pottering around, tending to plants and using their imagination. There is little thrust within the novel and at times, the book felt lacking in grip. I think the focal point of ‘The Summer Book’ is a gentle and reflective ambience about island life, and more expansively, the role of nature in our life as a whole. How unchanging nature is over the years, and how our individual lives just pass through the everlasting seasonal change. Jansson’s writing was tender and quiet; enjoyable but not one for those who like a strong plot. I appreciated the atmosphere the novel created, reflecting on the relationship between the natural world and the human spirit. It was a gentle read, which is unusual for me, and I would call ‘The Summer Book’ a borrow.

‘The Simple Art Of Killing A Woman’ by Patrícia Melo is a story about femicide in Brazil and the power of women in the face of male violence. Our narrator is an unnamed young lawyer. To escape an abusive partner, she accepts an assignment in the Amazonian border town of Cruzeiro do Sul. There, she meets Carla, a local prosecutor, and Marcos, the son of an indigenous woman, and learns about the epidemic of violence against women that is out of control across Brazil. What she finds in the jungle is not only relentless oppression, but a longing for answers for an unsolved crime from her past. Through the ritual use of ayahuasca, she meets warrior women on a path of revenge and recovers the painful details of her mother’s murder. ‘The Simple Art of Killing A Woman’ is an angry and powerful story about life under the patriarchy.

The unnamed protagonist anchors the story, offering a unique perspective on femicide as both a prosecutor and the daughter of a murder victim, having lost her mother to her father’s violence. This intersecting relationship with femicide leads our narrator to have an understanding of violence against women and how it can manifest. Melo articulates that no amount of personal or professional understanding of femicide could prevent a woman’s proximity to it because it is so inherently ingrained into society. Our narrator comes to understand this when her partner becomes physically, and emotionally, abusive. Melo writes these parallel narratives surrounding our protagonist as she works on the cases of murdered women, tries to understand the murder of her own mother and navigate her abusive partner. These interconnecting storylines work incredibly well in painting a picture of femicide victims, perpetrators and prosecutors. Melo is attempting to interrogate the issue of femicide from all sides.

This novel is a war cry about femicide and the sheer number of women who are losing their lives at the hands of violent men. Melo eloquently articulates how society, the legal system and the police don’t seem to care enough to even investigate, let alone prosecute, these crimes. As of July this year, violence against women in Brazil, including stalking and raping, has reached a record high.2 The novel is brutal as it interrogates these societal attitudes towards women in Brazil. ‘The Simple Art of Killing A Woman’ questions how certain aspects of our patriarchal society breed hate, violence and the objectification of women in such a deeply acceptable way;

‘Of course they aren’t born like this. [...] the majority of them, [..] have to learn to hate before they can kill. [...] There is no shortage of teachers. Fathers teach it, the state teaches it, the legal system teaches it, the market teaches it, and culture, and propaganda [and] pornography’ - p.91 in ‘The Simple Act Of Killing A Woman’

Melo suggests how under the patriarchy, hating women is within the DNA of humanity; it is everywhere you look. The novel explores the ritualistic murder of all women; but especially indigenous women. Melo fiercely examines where gender and racial minority intersect to create a blind spot within the law; how this double oppression results in and immense and habitual miscarriage of justice;

‘Indigenous people are not invisible in our society the way Black people can be. [...] They simply don’t exist. They were decimated; they’re still being decimated. Take a look at the stats at the Ministry of Racial Equality: there isn’t a single policy for indigenous people. They simply don’t belong to our society - they don’t exist. This is why [redacted]’s death is all the more unacceptable. They killed a unicorn’ - p.161-162 in ‘The Simple Act Of Killing A Woman’

Melo explores the nuances of femicide and the tiers to getting the justice system to care. She interrogates how the law is just for ‘white and urban women’ and how indigenous women are being subjected to live with violence that is collateral damage from how indigenous people are treated across Brazil. 3 Melo devastatingly highlights the level of corruption that exists within the police and how impossible of a task it is to get them to care about any woman being murdered, especially an indigenous one. While emphasising the brutal treatment of indigenous women, Melo also offers an understanding about other aspects of the indigenous community in Brazil. She addresses their lack of political and social agency within the country and the language barriers that exist which isolate the women from communicating outside the community. The novel makes an attempt at exploring their historical and contemporary interactions with the law and what that looks like.

Alongside the brutality, the novel also contains lighter moments, particularly during our protagonist's ritualistic use of ayahuasca to remember her mother. Melo examines the relationship between ayahuasca and the indigenous community, their relationship with spirituality and the tradition. Our protagonist's experience with this psychoactive is one of positivity that is nurtured and exemplified by the women she is surrounded by, illustrating the power of women in the face of adversity.

‘The Simple Art Of Killing A Woman’ is a fantastic and unique thriller that I enjoyed reading; Melo’s voice is humorous, intelligent and scathing. I would recommend it and call it a buy! This book reads like a gut punch on women’s rights and all the progress that has not been made for women of colour. Despite the harrowing nature of the novel, I laughed several times while reading.

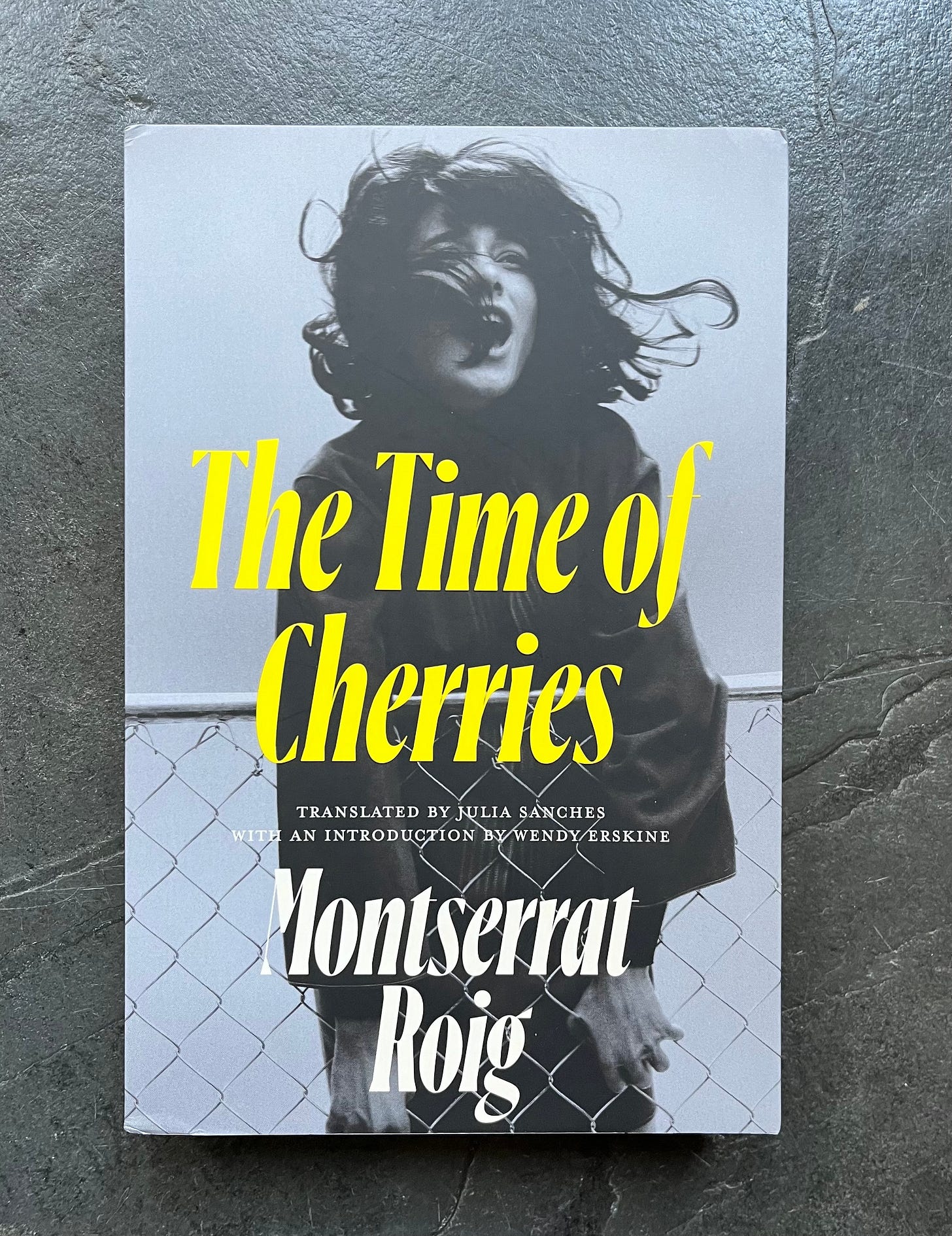

‘The Time of Cherries’ by Montserrat Roig. After twelve years abroad, Natàlia Miralpiex returns to Barcelona, and her family, in Spring 1974. Francisco Franco may still be in power, but his death is only two years away. Political, sexual, and artistic change is in the air. The younger generation write poetry, listen to American musicians and talk of a freer future. However, the older generation carry the hidden wounds of the Civil War, divided loyalties and their own thwarted dreams, rebellions and desires. ‘The Time of Cherries’ explores the complexities of social change and how this affects society at large, questioning how easily we adopt pain and oppression into our collective memory.

‘The Time of Cherries’ reminded me of ‘All Our Yesterdays’. They share similar sentiments of life under fascism in Europe. Instead of the reported speech found in Ginzburg’s writing, Roig writes her exploration of living amidst authoritarian rule with first hand speech and action. While Natàlia is our primary protagonist, the novel includes other points of view from her family members. Natàlia, her brother and his wife represent the later years under Franco’s dictatorship. Whereas, Natàlia’s father and aunt offer the perspectives of the civil war and the inauguration of Franco as ruthless leader. The family, as a collective, represent the change that has taken place in Spain across a single generation. ‘The Time of Cherries’ grants the reader a snapshot into a family where life has changed dramatically, and how the political climate has directly affected their perception of the world and belief systems.

Throughout the novel, Riog seamlessly interrogates how the personal is political. ‘The Time of Cherries’ articulates how the fallout of war and oppression can be mundane. Communicating how political and social turmoil most fiercely affects the personal lives of those who were subjected to experience it, rather than those who enacted it. The novel explores how politics affect spheres that you initially wouldn’t consider; such as relationships. Roig’s writing is both expansive and intimate as she traverses the eroded trust and loyalty between family. Most interestingly, Roig explores this in relation to how politics can enter the home, affecting the way people engage with each other emotionally and physically. I thought the way Roig interrogated how religion also had a profound impact on sexuality was absorbing. These are concepts which are often discussed in theory, but rarely do you get a glimpse to try and understand what this means for people's personal life; Roig illuminated this with searing honesty and ease.

Roig gives voices to those who would have been largely ignored at the time; women and the elderly. She presents how the women are struggling with identity, both feeling trapped by domesticity and trying to strike out against it. The exploration of gender under a dictatorship was sincere and incredibly interesting. While the novel was not forthcoming in facts about Franco’s dictatorship, it is instead driven by palpable emotion. Which, ultimately, paints a much richer and honest picture of life at the time.

‘The Time of Cherries’ does not have a straight forward plot, instead it is a meandering and rich stream of consciousness told in a nonlinear way by multiple protagonists; but it works so well. Similarly to the comments I made about the value of learning from fiction in relation to ‘Enter Ghost’, these also apply to ‘The Time of Cherries’. Roig gives exceptional and emotive insight into life under the dictatorship, creating a landscape of rich understanding of the politicisation of daily life within the home. Roig uses the familiar constructs of the family, relationships and domestic spaces to play with communicating the wider political atmosphere at the time. She flawlessly humanises those living under authoritarian rule, creating an avenue for the reader to understand the emotional and psychological impact of fascism on society. To understand how political decisions affect one's relationship with themselves and society as a whole.

I thought this book was excellent. I was infatuated with Natàlia’s family and understanding how the dictatorship affected their lives in variable ways. Roig is a phenomenal writer, creating such a vivid sense of place and time on the page. I loved the exploration of female identity and sexuality within the wider picture of the dictatorship. I would really recommend this and call it a buy! This was perhaps one of the best historical fictions I have read in a while, which is saying something because it is my most dominant reading genre.

‘Jazz’ by Toni Morrison was my classic novel of the month. In the winter of 1926, Joe Trace, a middle-aged door-to-door salesman of beauty products, shoots his teenage lover to death. His lover of three months was eighteen-year-old Dorcas. At the funeral, Joe’s wife, Violet, who frequently stumbles into dark mental health episodes, tries with a knife to disfigure Dorcas’ corpse. ‘Jazz’ is a story of love and obsession, bringing us back and forth in time with a narrative assembled from the emotions, hopes, fears and realities of black urban life.

‘Jazz’ is the sequel to ‘Beloved’, which I loved, so naturally I had high expectations for this novel. Perhaps this was my downfall, but I did not like ‘Jazz’. What I thought the novel did do well was the exploration of the emerging urban experience of African Americans in the early twentieth century. Morrison interrogates the ‘Harlem Renaissance’ and the blossoming of the movement which embraced self-expression and rejected the long-standing degrading stereotypes the Black community had suffered for centuries in America. 4 In the foreword, Morrison discusses how writing ‘Beloved’ evolved into the topics she explores in ‘Jazz’;

‘Beloved unleashed a host of ideas about how and what one cherishes under the duress and emotional disfigurement that a slave society imposes. One such idea - love as a perpetual mourning (haunting) - led me to consider a parallel one; how such relationships were altered, later, in (or by) a certain level of liberty.’ - Toni Morrison in ‘Foreword’ in ‘Jazz’

The exploration of new urban liberty's impact on Joe, Violet, and the broader African American community was poignantly conveyed. Morrison effectively portrays the shift from rural to urban life, highlighting the change in opportunities and the effects on individuals and the community. Both ‘Jazz’ and ‘Beloved’ explore the severe change from enslavement to freedom in just one generation and the enormously destabilising and alienating impact that this had. It is a change so transformative and traumatising that trying to acknowledge it within this review feels challenging. Within each Morrison novel I have read, she continues to exceptionally address and discuss the emotional and psychological impact of life after being enslaved on Black families and communities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Centrally, I felt that the story was about exploring choice, and the unfounded freedom that exists within finally having the ability to have autonomy. This theme is explored empathetically and honestly in ‘Jazz’, and for all the faults I thought the novel had, this is not one of them.

However, I thought the narrative structure was weak in ‘Jazz’. The murder of Dorcas, and the subsequent violent attack on her body, is a springboard for discussing the past and trying to understand why Joe and Violet behaved in the way they did. In a meandering narrative, Morrison is attempting to help the reader understand how these violent acts from Joe and Violet come from somewhere; they are lashing out after centuries of oppression as Morrison depicts how relationships were altered by a certain level of liberty. As a concept this works, but what didn’t work was the way the story was told. The narrator is nebulous, and we are never quite sure who they are. While this allowed there to be several perspectives and narrators, I felt it also meant the thread of the story was often lost and sometimes completely absent. The frequency of flashbacks and differing perspectives was often disorientating. I understand why Morrison opened with the violent acts of Joe and Violet, but starting with the most gripping event, with the rest of the novel petering out felt inconclusive and tiresome. By the end of the novel, I was bored of Joe and Violet and the indirect narrative of perspectives.

Morrisons prose is always arresting and beautiful, but the structure of this novel just did not work for me. I deeply enjoyed some of the more historical storylines, such as true Belle and Golden Gray, which explored Joe’s ancestors and his family tree. Those flashbacks were vibrant, illuminating the drastic contrast in liberty and lifestyle between two generations of the Trace family; they reminded me of Beloved. ‘Jazz’ had such a strong concept and opening few chapters, but as the story continued, the pulse of the novel died out. I would call ‘Jazz’ a bust as I wouldn’t recommend it. By definition, ‘buy, borrow, bust’ is just a recommendation key, not a rating system. I deliberated on how to categorise ‘Jazz’ for a long time, but ultimately this is based on my own experience. I am incredibly interested to hear from anyone who loved this novel and thought the nebulous narration style was perfect? For my next Morrison, I am considering ‘The Bluest Eye’ or ‘Song of Solomon’.

‘Outline’ by Rachel Cusk is a novel in ten conversations. It follows our protagonist, a novelist teaching a course in creative writing over an oppressively hot summer in Athens. She makes a friend on the plane, meets other writers for dinner, goes swimming in the Ionian Sea and teaches students. The people she encounters speak volubly about themselves; their fantasies, regrets and longings. Through these revelations, a portrait of our narrator is drawn out of her interactions with others. Outline’s introspection offers a provocative exploration of identity, self-expression and the human experience.

‘Outline’ is a book about perception and exploring what it means to be alive. It interrogates our relationships and how we tell stories to ourselves, and others. I was infatuated by how Cusk writes with both immediacy and depth about a variety of human life. ‘Outline’ is a novel of conversations where there is little plot. The narration consists of a succession of, sometimes quite intense, monologues from a group of very thoughtful and intelligent people. They are all reflecting on their careers, relationships and families and how it has shaped who they are today. They query out loud with our narrator about what certain milestones, or the absence of them, mean about the trajectory of their lives. As someone who is deeply social and analytical, I really enjoyed this narration style. It was so interesting to be given these intense and detailed snapshots of other people's lives and question why they are telling our protagonist what they are telling her; how do they want to be perceived by her? What are they communicating, or not, with these stories?

Our protagonist operates as a vessel for us to find out about those she spends time with. Her mental clarity is penetrating as she inspires revealing and significant confessions from those she spends time with. I enjoyed the facelessness of her and not knowing anything about her - we do not even learn her name until over two-hundred pages in. ‘Outline’ reminded me of ‘The Details’, which asked ‘who is the real subject of a portrait, the person being painted or the one holding the brush?’. This sentiment applies to our novelist as we learn about who she might be through her interactions with others. Cusk is an incredibly skilled and talented writer to be able to paint a picture of our protagonist without ever directly describing her. Reading ‘Outline’ felt like piecing together a puzzle, in the best way. Cusk intentionally writes a protagonist deliberately vague in order to tell the stories of those who surround her.

The conversations I enjoyed the most were those focused on one person's life, where they discussed in depth their hopes, dreams and losses. Most of these conversations are with people who are middle aged. Meaning, the conversations traverse the complexities of having lived for many years, particularly topics such as parenthood, divorce and feeling dissatisfied with the trajectory of one’s existence . Cusk’s writing asks how we attempt to make sense of it and give all experiences meaning.

Nearly every conversation provocatively examined the essence of life: What defines success? How do we judge others based on what they reveal? How do we shape others' perceptions by sharing or withholding information? Needless to say, I was enthralled.

I loved ‘Outline’. The writing was masterful as it played with the concept of an unreliable narrator. By freeing the narrator of a physical body, the reader is allowed to paint a much more emotionally complex portrait of her. Our protagonist is not defined by how she looks, but instead how she feels. To be able to ascertain information about our protagonist through how she interacted and responded to others was deeply engaging. I would absolutely recommend it and call it a buy. I look forward to reading the next book in the trilogy, ‘Transit’, soon.

‘The Empusium: A Health Resort Horror Story’ by Olga Tokarczuk. In September 1913, Mieczysław Wojnicz, a student suffering from tuberculosis, arrives at Wilhem Opitz’s Guesthouse for Gentlemen; a health resort in what is now, western Poland. As part of their treatment, everyday the residents gather in the dining room to consume the hallucinogenic local liqueur. Imbued with this drink, they obsess over money and status, debating aspects of patriarchal society; Will there be war? Monarchy or democracy? Do devils exist? Are women inherently inferior? Meanwhile, disturbing things are happening. As stories of shocking events in the surrounding highlands reach the men, a sense of dread builds. Someone - or something - seems to be watching them and infiltrating their world. As he attempts to unravel truths within himself and the mystery of the forces beyond, Wojnicz does not realise they have already chosen their next target. Tokarczuk’s storytelling is a blended parable of feminism, horror and comedy.

Tokarczuk is an esteemed writer and the release of her new book is very exciting. I feel lucky to have been able to read it before publication, and I am feeling the pressure of being able to communicate to you the nuance, intelligence and politics found in ‘The Empusium’.

Written like a late eighteenth century classic, ‘The Empusim’ is ominous and twisted, dripping in atmosphere. Tokarczuk leads the reader into a profound state of confusion as we struggle to work out what is going on. The horror is subtle, creating a foreboding sense of dread. We follow this group of sick men into the mountains to get better in a Gentleman’s Club by taking psychedelics. Tokarczuk’s style is always more than meets the eye, so I knew that this plot would develop into something much more nuanced.

There are almost no women in this story, yet the men are obsessed with them. They discuss their role in society constantly;

‘Wojnicz had noticed that every discussion, whether about democracy, the fifth dimension, the role of religion, socialism, Europe, or modern art, eventually led to women’ p.129 in ‘The Empusium’

Wojnicz, our protagonist, is clearly different from the other men; often described, rather cruelly, as sensitive and strange. His perception of the dominance of the topic of women is not one shared by others. The discussions between the men about gender read like they were lifted from texts from the eighteenth/nineteenth century. The pages drip with misogyny, as the men discuss how women’s bodies are seductive, worthless and belong to society.

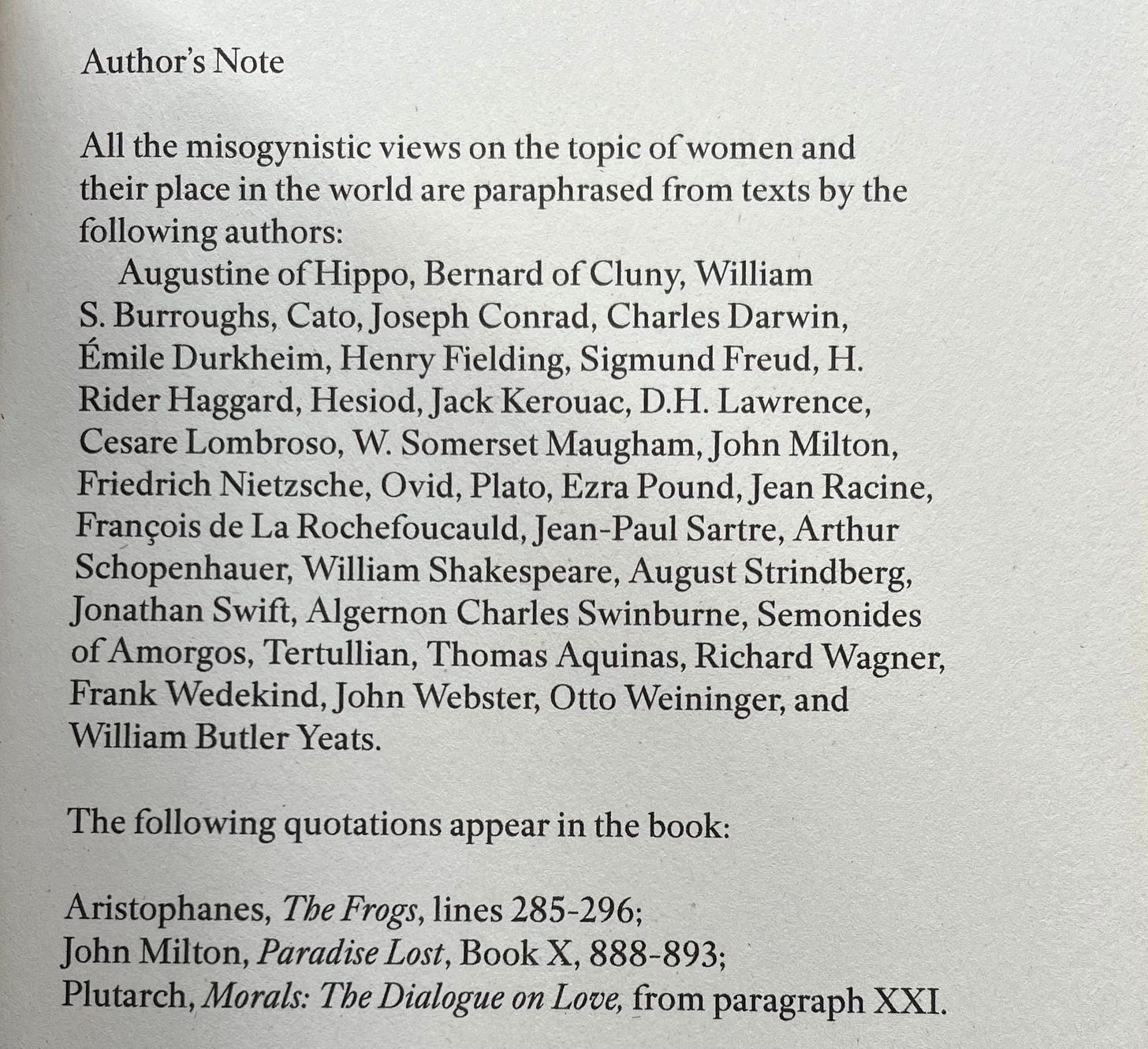

This feels like the perfect time to share the Author’s Note:

Tokarczuk has paraphrased the real misogynistic language from some of the most respected authors from the literary canon. The use of paraphrasing from these texts is genius on a multitude of levels, mostly because it demonstrates how terrified men were of women (historically and not so historically), which leads them to try and control them. The narration of ‘The Empusium’ is vague; distinctly addressing the reader as a collective ‘we’. The narrators appear to be a throng of female ghosts that haunt the forest nearby, the souls of women who were murdered in the witch trials in Görbersdorf in the seventeenth century.5 Unbeknownst to the men, the ghosts of these women pervade and dominate the landscape. There are many more revelations within this novel which I would love to discuss but I don’t want to spoil it - so that is all the plot details you’re getting!

Structurally, the thrust of this book ebbs and flows as you are desperately trying to figure out what is going to happen. I didn’t feel captivated for the entirety of the novel, but this changed at the end when it all came together. Tokarczuk has written a incredibly clever book, one that is a lot more than just a ‘story’. ‘The Empusium’ is full of history, and intellectually her creative conception of the novel is perhaps more impressive than the novel itself. It was not ‘easy’ to read - it is full of layers and nuance. It is deeply political, as all of Tokarczuk’s writing is, and I was incredibly impressed with everything this novel was trying to achieve.

‘The Empusium’ is all about perception. How we perceive others and how others perceive us. It was a shocking, weird and funny read. I would not start here if you have not read any Tokarczuk before, but if you have, I think you may really enjoy it. Not for the first time this month I have struggled with how to categorise the book in the recommendation format I use. Ultimately, I think I would call this a borrow because it was not consistently gripping and at times, felt slightly monotonous waiting for the mystery to be revealed. Nevertheless, the atmosphere created by Tokarczuk’s writing is incredibly impressive and I recommend the novel on the basis of how it reveals itself and makes you think long after you put it down. I would also recommend that you do not, under any circumstance, google what ‘empusium’ means before you read; save it for after.

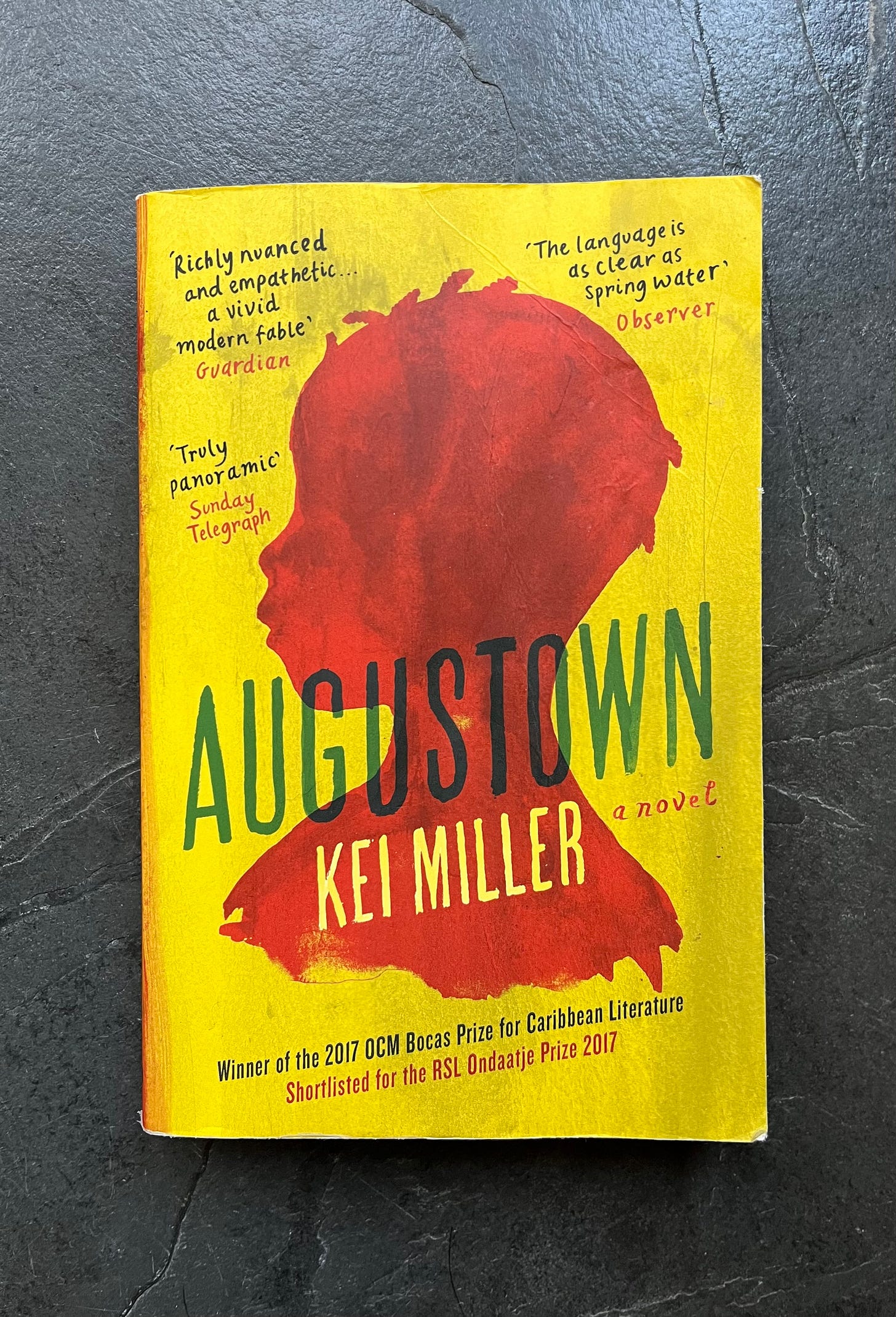

‘Augustown’ by Kei Miller is a story of impending disaster. One April day in Augustown, Jamaica, Ma Taffy sits in her usual spot on the veranda. Old and blind, she is a detailed observer; she knows everything that goes on in this small community. Which is why, when her six-year-old great nephew, Kaia, returns home from school with his dreadlocks shorn, she knows that trouble won’t be far away. While they wait for his mama to come home from work, Ma Taffy tells him the story of Alexander Bedward, the flying preacherman. A poor suburban sprawl in the Jamaican heartland, Augustown is a place where many things that should happen don’t, and plenty of things that shouldn’t happen do. Once more, trouble is brewing among the lanes of Augustown.

‘Augustown’ is a masterfully written exploration of history and legacy. The story unfolds gradually, as Miller reveals connections between characters and the town in a fluid, poetic manner. The novel’s exceptional pacing weaves together multiple lives, all building towards a powerful climax. The novel’s various points of view create a rich tapestry of life around Kaia and Augustown. Miller's prose is vivid and deeply moving, capturing the complexities of race, class, and segregation. I was moved by Miller’s characterisation and portrayal of the prejudice faced by the Black community.

’s piece on Toni Morrison’s paths of critical inquiry encouraged me to try and interrogate ‘Augustown’ and the function of race in the novel more deeply. The story of ‘Augustown’ uses a narrative, set against a background of institutional violence, to meditate on humanity and suffering. The novel creates an opportunity for the reader to try and challenge what is real and what is fiction?‘You may as well stop to consider a more urgent question; not whether you believe in this story or not, but whether this story is about the kinds of people you have never taken the time to believe in’ p.115 in ‘Augustown’

Augustown explores the relationship between the Black community and the police. While the novel is about ‘Blackness’, it is also about the religious prejudice of the Rastafarian faith, and the relationship they have to structures of power. Rasta dreadlocks symbolise a visible marker of faith, but also to a way of life that is opposed to the colonial/institutional legacy that remains in Jamaica. The function of this story is to meditate on what it means to be human, and the suffering that we enact on others due to fear of difference. Kaia’s hair is cut by a man who deems it untidy, an attitude rooted in the legacy of colonialism. What happen’s to Kaia is insidious; to shave the hair of a child, because you believe he is lesser than you as a result of prejudice, represents a universal cruelty of humanity that is confronting.6 While there are a variation of character perspectives in the novel, centrally they all focus on the role of systemic racism in society and how it creates or withholds opportunities. ‘Augustown’ operates as a mediation on humanity, the structural racism that exist within our world, and the violence and suffering it creates.

Miller's storytelling ability was remarkable and ‘Augustown’ is a novel that is so easy to read and enjoy. The story is captivating, exploring the complexities of Jamaican culture, history and identity. Miller eloquently explores social justice and the struggles of those who do not have a ‘fair’ life because of the colour of their skin. I loved this novel and I would absolutely recommend this and call it a buy.

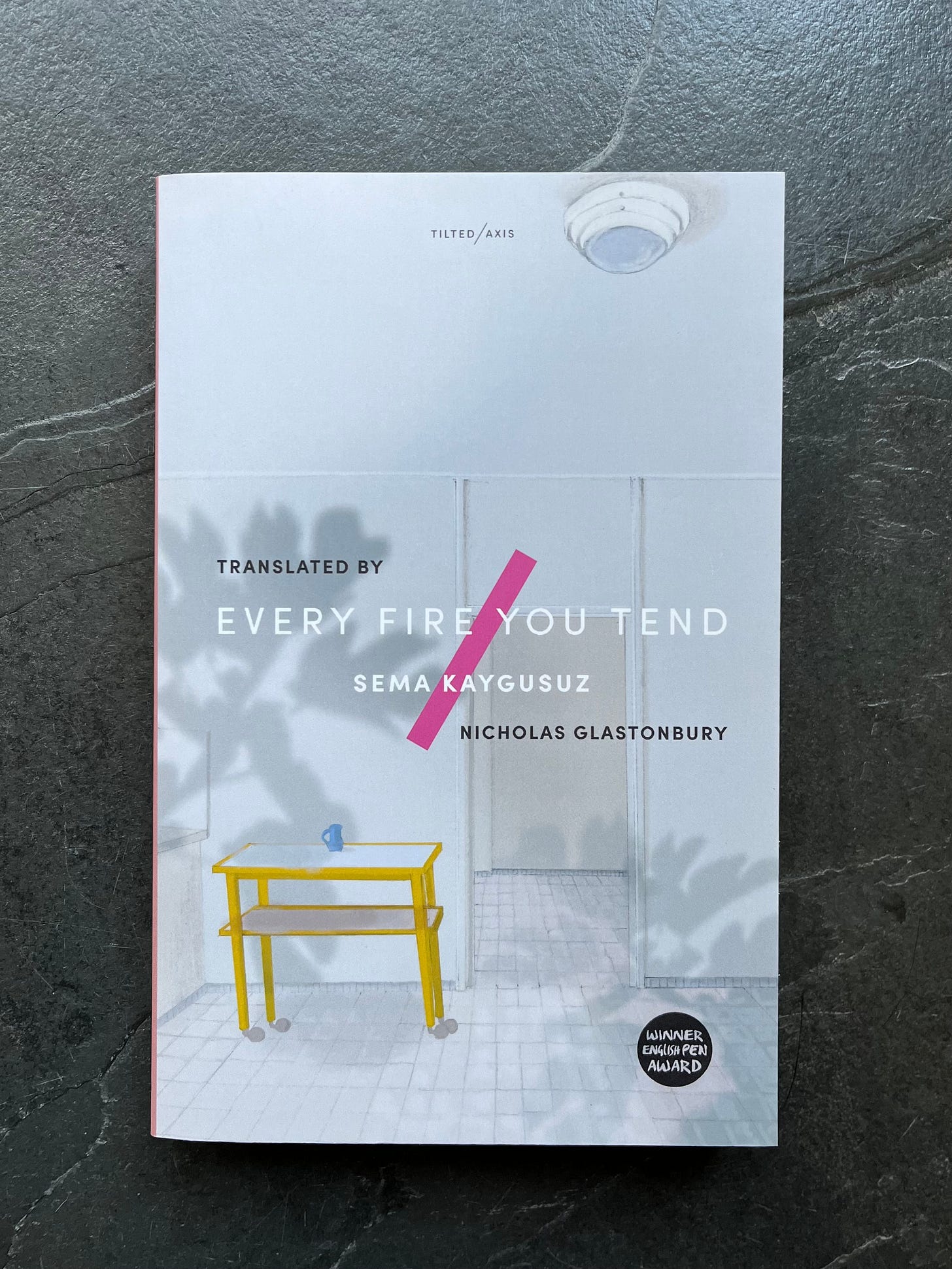

‘Every Fire You Tend’ by Sema Kaygusuz. In 1938, in the remote Dersim region of Eastern Anatolia, the Turkish Republic launched an operation to erase an entire community of Zaza-speaking Alevi Kurds. Inspired by these events, this lyrical novel grapples with the various inheritances of genocide, as they reverberate across time and place from within the unnamed protagonists home in contemporary Istanbul. Kaygusuz explores a still-taboo subject in a narrative fuelled by mysticism, wisdom and legend.

‘Every Fire You Tend’ is an incredibly lyrical story, structured around the legends and mythological stories of the Alevi Kurds. Kaygusuz’s writing is so lyrical that it was often very lost on me. Chapter to chapter, the writing is compelling and beautiful as it explores the stories that are central to the Alevi Kurds community and spirit. But together, the narrative felt incredibly fragmented and hard to follow. Perhaps this is down to the unnamed protagonist, who was unidentifiable in every way.7 ‘Every Fire You Tend’ read like a collection of short stories that were barely connected; equally atmospheric and disorientating. I deeply appreciated what the author was doing here; to humanise those who where so dehumanised by the genocide, to bring them to life after they were massacred. Kaygusuz is aiming to not reduce them to the violent and horrifying statistics that have plagued the community. I think she did this well, because all I have to take away from my experience of reading this novel is a, albeit vague, understanding of the mythology and legends that are so central to the Alevi Kurd community.

Perhaps I was looking for a different novel, because I wanted to learn about the genocide in a way that this novel was not willing to offer. I can understandably see the irony here; of wanting to learn about the genocide of a minority and being dissatisfied by learning about the community whom the genocide was committed against. I wanted to learn why the Dersim genocide is so taboo, how the massacre took place and the Turkish state banning Kurdish and restricting their culture. In looking for more of an educational fiction, I was automatically disappointed by the narrative style and format of this book. Isolated, the prose was incredibly imaginative and there were moments where I was really taken by the mythology. However, the history and international relations degrees in me desired facts and information, and this was not the route Kaygusuz wanted to take. I respect the way she approached this novel, sharing the legends and mythology that uphold the Zaza-speaking Alevi Kurds.

Ultimately, I wouldn’t recommend this book because I found it incredibly hard to follow and very fleeting in resemblance to a cohesive plot. While this may be a favourable structure for some, I sometimes struggle with nebulous and vague narration styles (clearly). I would call ‘Every Fire You Tend’ a bust. While I do categorise some books as a bust because I truly hated them (like Kairos…) I did not hate this, I just couldn’t gel with it or understand the story. To continue my goal to learn more, I think I will pick up ‘Kurdish Women’s Stories’ by Houzan Mahmoud soon, which sounds excellent and includes stories across the diaspora.

And that concludes my August Reads! My favourite read of the month was ‘The Time of Cherries’ and ‘The Lacuna’.

My first read of September is ‘The Bee Sting’ by Paul Murray. I started the summer by reading a rich generational story (East of Eden), so why not see out the summer on one too! I am about half way through and I am really enjoying the story so far.

If anyone has already read this, please let me know what you thought!

Let me know your thoughts:

❀ What have you read and enjoyed in August? Did you read any Women in Translation?

❃ Have you read any of these books? What did you think?

❁ Do you have any recommendations for me based off the themes from this month?

⚝ Have you ever read and disliked a classic novel, like I did with ‘Jazz’, and felt in the minority about your opinion?

Thank you, as always, for reading. Let me know if you found a book you’d like to read.

Recently, the readership of this newsletter has grown to over 1,300 of you (!) Thank you, from the bottom of my heart, for all the enthusiasm and love - the feeling is mutual <3

See you next month,

Happy Reading! Love Martha

If you know someone is always looking for interesting books to read, share this newsletter with them!

It will make you look cool and well read. (This is proven)

Catch up on what you might have missed:

If you weren’t around last year and are interested in what I was reading in August 2023, click here.

Before you go - if you enjoyed this, why not subscribe? <3

If you have wanted the opportunity to support this letter financially, I have recently turned on the ability to pledge a paid subscription. If you would like to show your support for the running of this newsletter, you are welcome to do so here.

For example, I have always liked this [https://nmwa.org/art/collection/self-portrait-dedicated-leon-trotsky/] self-portrait from Kahlo, she dedicated to Russian revolutionary Trotsky. To read a, albeit, fictional story about their possible relationship was a whole lot of fun.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jul/18/violence-against-women-in-brazil-reaches-highest-levels-on-record - a depressing but good read on this

This statement is taken from p.161 from ‘The Simple Act Of Killing A Woman’ by Patrícia Melo

If you are curious about the Harlem Renaissance, this is a pretty good brief history: https://www.history.com/topics/roaring-twenties/harlem-renaissance

This is what the story tell us. While Görbersdorf witch trials are not something I can find any concrete information on, witch trials in the 17th century were incredibly common in Eastern Europe at the time, with supposedly the last official one in Poland in 1783 - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doruch%C3%B3w_witch_trial

This story: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/13/us/supreme-court-prison-rastafarian.html & This story: https://www.voice-online.co.uk/news/2021/08/04/anger-as-rasta-teen-says-jamaican-police-cut-off-her-dreadlocks/ about the persistent use of shaving off dreadlocks as a punishment by the police force even today.

I cannot believe how many nebulous and vague narrators I have read this month. I need a break.

You make me wish I could get through books faster! My two year old has learned to say "mommy, no book. play" very well.

Martha I eagerly anticipate these every month! I am always in awe of how much care you put into your reviews and recommendations.