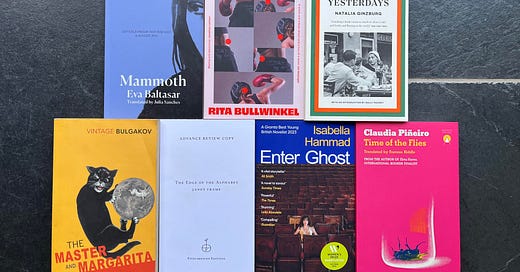

July Reads

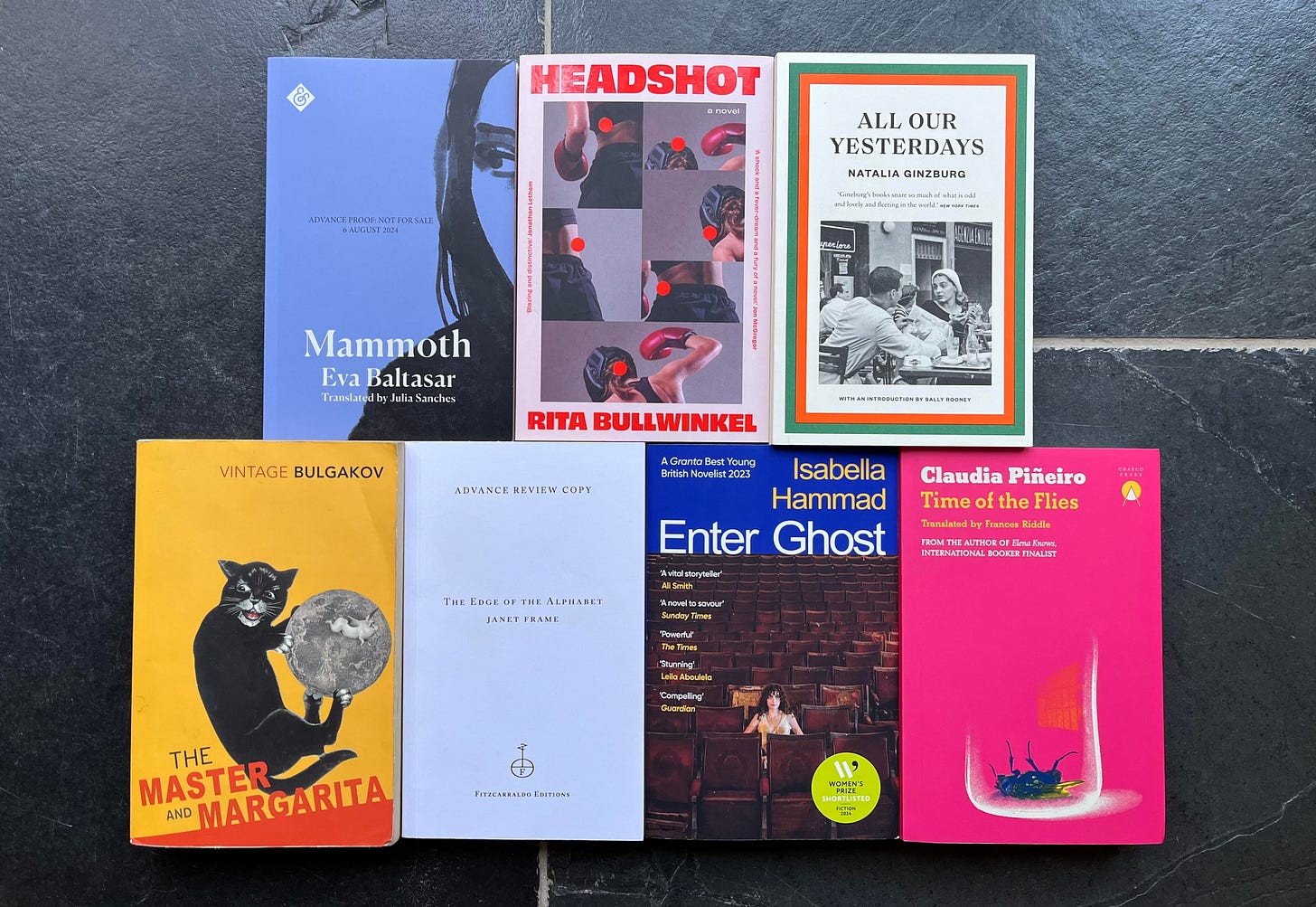

Unconventional motherhood & 'The Other' + Women in Translation Month and The Booker Prize longlist

Welcome to Martha’s Monthly, July Reads edition! When I was reflecting back on my reading in July, the theme that stood out to me the most was unconventionality. This manifested in two distinct ways; within motherhood and ‘the other’.

The concept of unconventional motherhood was explored through individuals who experienced strained relationships with their children, exhibit profound detachment from the role of motherhood, and possess an intense preoccupation with the idea of being pregnant. The notion of ‘The Other’ refers to individuals perceived as fundamentally different by the mainstream. This theme was explored through characters who exist on the periphery of society, leading lives that deviate from societal norms. In literature, ‘The Other’ often serves as a lens to critique social constructs and highlight the complexities of identity and belonging.

To see the translated reads from July on Martha’s Map, including authors from Italy, Argentina, Russia and Spain, click here.

For those who are new, buy, borrow, bust is my recommendation key: Buy = I immensely enjoyed and highly recommend this book. Borrow = I think this book is still well worth a read and I’m glad I read it. Bust = I wouldn’t recommend this book from my own reading experience.

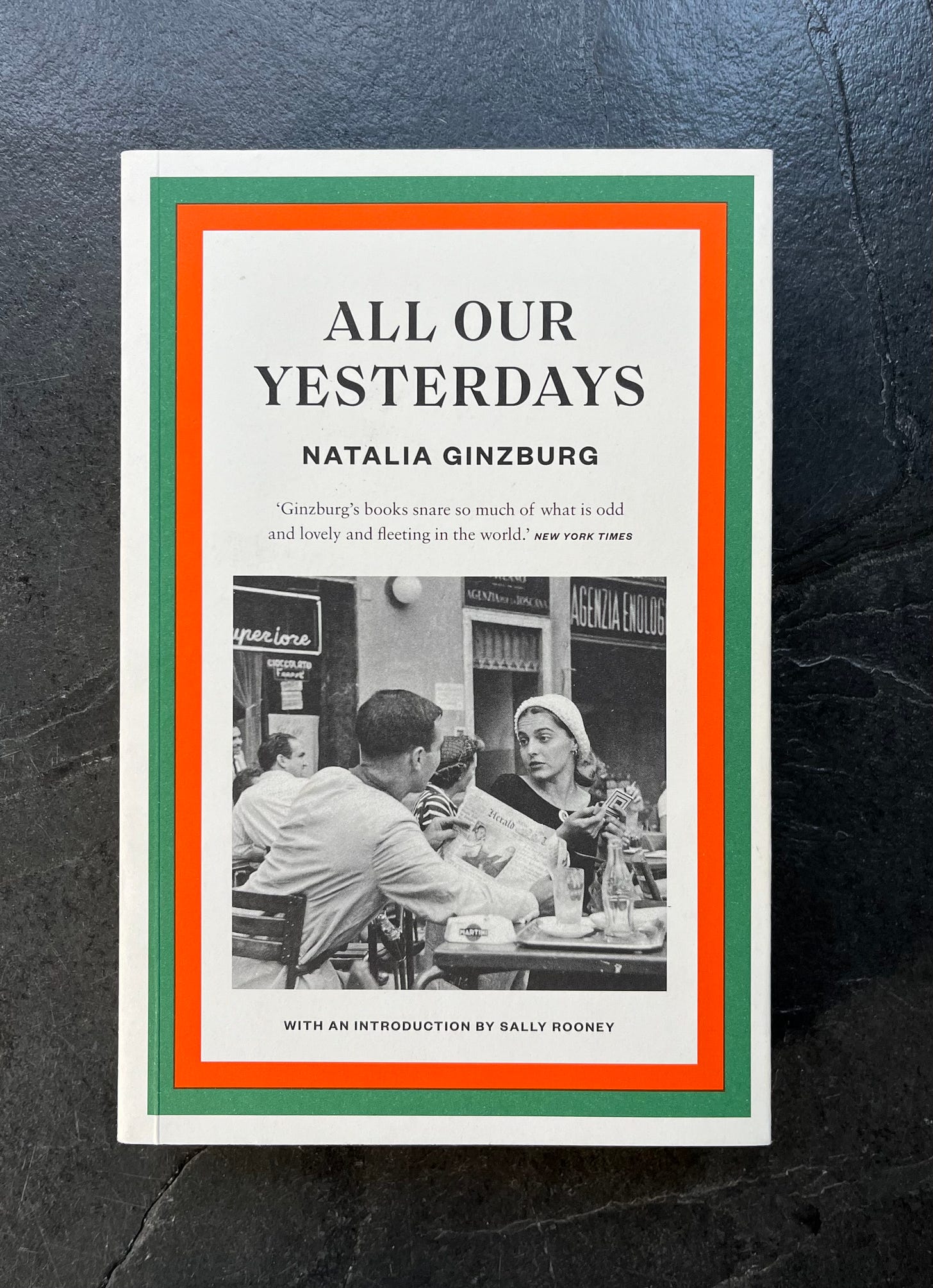

‘All Our Yesterdays’ by Natalia Ginzburg begins in a small town in northern Italy, in the years before the war, with a family: an ageing widower, his four children and the family’s companion, Signora Maria. Across the street in the ‘house opposite’, lives the owner of the town's soap factory, with his wife, his children and someone named Franz. Gradually, a protagonist begins to emerge named Anna. The novel goes on to follow Anna’s relationships with her family, the inhabitants of the house opposite and an older family friend named Cenzo Rena. Anna’s status as the protagonist remains a partial one, as we are sometimes taken away to explore the dreams, disappointments and desires of other characters. Among this political unravelling of Italy, Anna realises she is pregnant. To save her reputation she marries Cenzo Rena and they move to his village in the south. Their relationship is touched by tragedy and grace as the events of their life in the countryside run parallel to the war and the encroaching threat of fascism. At the heart of this deeply observational novel, Ginzburg writes a story that weaves together the complexities of family and resilience in the face of war and social upheaval.

Ginzburg (1916-1991) is known for recounting history; Italy’s war and post-war struggles through the perspectives of marginalised characters and individual family histories.1 While lesser well known than Italian author Elena Ferrante, Ginzburg’s work is arguably much more influential. Ginzburg led the most fascinating life, and while I want to prioritise using this review to reflect on the novel, I would encourage anyone who is interested to read about her life, career and family. 2

‘All Our Yesterdays’ is a quiet book that explores politics and society through the prism of ordinary life. Full of long sentences and intricate descriptions of life and relationships between one and other. It is a novel about family, about small everyday occurrences in life. The plot plods on, with no dialogue, only reported speech. This detachment from the dialogue creates a very undramatic story. Even in scandal, or the outbreak of war, it remains undramatic. Ginzburg’s steady writing reflects the flow of life, that emphasises how the everyday can remain mundane for some despite the occurrence of world altering events, like warfare. Anna and her siblings are trying to understand the world of politics and society among the inevitable evolution of life. Trying to make sense of where they fit in and how they take part in the wider political sphere.

I picked up ‘All Our Yesterdays’ because of the Sally Rooney introduction on the front. Anything Rooney loves, I am interested in. Since finishing, it is no surprise to me why Rooney loves Ginzburg, their writing reads similarly. Both women are deeply political within their writing, but not directly so. They both examine relationships between people in a specifically detached way. They seek to create beauty out of the mundanity of existence, exploring themes of fragility, love and the human experience. Ginzburg creates an impressive flow of writing, barely using quotation marks and relying heavily on the comma. There is this level of awareness they’re trying to give the reader, through their characters they are painting this political, social and economic landscape of the time. It’s equally introspective as it is outward looking. While Ginzburg is a talented author in her own right, who came long before Rooney, I think the contemporary comparison will help readers understand Ginzburg’s style and approach to storytelling.

I enjoyed reading ‘All Our Yesterdays’ but it does wane in captivating you. It is not a novel you can race through, and instead one that benefits from a slow read. I am not a slow reader, so this frustrated me at times. I wanted to fly through it much faster than the writing allowed. It is a very interesting historical fiction about Italy in WW2 which, if you know, is pretty bleak. For those who are fans of Shakespeare, you will have noticed that the title ‘All Our Yesterdays’ is lifted from Macbeth Act 5, Scene 5 - the soliloquy that sets the scene for Macbeth’s death. While ‘All Our Yesterdays’ is far from as outwardly dramatic as Macbeth, the sentiment of tragedy runs throughout the novel. Ginzburg explores the parallels of human nature, from the mundane to the horrifying, the story examines the nuances of humanity. The book explores this catastrophic unravelling of ordinary life in the wake of political and social upheaval.

Ginzburg’s writing is simple as the story is weaved through these long, descriptive sentences. It is very introspective and poignant about the human experience; what it means to be alive. Many may find this boring, but I enjoyed it. I am enthralled in Ginzburg as a writer and looking to read more from her. I would call ‘All Our Yesterdays’ a borrow. I want to read ‘The Dry Heart’ and ‘Valentino’. These new, very pretty, reprints of her novels can be found here.

‘Time of the Flies’ by Claudia Piñeiro. Fifteen years after killing her husband’s lover, Inés is released from prison. Her friend Manca has been released too, and together they’ve started a pest control and private investigation business. The service is by women, for women. But one of Inés' clients wants her to do more than kill bugs; she wants her expertise, and her criminal past, to help get her revenge on someone. The client, Señora Bonar, offers Inés a significant amount of money for her expertise. Inés understands this opportunity to be a straightforward job, until her estranged daughter shows up. Inés and Manca discover that things are not as they seem as they undertake an investigation into Señora Bonar and who she wants to revenge.

In true Piñeiro fashion, ‘Time of the Flies’ is a poignant thriller that explores the complexity of motherhood. Despite this being a theme in all three of her novels I have read, ‘Time of the Flies’ takes a explicitly feminist approach, exploring and discussing the role of women and mothers in society. Piñeiro was much more experimental in her approach to discussing how society perceives and defines mothers, as opposed to some of her other books (Elena Knows (2021) and A Little Luck (2023). An additional narrative runs parallel to the story, a stream of conversation examining the politicisation of womanhood and motherhood; where they intersect and divulge. It discussed all the complexity surrounding the mother, as well as all the challenges women face within society;

‘Woman is no longer a synonym for mother’ - p.144 in ‘Time of the Flies’

While the exploration of motherhood is not new for Piñeiro, this more explicitly political approach is. It was interesting to see a writer whom I love play with a form I hadn’t come across from her yet; I was surprised and intrigued by the explorative nature of this novel.

‘Time of the Flies’ was gripping and captivating. Piñeiro writes a flawless thriller every time, creating perfect and enticing suspense on the page. There is always more than meets the eye with Piñeiro, who weaves in deeply complex societal observation and exploration within her novels. ‘Time of the Flies’ intricately explores the landscape of female relationships within friendship and family. She challenges the concept and practicality of motherhood from all angles, frequently giving us a main character who is a ‘bad’ mother. Piñeiro presents us with these mothers, who are unconventional in their role of motherhood, and takes us on a journey to understand the nuances of the relationships they have with their children as well as themselves. Piñeiro often strives to emphasise how these women are human beings first, mothers second. She consistently writes about women who, traditional to a South American society, deeply struggle with the societal expectations of women and motherhood that were forced upon them at a young age.

Inés’s time in prison has left her estranged from her daughter, resulting in her often not viewing herself as a mother at all. The relationship, or lack thereof, between Inés and her daughter is both easy and challenging to understand. Piñeiro uses their estrangement as a vehicle for exploring what defines being a mother, along with our relationship with loyalty and forgiveness.

Despite really enjoying this novel, something felt missing when I finished. Though the story of Inés's life after prison was compelling and captivating, I felt there was a missing backstory on the motivations of the crime she committed fifteen years ago. I then discovered that ‘Time of the Flies’ is a sequel to ‘All Yours’ published in 2005. This explains the impression I felt that it was, in some ways, an incomplete novel. I think it was a mistake from Charco Press to not publish them both, and while that may well be a copyrights issue, I am mildly irritated that I left a Piñeiro novel not feeling as satisfied as I normally do. Everything I have read by Piñeiro I have loved so deeply, and while I did enjoy this, it definitely diverges from what I have read of hers before.

Although I am being critical, because I hold Piñeiro in high regard, I still deeply enjoyed this novel. I flew through it, as I always do with her work, because she is such a skilfully talented writer. She is a great storyteller who writes exceptionally compelling protagonists whose voice you feel deep affection towards. I will always admire Piñeiro’s ingenuity and approach to storytelling, and while different, ‘Time of the Flies’ is no less impressive. I would call this a buy. If you have read Piñeiro before, I would recommend this book. If you haven’t, I would recommend starting with ‘A Little Luck’ and then giving it a go.

‘The Edge of the Alphabet’ by Janet Frame. Toby Withers, a young man with epilepsy, leaves New Zealand after the death of his mother. While on board a ship to England, he meets Zoe, a middle-aged woman looking for a life of meaning, and Pat, an Irishman who claims to have many friends but is careless with the way he treats people. Alike in their alienation from society, all three embark on a new life in London, piecing together an existence in the margins. ‘The Edge of the Alphabet’ is a story about identity and the search for connection in a lonely world.

From the first page I was in awe of Frame’s writing, it is incredibly experimental and dreamlike. When I read this quote, I kept rereading it. I could not believe how extraordinary Frame’s prose was;

‘The bracelet of decay glitters with diamonds. Tiny worms carry lanterns in the storm. At the edge of the alphabet there is no safeguard against the dead’ - p.29 in ‘The Edge of the Alphabet’

Toby, Zoe and Pat are all linked by their experiences of isolation and alienation. They bond over their social inadequacies as Frame explores their inner lives. While perhaps they don’t initially realise it, they are drawn to the way they each hold and conduct themselves. Frame assesses their relationships and positions them within societal expectations, exploring how they all individually don’t fit in. While the characterisation of Toby, Zoe and Pat is light, you understand them all because of the way they share this feeling that they are on the edge of society, not being accepted and struggling to understand others. They share a visceral fear about not succeeding and being understood, but ultimately fail in their efforts to connect to society. They all believe that a life in London is what will solve their dispositions. However, London is not what it seems, as they begin to understand the ‘London streets are paved with gold’ colonial rhetoric is a falsification.

Toby as a narrator, while fleeting, is endearing; in London he believes Piccadilly Circus is a real circus and he inhibits this incredible marvel at the laundry service. He is extremely sheltered but a product of his environment, with some of his family and friends being ableist towards him. ‘The Edge of the Alphabet’ embodies this exploration of how difference is not wrong, that there are many who feel as though they don’t have a place in the world and live at the edge of the alphabet.

Frames' writing is full of palpable emotion, so much so that while I was reading I wondered if this novel reflected struggles from her own life. Her obituary explains that from combined effects of family bereavement and feeling inadequate during her teacher training, Frame had an emotional breakdown which doctors mistook for schizophrenia; a misdiagnosis that kept her in mental hospitals for almost a decade.3

Referring to this period of her life, Frame wrote;

‘I inhabited a territory of loneliness which… resembles the place where the dying spend their time before death, and from where those who do return, living, to the world bring, inevitably, a unique point of view that is a nightmare [and] a treasure’ 4

The intersection between sickness and feeling othered, which is one I am familiar with, is present throughout the novel. Frame was frequently called a ‘mad woman’ by critics to explain her literary creativity and skill. With this understanding of Frame’s personal life, ‘The Edge of the Alphabet’ becomes even more compelling. I admire Frame deeply for writing from the place she did, while others tried to place extensive emotional and physical limits on her. She is a remarkable writer who survived inconceivable challenges in her life.

The plot of this novel is not always discernible, however this does not impact the experience of reading the novel - the prose carries the story. Frame’s use of words is almost poetic as she moves between dreams, reality and alternate points of view. She writes with a commitment to freedom, a desire to write purely from the imagination. I was pleasantly surprised at how much I enjoyed this. I would recommend ‘The Edge of the Alphabet’ and call it a buy!

Headshot by Rita Bullwinkel is the story of the eight best teenage girl boxers in the United States. Told over the two days of a championship tournament and structured as a series of fights, ‘Headshot’ explores and examines what motivates each of these young women to take part in such a physically intense and violent sport. Portraits of each girl emerge as they go head to head with their opponent. The landscape of girlhood; their hopes, dreams and fears, are put in the ring. ‘Headshot’ examines the emotional and physical struggles of being a teenage girl and takes it to the extreme as we watch them compete in an incredibly high-stakes environment.

‘Headshot’ feels perfectly timed to be part of the 2024 summer of sport. Commenced by the release of the film ‘Challengers’ and continued by the events of Wimbledon, The Euros and The Olympics, there is an appetite for understanding the extremity of life as an athlete, and this notion is distinctively explored in ‘Headshot’. Bullwinkel has married two explosive realms, girlhood and boxing, to create a deeply interesting story. She examines the emotions felt by teenage girls, which can be labelled as silly and frivolous, through a traditionally masculine and violent sport. This is genius on many levels from Bullwinkel, but most notably in the relationship to time. ‘Headshot’ reads with exceptional pace and rhythm as the prose breaks with every hit. Bullwinkel places the reader in the alternating consciousness of the girls while they are fighting, to allow us to understand who they are and why they box. While the physicality of boxing is explored, with moves mentioned, the drive of the fight is their internal narratives and emotions. Back and forth we are shown how the girls view themselves and each other, their trauma and aspirations, and how this is perhaps what shapes the fight, rather than physical skill.

Headshot really portrays the severity of life felt as a teenager, dismantling several feminine tropes and exploring the girls in a more animalistic way. Bullwinkel manages to draw together the extensive aspects of girlhood; body image, jealousy and loneliness. The fighting is a vehicle for the girls to express their anger and misunderstanding about what it means to be young. It gives them the opportunity to express themselves when words feel useless. Bullwinkel masterfully explores the intoxicating atmosphere of possibility that exists when you are young. This hunger for life after eighteen; to be older, taken more seriously, to be independent - the uncontrolled ambition is palpable.

‘It seems civil, said Izzy, not to be a half thing, a.k.a. a teenager, for which things are so in-between for so long that it seems impossible to understand the way things really are’ - p.124 in ‘Headshot’

As a reader, it almost invites a sense of melancholy because the passion they feel in the ring, as an athlete but more specifically a teenager, will fade away as they grow up. We know that this desperation for adulthood will transform into a nostalgic longing to be so feisty, carefree and young. These girls are at the cusp of a potential career in boxing - the commencement of being taken seriously. There is a real hunger within the girls, for boxing and growing up. The outcome of this tournament feels as severe to the reader as it does for the characters. ‘Headshot’ transported me right back into the intense landscape of being a teenage girl; one that I, in equal parts, miss and never ever want to feel again.

To be a teenage girl is to feel furious constantly, and ‘Headshot’ embodies that. Bullwinkel’s writing is fierce and animated as she briefly, but seamlessly, drops us into the vigorous and electric universe of a boxing tournament for two days. This book was very easy to read; it was simple and immersive. I’d really recommend ‘Headshot’ and call it a buy. I read it in one sitting, at the edge of my (metaphorical) seat throughout, eager to know who was going to win. It is, at its core, a fun read. Bullwinkel’s approach to describing physical combat interwoven into the personal reminded me of ‘Chain-Gang All-Stars’ by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah - so if you enjoyed Chain-Gang, I think you’d really like this!

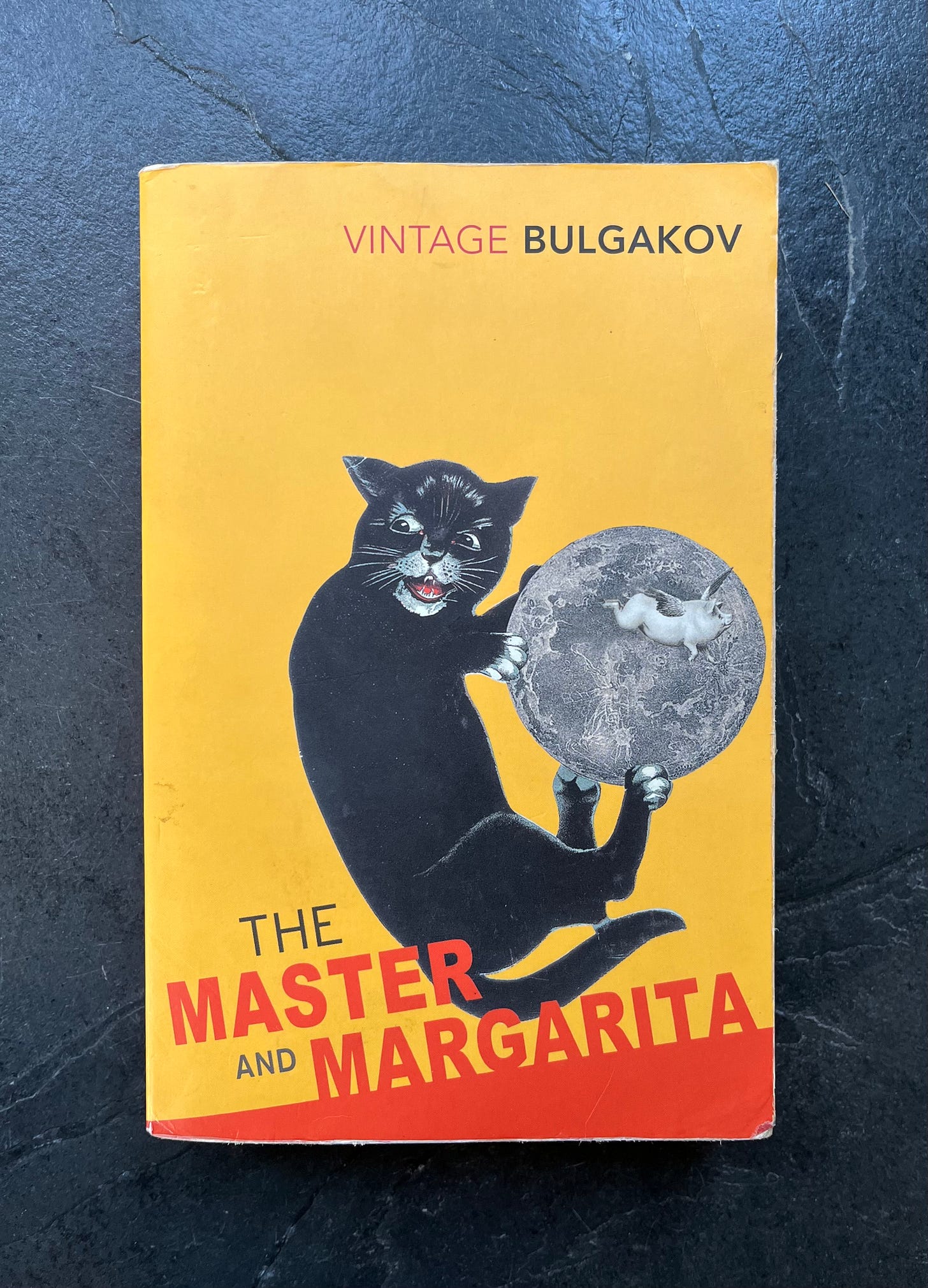

‘The Master and Margarita’ by Mikhail Bulgakov was my classic novel of the month for July. One spring afternoon, the Devil, weaves himself out of the shadows and into Moscow 1930. Trailing fire and chaos in his wake, he is accompanied by various demons, including a naked woman and a huge black cat. When he leaves, those who he has encountered fill up the asylums and the forces of law and order are in disarray. Only one man, the Master, who is a persecuted writer devoted to the truth and Margarita, the woman he loves, can resist the devil’s onslaught.

Written during the darkest days of Stalin’s reign, and published in 1966/7 ‘The Master and Margarita’ signalled artistic and spiritual freedom for Russians everywhere. This book is, in my opinion, one of the ultimate classics. Everyone raves about it and hails Bulgakov one of the great writers of all time. In an effort to be transparent, I was intimidated by this book. It has been on my shelf for a long time, and I have always found a reason not to pick it up. I have resisted reading any reviews on ‘The Master and Margarita’ before I write mine, because I wanted this review to be a reflection of what I thought - and not get lost among all the symbolism and analysis there already exists, in troves, about this book.

The atmosphere of this novel is electric. ‘The Master and the Margarita’ is a complete riot to read, truly exemplifying the definition of madness. Bulgakov’s imagination is phenomenal as he imagines this world where the devil materialises in Moscow and casts spells of black magic among society. The devils meddling is hilarious and imaginative, creating the most outrageous story. This sprawling cluster of magical realism, while good fun, does create a plot that is a challenge to follow. I am not entirely convinced I knew what was going on at times - the novel resembled something akin to three, very different, films playing simultaneously. Some of the threads of these films were easier to grasp than others. Despite being lost a few times, I was always enjoying what I was reading on the page. While this confusion could be due to the translation I read, in many ways I think it's the nature of the novel. In my opinion, even with a confusing plot, this story is one that should be read for the imagination of Bulgakov alone. What he managed to create, especially under totalitarian rule, is exceptional.

Micheal Lockshin’s 2023 film adaptation of ‘The Master and the Margarita’ is causing a backlash in Russia today as state propagandists are attacking Lockshin, some going as far as to advocate for criminal charges to be filed against him.5 This reaction is pertinent and ironic. At its core, the story is about a writer, Master, who is censored by critics and persecuted by the state for his manuscript. A story that served to represent how damaging and wrong totalitarian rule is, that is inherently anti-regime, has not once lost its relevance or messaging within Russia - especially today. This adaptation coincided with the historical moment we are witnessing Russia experience with the invasion of Ukraine. The scenes of this novel, and now film, are becoming more and more timely under Putin’s rule;

‘One has to think of the widespread repression of contemporary writers and cultural practitioners (Boris Akunin, Sasha Skochilenko, Lyudmila Ulitskaya and the many other journalists and opposition figures currently being silenced to see the contemporary echoes of Bulgakov’s text. Just as reading the non-censored, underground version of Bulgakov’s text in the late 1960s because a revolutionary act in and of itself, in Putin’s Russia, going to see Lockshin’s adaptation has become a brave act of revolt’6

Conceptually, ‘The Master and the Margarita’ explores larger moral and ethical principles in relation to the concept and practice of religion. Similarly to ‘East of Eden’ which I read last month, Bulgakov’s novel examines the struggle between good and evil. He suggests that good and evil do not exist in isolation from one another, that they in fact require each other. Furthermore, the novel explores corruption in government, which directly reflects the suffocating climate of life in the Soviet Union when Bulgakov wrote this novel - it is deeply anti authoritarian. In amongst this sprawling, human, landscape of good and evil, the novel suggests there is always a need for connection and compassion. This is articulated within the novel with the theme of enduring love. I did not expect ‘The Master and the Margarita’ to be as romantic as it was. I do not dispute those who describe the story as a romance, because in many ways it is deeply romantic.

The plot of ‘The Master and the Margarita’ is notoriously complex. While I am certain there is enormous and fruitful potential to study the entire text with a fine tooth comb, to make an effort to really understand every single symbolism, I am also an advocate for not overthinking it. Often with classics I think we can get hung up on whether we have ‘got it’ or not. While classics are classics for a reason, they are also just books that have been written to be enjoyed. There were parts of this novel that I did not understand, but instead of getting discouraged, I just kept reading. The atmosphere of anarchy and chaos carries this book. Great religious and political symbolism aside, madness is not something that can, or needs, to be made sense of - inherently it is confusing. The silliness and absurdity of this novel was my favourite aspect. What is there not to enjoy about a human size cat and naked witches wreaking havoc on society?

I would call ‘The Master and the Margarita’ a borrow. I recommend it to anyone who enjoys magical realism and deeply philosophical novels. If you have avoided reading this because you fear it might be too complex - you can do it. Release yourself from the idea that you have to understand it all and enjoy the magical world Bulgakov has created. For anyone who has been lucky enough to study this in an academic environment, please share some of your own reflections with me. I am really eager to hear them!

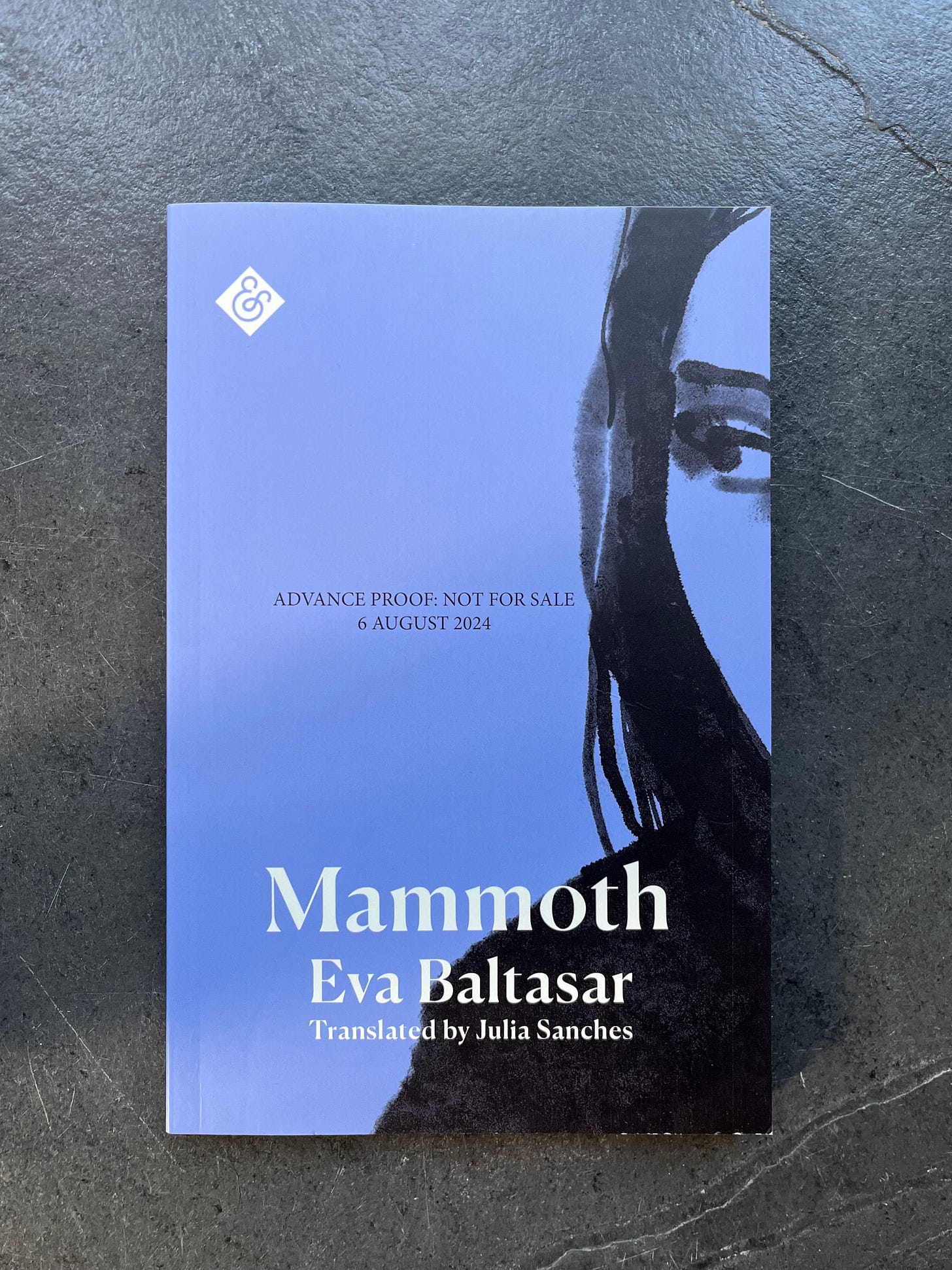

‘Mammoth’ by Eva Baltasar is the tale of a disenchanted queer woman. She is full of a dichotomy of emotions; she is irritated by life, eager to get pregnant and determined to live in a stripped back environment. She seduces men at random, swaps her urban habitat for an isolated farmhouse, befriends a Shepard, nurses lambs and dabbles in sex work - all in pursuit of life in the raw. Her appetite for extremity is all consuming and severe. Mammoth seeks to disrupt her life in the most drastic ways possible. She wants to live, emotionally and physically, on the fringe of society. Described as a ‘howling crescendo of social despair’, Mammoth is pure chaos.

After reading, and loving, ‘Boulder’ last month, I was excited to read Baltasar’s sequel. The themes within ‘Boulder’ and ‘Mammoth’ are very similar. Our protagonists are queer young women who share extreme and unconventional relationships with motherhood. They are unnamed and inhibit these strong, powerful and solitary metaphors of a boulder and a mammoth. Last month I said Boulder was the least maternal fictional character I may have ever read. That statement is now subject to change, as Mammoth is even less maternal. I was unsure how Baltasar could make ‘Mammoth’ even more disturbing than ‘Boulder’ - but she did. Mammoth has this real appetite for power play that is, at times, extracting and exploitative. She is fascinated by the extreme and finds a deep thrill in outrageous environments; sleeping with men, leading a life of rural exile on a mountain and extreme weather.

‘I go through hell and find it thrilling. I can’t get enough of this feeling - of my heart pulling the trigger and shooting’ - p.31 in ‘Mammoth’

Mammoths' compulsion to push her mind and body to the extreme manifests most in a hunger to be pregnant. She views pregnancy as this opportunity to push her body, carrying this alien like life inside her. She does not view pregnancy as this opportunity to create life or family, but instead as a self serving radical challenge. It is unsettling to read about pregnancy in such a sinister and selfish way. Deeply poetic, Baltasar’s writing is piercing;

‘I wait for the tornado as if I were going to marry it. I want life to mow me down, to feel its hand on the nape of my neck. For it to make me swallow dirt while I breathe. Because - because feeling alive means shouldering the burden, now that I know can bear the weight’ - p.71 in ‘Mammoth’

Baltasar’s ability to write such horrifying women is just remarkable; they are grotesque and unhinged. ‘Mammoth’ made me gasp, cringe and laugh as I devoured this novella in one sitting. Mammoth inhibits a level of unforgiving cruelty, while Boulder was much more reflective and pensive. This makes Boulder easier to identify with as she struggles with communicating how she feels, rather than Mammoth who is a more impenetrable narrator. Although I preferred ‘Boulder’, this was still good. Baltasar’s short fiction is so deeply impressive and weird. The characters and atmosphere she creates in less than one hundred pages is outstanding. Despite being short, the stories are rich in thought provoking themes.

‘Mammoth’ unflinchingly explores modern life and the human condition. I think it might be the most chaotic and weird book I have ever read. If you have read ‘Boulder’ and are looking for Baltasar to take her writing to a new extreme, I would recommend this. I would also recommend it to anyone who enjoys outrageous and unhinged stories. I would call ‘Mammoth’ a borrow!

Enter Ghost by Isabella Hammad follows the story of Sonia Nasir, an actress, who is returning to her family’s homeland. After years away, her marriage ending, and a disastrous love affair, Sonia returns to Haifa to visit her sister Haneen. Upon her arrival, she finds her relationship to Palestine fragile and conflicted. Sonia meets Haneen’s friend Mariam, a local director, who is in need of an actress for her production of Hamlet in the West Bank. Sonia reluctantly joins the production and finds herself rehearsing with a dedicated and competitive group of men. However, as opening night draws closer, it becomes clear just how many obstacles, personally and politically, stand before the cast. Amidst it all, the life she once knew starts to fall away to the exhilarating possibility of finding a new self in her ancestral home. It is a story about family, history and identity.

‘Enter Ghost’ has been on my radar for a while, but

’s review is what really compelled me to buy it. She described it as the ‘perfect literary fiction’ and ‘deeply layered and meaningful’ in her review. I am here to echo her and all the praise she gave this novel. ‘Enter Ghost’ was the most outstanding and compelling book I have read in a while.From the beginning, ‘Enter Ghost’ immediately communicates how politicised Sonia’s life is by the virtue that she is Palestinian. The narrative immediately immerses us in the realm of identity politics, beginning with a scene where Sonia is questioned by her taxi driver as she departs the airport;

‘Jewish?’ I pretended I hadn’t heard. I think he had guessed I was Arab or I doubt he would have asked. I didn’t like these dances between drivers and their passengers, testing origin, allegiance, and degrees of ignorance.’ p.3 in ‘Enter Ghost’

While Sonia is our protagonist, the novel immediately conveys that she is a vehicle for telling a much bigger story on the behalf of Palestinians. Hammad skilfully communicates both the political complexity of the situation, as well as the simplicity of it. With Sonia’s initial return, through her character we feel a confusion surrounding Palestine; the politics, the history and the present day. She is an outsider despite Palestine being her ancestral home. Sonia struggles as she feels she doesn't know ‘enough’ about what is going on, that she is perhaps missing cultural nuances by not living there or speaking fluent Arabic. However, as the novel draws to a close, Sonia realises that spending time with the cast communicates the oppression and violence that is being enacted against Palestinians. They humanise the highly politicised conflict. Sonia comes to represent how this disconnect from Palestinians, which is pushed by news cycles and ideological discussion, detaches people from an ability to understand the suffering of Palestinians from a humane angle. 7

‘Enter Ghost’ being formed around a production of Hamlet in the West Bank was genius. Hamlet creates an avenue for Hammad to discuss the relationship between performance, political protest and power, as well as the history of theatre as a politicised art-form.8 It creates an atmosphere of tragedy and understanding for those who are not familiar with Palestine. There is tragedy on stage, among the cast and within where they choose to perform the production. Hammad is telling a layered and complex story in an incredibly intelligent way. ‘Enter Ghost’ includes playtex on the page that isn’t from Hamlet but dialogue between the actors. This mirrors the tragedy experienced within the cast in a variety of ways. It was brilliant; incredible prose, concept and execution. The momentum of the cast working towards the production of Hamlet gives the story a unique trajectory.

I talk extensively about how much we can learn from fiction, and how often people underestimate it as a tool for learning. While non-fiction and reporting are crucial for understanding details and events, fiction imbues these facts with emotion and a deeper sense of humanity. ‘Enter Ghost’ is a perfect example of this, injecting soul into the often incredibly sterile nature of reporting; it humanises events and creates the emotion that is avoidant in the news. Hammad gives an exceptional insight into contemporary Palestine, of the everyday experiences of those who live there. The emotion and empathy is tangible and is what makes ‘Enter Ghost’, and novels as a whole, such a rich place to learn and understand. The political discussion is easy to engage with. It does not alienate the reader from the story, instead meeting them in an uncomplicated way - there is no prior assumption of knowledge from Hammad here.

‘And yet this tiny place occupied such varied terrain - desert, sea, mountains - and such a large space in the global mind’ - p.165 in ‘Enter Ghost’

Alongside the exceptional political commentary within the novel, ‘Enter Ghost’ is also a tender and honest exploration of familial relationships. Sonia’s family is not perfect, and to see this discussed on the page sincerely and transparency was lovely to read. Equally, Sonia’s relationship with her own identity was incredibly compelling. Her experiences with love, her career and family were imperfect; Sonia is a protagonist who is deeply human. Various aspects of her life are not going as planned, as she struggles to understand how to navigate them. Despite being quite a detached narrator, I felt a real affection towards her throughout the novel.

‘Enter Ghost’ is a deeply engrossing story about the relationship between art, politics and family. I was incredibly captivated the entire time I was reading. I would, without a doubt, call this a buy and heavily recommend it.

said it was a perfect literary fiction and I agree, it is a perfect literary fiction. A wonderful and powerful read that I have missed ever since I put it down.And that concludes my July Reads! My favourite read of the month was ‘Enter Ghost’.

My first read of August is ‘The Lacuna’ by Barbara Kingsolver. I was initially scared by the length of this book (670 pages) but I wanted to read it because I loved ‘Demon Copperhead’ so much last year. I haven’t read any other Kingsolver and I want to become more acquainted with her writing. Does anyone have a favourite Kingsolver novel they would recommend?

I started ‘The Lacuna’ last week and I actually finished it this morning - making it a mostly July barely August read (a miscalculation of my reading speed on my part - the review will come next month). Because of this feel I should tell you my second read of August, which is ‘The Summer Book’ by Tove Jansson.

August is ‘Women In Translation’ Month, so Jansson’s book is perfect! I aim to write a newsletter in the coming weeks of some of my favourite translated books written by women.

In the mean time, you can get some recommendations from the post I did for WITM last year:

☞ In book news, The Booker Prize released their 2024 longlist this week. ‘Headshot’ from this newsletter has been listed, which I think is deserving!

I have a copy of ‘My Friends’ by Hisham Matar on my shelf, recommended to me by my friend Margo from

- so I guess I need to read it soon!From the list I am intrigued by:

I have wanted to read ‘James’ by Percival Everett for a long time but have been waiting for it to come out in paperback in the UK - but perhaps I need to forgo that plan.

Let me know your thoughts:

❀ What have you read and enjoyed in July?

❃ Have you read any of these books? What did you think?

☼ Have you read a good book lately you think I, and the readers of ‘Martha’s Monthly’, would enjoy? Leave a recommendation in the comments for us all to enjoy <3

Thank you, as always, for reading.

Let me know if you found a book that interests you!

Happy Reading! Love Martha

Share this with that friend who is always looking for books to read! It will make you look cool and well read.

Catch up on what you might have missed:

If you weren’t around last year and are interested in what I was reading in July 2023, click here.

If you enjoyed this and want more, why not subscribe? Martha’s Monthly is a newsletter dedicated to bringing you thought-provoking, translated and diverse book recommendations.

Subscribing is the best way to show me you enjoy my work!

Sentence lifted from this article by Reading In Translation about Ginzburg: https://readingintranslation.com/2024/07/15/reading-natalia-ginzburg-in-the-twenty-first-century/

Some quick facts on Ginzburg and the life she lead (spoiler it’s insane): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natalia_Ginzburg

Frame’s Guardian Obituary where I got this information from: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2004/jan/30/guardianobituaries.booksobituaries

Quote from the Guardian Obituary: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2004/jan/30/guardianobituaries.booksobituaries

I got most of this information from this article: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20240430-the-master-and-margarita-the-russian-box-office-hit-that-criticised-the-state#:~:text=It's%20hard%20to%20imagine%20that,box%2Doffice%20hit%20in%20Russia and this interview with Lockshin: (if you are interested in the novel, or just Russia in general, I would recommend this video! It’s really insightful about the current cultural landscape in Russia under Putin)

This quote is from Lit Hub: https://lithub.com/why-a-new-adaptation-of-the-master-and-margarita-is-setting-russian-society-aflame/

Sentence adapted from a line found in this interview with Hammad about the novel: https://womensprize.com/in-conversation-with-isabella-hammad/

OK... Joining the Enter Ghost club. And it took me a minute but... omg... that title is brilliant!!!

Such a good bunch! I finished reading Enter Ghost earlier this week and echo your thoughts on it. I was really impressed and I'm looking forward to reading more Hammad.

I've been meaning to pick up some Claudia Piñeiro for a while now. Maybe next time I'm in Spain I should try and get my hands on a copy in the original language. I tend to favour reading in English and I think that's why I've kept pushing her off for a later date.

I've only read two Kingsolver books, so I don't have a good overview over her work either, but I would highly recommend Prodigal Summer by her!