Welcome back to Martha’s Monthly, January Reads edition! January was slow, as it always is, and I felt that in my reading. Somewhere between the never ending very grey English skies and it being January, my reading month felt average. Two of the books I read this month were gifts and they were the ones I loved the most. Perhaps I’m losing my touch. I’m kidding! I could never. I loved one book I chose myself, so all is not lost.

My January reads included authors from Ireland, India, Jamaica, Argentina, Japan, Ghana and Sweden. To see the translated reads from January on Martha’s Map, click here.

Without further ado, here are my January reads in their buy, borrow and bust format. For those who are new, buy, borrow, bust is my recommendation key. Buy = I immensely enjoyed and heavily recommend this book. Borrow = I think this book is still well worth a read and I’m glad I read it. Bust = I wouldn’t recommend this book from my own reading experience.

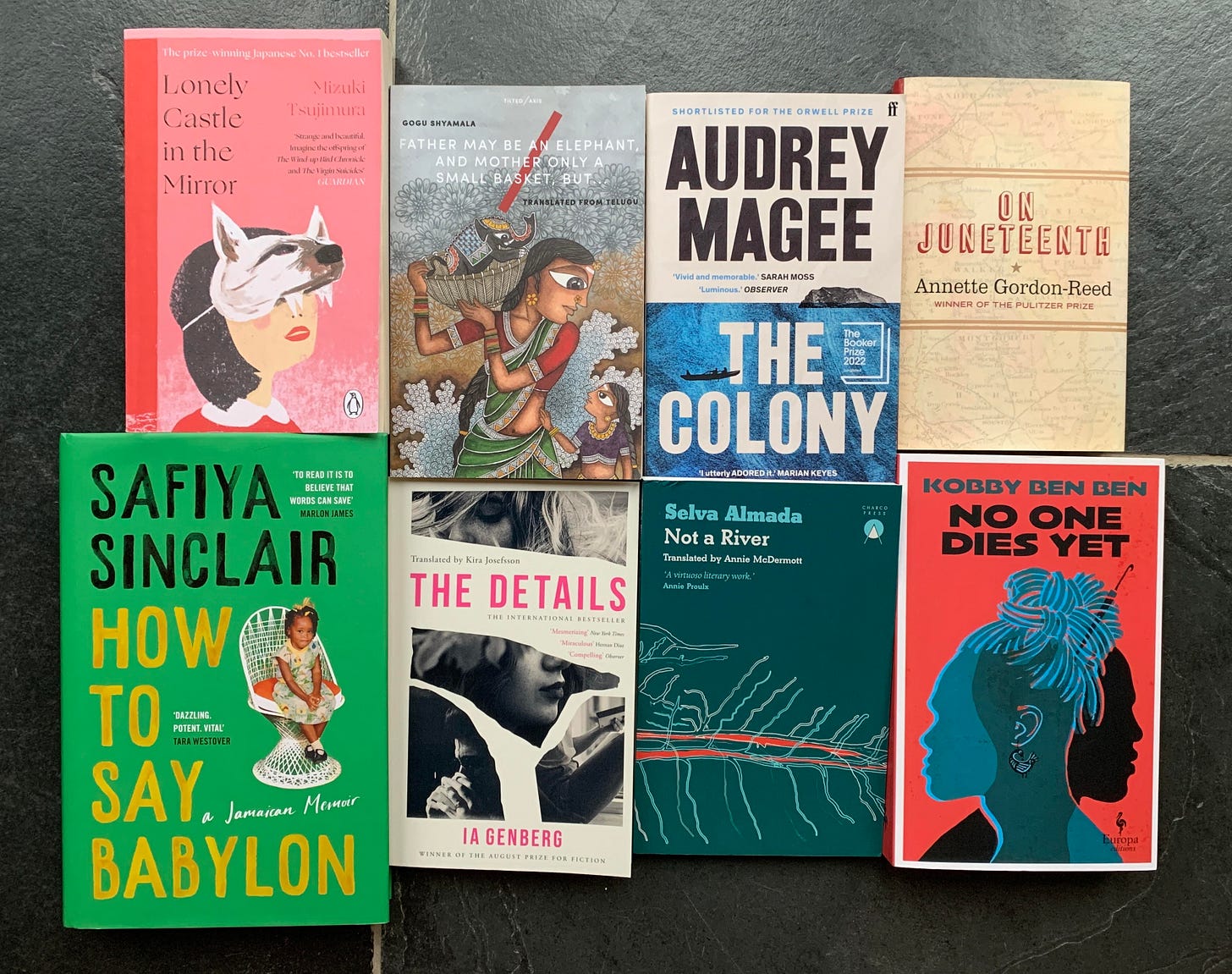

‘The Colony’ by Audrey Magee was my first read of 2024. Set in 1979 on an unnamed remote island off Ireland’s Atlantic coast. On this rock, three miles long and half a mile wide, traditional life and the Irish language are receding into extinction. Amidst the ongoing Troubles in Ireland, two outsiders journey to the remote island, driven by personal quests and ambitions, irrespective of the potential consequences for the local residents. Mr Lloyd, an English painter, decides to travel to the island by boat without an engine. He wants to have an authentic experience, to be changed by the island's serenity. He doesn’t know that a Frenchman follows close behind. Jean-Pierre Masson (JP) has been visiting the island for many years, studying the changing language of those who call the island home. He is fiercely protective of their isolation and deems it essential to exploring his theories of language preservation and identity.

While consistently fighting over what is best for these people, Mr Lloyd and Mr Masson fail to consider that the people on the island have their own views on what is being recorded and what ought to be given in return. Three generations of the island's descendants; Bean Uí Fhloinn, her widowed granddaughter Mairéad and her fifteen-year-old son James wrestle with their own values and desires during the summer of their visit. As we are submerged into the isolated world of the islanders through the eyes of Mr Lloyd and Mr Masson, violence continues to escalate all over Ireland. Through an expertly woven dual narrative between the locations of the island and the mainland, Magee creates an unflinching political critique of the long, seething cost of imperialism, contrasting merciless violence with the merciless environment of the island.

‘The Colony’ is a parable that celebrates beauty and connection while reckoning with the ruptures of independence, power and influence. This read was deeply thought provoking and unique. Magee situates the Troubles within a post-colonialism framework. Through an initially unassuming narrative structure, Magee explores the damaging effects of colonisation and its legacy in a very subtle way. The imposing characters of Mr Lloyd and Mr Masson represent cultural appropriation, exploitation and the impact of imperialism on the demise and development of traditional language. These well meaning visitors reflect colonial legacy and a neocolonial rivalry. They hate each other, and both think that they know what is best for the island and those who live there.

It’s my [Micheál] language, JP. I can use it as I please [...]

It’s theirs to kill, said Lloyd. Not yours.

Masson shook his head.

You can’t speak on this, you have spent centuries trying to annihilate this language, this culture.

[...]

France is no better, said Lloyd. Look at Algeria. At Cameroon. At the Pacific Islands.

You're deflecting.

Lloyd shrugged.

This is about Ireland, said Masson. About the Irish language.

And do the Irish have a say, said Lloyd, in your great plan for saving the language?

The English don’t, said Masson.

This argument between Lloyd and JP is deeply ironic and a strong metaphor of the relationship between France, Britain and Ireland. You also get a taste for Magee’s structure and prose. It is a flowing narrative voice, with points of view shifting within the same sentence or paragraph. Through a lack of speech marks and punctuation, the boundary between thought and speech is permeable, to represent how most characters are multilingual. The exploration this story gives to the ever evolving development of language was really interesting, highlighting what language can represent.

The ending of the novel is poignant and as a reader I felt a deep sense of fear for these islanders about what will happen to them after what JP and Lloyd have done. Through assuming a need for their presence on this island they have monumentally impacted and shifted their way of life. As the narrative jumps between the island and the mainland, a quiet but impending sense of doom clouds over the book. Is the island destined for life on the mainland? It carries a bitter taste, suggesting that even the most isolated communities have been and will be impacted by imperialism, it is only a matter of time.

I really really loved this book. I was initially apprehensive because of the narrative structure and postmodern vibe. But it grew into a highly nuanced, introspective and engrossing tale where the island is a symbol for Ireland, colonialism and humanity. I would completely recommend this book and call it a buy. I read a lot of historical fiction and this was very different, but I liked it a lot. We can now confirm my friend does know me very well for giving me this book thinking I would love it - I did.

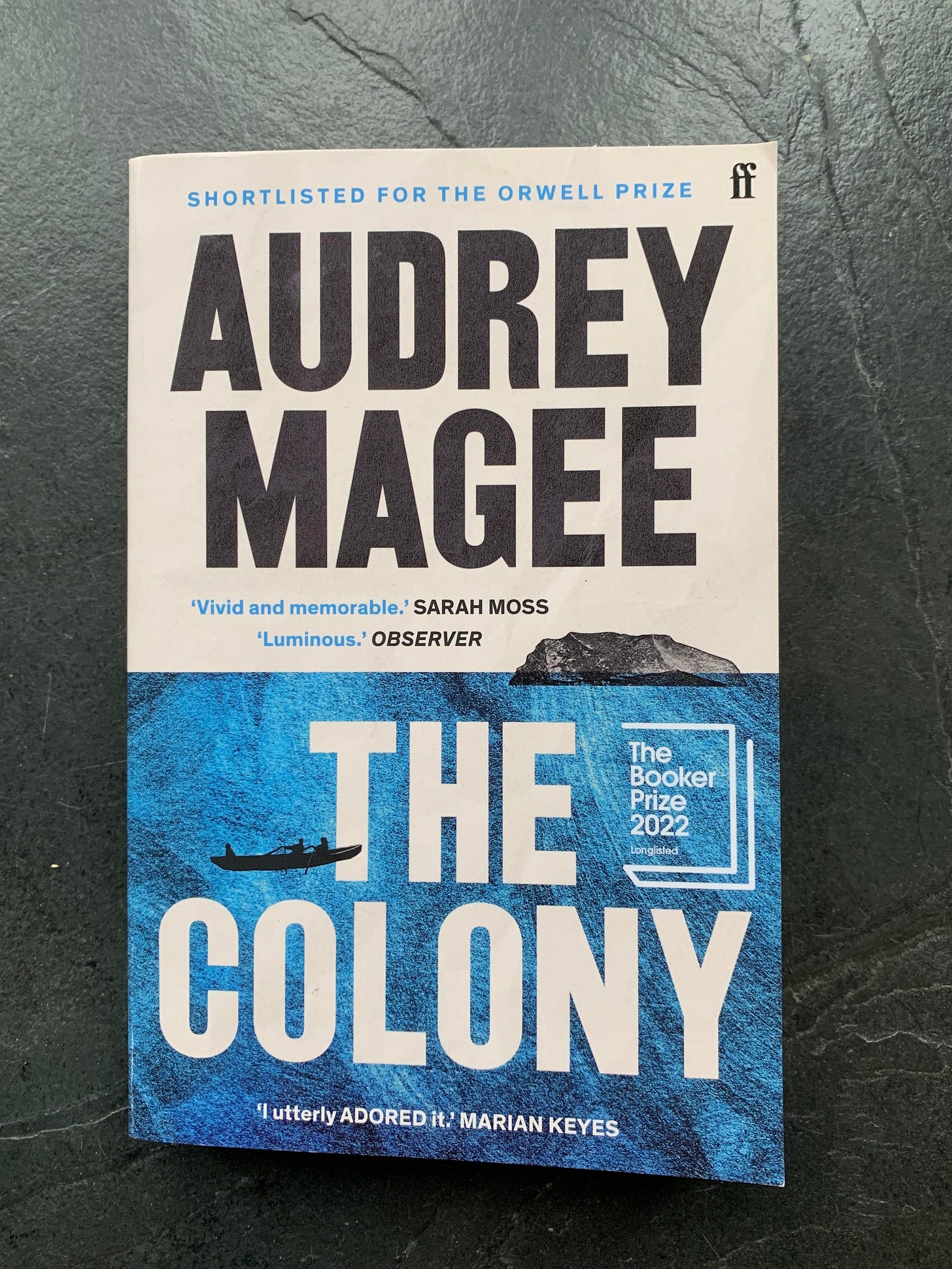

‘Father May Be An Elephant, And Mother Only A Small Basket, But…’ by Gogu Shyamala. Translated from variants of Telugu, these short stories of childhood in a rural Indian village dissolve the borders of realism, allegory and political fable. Gogu Shyamala is a philosopher, poet, prolific story writer and hailed as a landmark in Telangana Dalit literature. This is a collection of stories about relationships; between the different castes that make up a village, between an individual and the wider community, between identities and the seasons of the land. With threads of feminist philosophy running through, they are stories of ingenuity and defiance.

As with most short story collections, there are some I enjoyed more than others. But here are the ones that I liked the most. ‘Jambava’s Lineage’ explores the experience of what life is like for the women of the Madiga caste who are performers.1 One of the dancers is questioned by a young girl as to why they are treated the way they are. It was touching and heartbreaking to read how this woman was navigating attempting to explain the caste hierarchy to a child. ‘The Village Tanks Lament’ is a story told from the perspective of a well where we learn about who cares for the land and who cares for those people. ‘Obstacle Race’ tells the story of the relationship between castes, schooling and education. We meet a boy who is allowed to go to school with a predominantly different caste to him, and he is treated poorly. It explores that no matter how talented he is in the classroom, he can never escape his birth destiny.

My favourite short story was ‘Raw Wound’. It is about a girl who gets sent to school to avoid becoming the village jogini.2 Her family tries to protect her from a predestined fate, and the implications this has on their life is astonishing. It was a horrifying and eye opening story to the severe limitations of some castes, as well as the unwavering traditions that lie within some caste communities. I had never come across the term ‘Jogini’ before and to learn what it meant and entailed astounded me.

Overall, I enjoyed about half of these stories in the collection. Some were incredibly interesting and well done, while others I fear were slightly lost in translation. I learnt so much more about caste dynamics which I enjoyed and appreciated the immersive tone of the whole collection into the lives led by those who reside in the poorer and less fortunate castes that make up India. I would call this a borrow. If I am being completely honest what made me pick up this book was the cover - because it’s stunning.

‘How To Say Babylon’ by Safiya Sinclair is a powerful memoir about the struggle to break free from rigid Rastafarian upbringing. Born in Montego Bay to Rastafarian parents in 1984, Sinclair takes us on a journey of her lineage and relationship with Jamaica. Safiya’s father is a volatile reggae musician and strict believer in a militant sect of Rastafarianism. He held strict patriarchal views and repressive control over her and her siblings' childhood. He believed in railing against Babylon and the corrupting influence of the immoral Western world. ‘Babylon’ refers to the sinister forces of Western ideology, colonialism and christianity. Safiya and her siblings lived in near poverty and cut off from their extended family. Her father became obsessed with impurity and to protect the purity of the women in their family he forbade almost everything; no short skirts, make-up, no opinions, nowhere but home and school, no friends and no future but this Rastafarian path. For Safiya’s father, a woman's best virtue was obedience. Sinclair describes her house as ‘a new gospel, a new church, a new Sinclair sect.’

As the eldest, Safiya had the most exposure to watching her father’s persona dramatically change. Initially she believes her and her brother are equally admired in their fathers eyes. But as she grew into the woman she was always destined to be, it became strikingly clear to her that the abuse he gave her mother would soon be projected towards her. Raised in a world dominated by her father’s absolute and isolating rule, she experienced escalating conflicts with him. As Safyia watched her mother struggle voicelessly for years, she increasingly used her education as a sharp tool with which to find her voice and eventually break free. While Safyia feeds her burgeoning independence with books and poetry, her fathers rage and paranoia explodes in increasingly violence. ‘How To Say Babylon’ is a reckoning with the culture that initially nourished her but ultimately sought to silence her. It is a reckoning with patriarchy and tradition, as well as the legacy of colonialism in Jamaica. Safiya tells an unforgettable story of a girl's determination to live her life on her own terms and carve out her own identity.

This memoir was absolutely sensational. In seeking to understand the past of her family, Sinclair takes the reader inside a world of Rastafarianism that is little understood to the outside world. I think all my readers understand by now how much I love learning new things when reading, so I was fascinated to learn more about the history of Rastafarianism in Jamaica - a religion I know absolutely nothing about. Sinclair paints a vivid picture of the social and political landscape that Rastafarianism was born into in Jamaica in the 1930s and the volatile and cruel relationship between Rastas and the British government during empire.

The British government launched barbaric and senseless violence towards the Rastas. In 1963 a group of Rastas refused to relinquish the farmlands they lived on in a government seizure, so Prime Minister Alexander Bustamante ordered the military to ‘Bring in all Rastas, dead or alive!’. This triggered a devastating military operation where Rasta communes were burned and more than 150 Rastas were captured, imprisoned and tortured, and an unknown number were killed. It is incredibly crucial for Sinclair to bring in the legacy of the empire and history of Rastas in Jamaica into her memoir. It gives such an essential history for coming to understand the perspective of her father and how he ended up becoming so extreme in his beliefs. It helps the reader understand how deep the scars of imperialism run within the communities it affected first hand.

Safyia describes her father as using reggae to express;

‘His own helpless rage at the history of black enslavement at the hands of colonial powers and his disgust at the mistreatment of black Jamaicans in a newly postcolonial society’.

Sinclar does not demonise her parents, but instead takes on an honest and vulnerable approach to understanding them. Sinclair does not seek to label her parents as bad, but to showcase their own complex personal history. It is incredibly admirable to be able to do this in the context of such strict religious upbringing. Sinclair’s childhood was also characterised by abuse outside the home, from people other than her father. Sinclair discusses her experience with going to an all white girls school; what being a Rastafarian girl was like in Montego Bay heavily populated by resorts, colonial legacy and tourists. To read about how alone Sinclair felt as a child was heartbreaking. Time and time again she tells us of utter despair, sinking into deep depression and feeling utterly worthless. It is a testimony to her own sense of self that she found a way to nurture her creativity and the strength she needed to disobey her father.

This memoir is incredibly lyrical and poetic. Sinclair is a poet so her ability to employ words is unsurprising, but to make a memoir a literary masterpiece takes unbelievable skill. It is incredibly hard to write so beautifully and objectively about one's own life. It is a story of immense sadness and immense hope. I now really want to read some of Sinclair’s poetry like ‘Cannibal’ and ‘Catacombs’. Exuding self discovery and empowerment, this was one of the best memoirs I have read. It was a treat to be allowed into Safyia’s world and to learn about the immense hardships of her early life. Sinclair lays bare everything that happened to her and how she was able to overcome it. It is incredible. I would absolutely recommend this book and call it a buy.

Inspired by the parallels it illuminated between her and Safyia’s family life, my friend

wrote an essay reflecting on ‘How To Say Babylon’. It is sensational and if you are at all interested in reading the memoir I’d recommend reading Laleh’s essay. Just as Sinclair was inspired by the poem ‘The Butterfly’, Laleh was inspired by Sinclair. Therein lies the beauty of the written word - what we learn from it and what it can help us see within ourselves.‘Not a River’ by Selva Almada. This novella explores masculinity, guilt and irrepressible desire. On a hot, motionless afternoon three men go out fishing; Enero, El Negro and their dead friend’s teenage son. They are returning to a favourite spot on the river, despite their memories of a terrible accident there three years earlier. This intimate and peculiar moment connects the lives of these three men to the lives of the local inhabitants. As the long day passes, they drink, cook, talk and dance to try and overcome the ghosts of their past. But they are outsiders amongst the local islanders. The forest closes in and violence seems inevitable. As night approaches and tensions rise, Enero and El Negro return to the charged memories of their friend who years ago drowned in the same river.

Just like the integral linguistic style of ‘The Colony’, ‘Not a River’ is a narrative where the use of language, structure and punctuation mould the story. The prose flows like a river; the river where the terrible accident happened three years earlier. With no punctuation, speech marks or chapters there is a lack of sign posting for the past and present, living and dead, making the experience of reading hazy and confusing. This comes to represent the insular and unsettling aspect of small village life; slightly suffocating and full of secrets and lies. The story also perpetuates this idea of a small village's inability to deal with tragedy, characterising the refusal to move on. These themes also connect to the toxic masculinity explored within the story. There is a violence emerging throughout the story but you are completely unable to decipher where it is coming from, further adding to this central feeling of confusion.

This was really clever from Almada and made clearer to me by the translators note at the end of the novel;

‘Removing everything extraneous - speech tags, chapter divisions, even most of the words - to bring her prose to the very brink of poetry. [...] The line breaks and lack of chapter divisions make the text itself river-shaped, its short sentences lapping at the silence like waves on the shore’

Almada is an author that approaches the act of writing as an art. The experience of reading ‘Not a River’ was confusing, frustrating and felt a bit like a fever dream. Once I finished reading, and read the translator's note, I was able to admire the novella as a whole. I came to understand the story and the structure in a completely different light. I really enjoy being challenged by authors now and again in this way as I think it really confronts the preconceived ideas and perceptions of how stories can be told. After finishing this book I discovered this was the final book in a trilogy about masculinity in rural Argentina. So I will be retreating backwards and reading the first two to get a better understanding of Almada’s exploration of masculinity. The other two works are ‘The Wind that Lays Waste’ and ‘Brickmakers’. I would call ‘Not a River’ a borrow. If you enjoy poetry, you will really be able to appreciate what Almada is trying to achieve in this novella.

‘Lonely Castle in the Mirror’ by Mizuki Tsujimura. After such an artistic, albeit suffocating novella, as well as a deeply moving memoir, I was craving a more simple and fast paced story. In a neighbourhood in Tokyo, seven young people wake up to find their bedroom mirrors shining. Placing their palms on the surface they discover a portal into another world that offers temporary escape from their lives. Passing through the mirror they are taken to a magical castle which becomes their refuge. In the castle they also meet their taskmaster; Wolf Queen. The students are tasked with locating a hidden key that will allow whoever finds it to be granted a wish. Once the wish is granted, the castle will vanish, along with all the memories they have of their adventure. And if they fail to leave the castle by 5pm every afternoon, they will be eaten by the Wolf Queen. As they struggle to abide by the rules of the game, and each other's emotional boundaries, the characters are ultimately set free by the power of friendship, empathy and sacrifice.

This was a very sweet story about anxiety and the struggles of adolescence and the importance of being there for one another. I have found Japanese literature to often have strong moral messaging about community, connection and how people should work together for the greater good, and these themes are definitely found in this story. The mystery unfolded in a captivating way as the students began to discover what binds them, and it was very heartwarming to witness their growing friendship and confidence. I thought I had the story sussed out, but I was proved wrong as the second half of the novel took me by complete surprise. Unpredictability is always key, especially in fantasy so I was pleased that the story took a twist. It was a very well written mystery where all the puzzle pieces fitted together seamlessly by the end.

‘Lonely Castle in the Mirror’ is not a story of impressive linguistics or prose, which are usually my favourite kind of books, but that is not to say it isn’t a well done story. It was a sweet and fast paced read, a perfect palette cleanser book to break up all the devastating and emotional books I like to read. I don’t have much more to say about it than it was nice and I feel like most people could enjoy this. I would call it a borrow. Palette cleanser books do have a role to play in this world and even I, a gut wrenching, depressing and emotional story connoisseur, recognise that. I wanted something simple and fast paced and this definitely satisfied that. I think if you wanted to read a book in a day, or over a long journey, I’d point you towards this.

‘On Juneteenth’ by Annette Gordon-Reed. Weaving together part Texan history and part memoir, ‘On Juneteenth’ provides a historian’s view of the country’s road to Juneteenth.3 Recounting its origins in Texas and the enormous hardships that African-Americans have endured in the century since, from Reconstruction through Jim Crow and beyond. Gordon-Reed argues that the stories of cowboys, ranchers and oil men have long dominated the lore of Texas.

A native Texan, she seeks to craft an authentic narrative of her home state, highlighting the pivotal role of African-Americans from the earliest times to the 1865 abolition of slavery. Gordon-Reed argues how integral African-Americans are to the story of Texas. They shared the land with Indigenous people who faced their own conflicts with European-Americans, creating a volatile racial tableau whose legacies are still haunting. Gordon-Reed also shares her own experience as one of the first black students to attend an all white school. She shows how the contentious history of the ‘Lone Star’ state can provide us with a new perspective on America's past and possible future. As America only recognised Juneteenth as a federal holiday in 2021, this book is a stark reminder that the fight for equality is exigent and ongoing.

‘On Juneteenth’ offers thought provoking and insightful explorations of race, identity and American history. I truly knew nothing about the racial and social makeup of Texas so this book was educational and interesting.

‘No other state brings together so many disparate and defining characteristics all in one - a state that shared a border with a foreign nation, a state with a long history of disputes between Europeans and an Indigenous population and between Anglo-Europeans and people of Spanish origin, a state that existed as an independent nation, that had plantation based slavery and legalised Jim Crow.’

Gordon-Reed explores how ‘Texas is a white man’. She discusses the relationship between patriarchy and race, commenting on how Texas being personified as a white man directly comments on interplay with race and gender that existed within the state. ‘On Juneteenth’ aims to dispute the preconceived notion, and remind us of the very colourful history that Texas has. Native peoples came to Texas during the Ice Age to quarry Alibates flint. There is evidence of early settlements and Indigenous people all over the area.

I particularly enjoyed reading Gordon-Reed's mixed media approach. Throughout her commentary she includes references to songs, films and court cases which help us further understand the tonality of the time period is discussing. Such as the Billy Jack franchise that came out in the 1970s, where the title character was a mixed raced Native American man, and how odd it was that people loved this movie while still holding hostility towards Native Americans. What I enjoyed the most though was Gordon-Reeds own memories and stories from her childhood as a black girl growing up in Texas. At times I wanted more of her memoir vignettes and less of the history of the state, as I expected ‘On Juneteenth’ to be more memoir than it actually was. I appreciated her acknowledgement that the way she was treated as the only black child in school was down to her educational capability, and believes that if she was not as gifted it would have been a totally different experience for her.

While reading this it made me think of

newsletter a few months ago where he shared a ‘Texas Map’ from 1951 about how Texan’s view themselves. It is satirical, but a lot of what Gordon-Reed discusses in her book can be seen in this map, with the Map saying ‘Texas is so rugged that the wild Indians just gave up and disappeared’. This directly reflects what Gordon-Reed mentions about the presence of Native Americans in Texas, how they were treated and their experience with racism. It was fun to be able to create this connection between a source that so clearly articulates some of the attitudes and perceptions of Texas that the Texans have that Gordon-Reed was discussing. Reading this book and identifying attitudes in this source brought me right back to my History degree days.I would call ‘On Juneteenth’ a borrow. It was incredibly interesting and I learnt a lot about a state I probably would otherwise not have known. I am much more of a memoir reader than a non-fiction reader so I think I wanted this to be more memoir orientated. However, this does not take away from the very well researched and constructed book about Texas’ history that Gordon-Reed put together. At least I tried something new. And now I know much more about Texas than I otherwise would have, putting me in the perfect position for an oddly specific quiz about Texan history.

‘No One Dies Yet’ by Kobby Ben Ben. 2019 is The Year of the Return. It has been exactly 400 years since the first slave ships left Ghana for America. Now, Ghana has opened its doors to Black diaspora, encouraging them to return to the land of their ancestors. Elton, Vincent and Scott arrive from America to visit preserved sites from the transatlantic slave route and to explore the country’s underground queer scene. For their trip they have two combative tour guides; Kobby and Nana. Kobby is their way into Accra’s privileged and queer circles, while Nana is the voice of village tradition and religious principle. Kobby and Nana are our narrators. The pair have a tense relationship which sets the tone for a shocking and unsettling tale of murder. Through an amalgamation of genres, ‘No One Dies Yet’ tells the story of opportunistic murder.

Whilst researching to better understand the ‘Year of Return’, I found an article by Akua Antwiwaa called ‘The Year of Reckoning’. Antwiwaa discusses what happens when discourses about slavery, tourism and celebration come together. She argues how the year of return is not a fact that has been waiting to ground black diaspora identities and critiques the profit motive behind these celebrations, asserting that the government saw it as a tourism boost opportunity, rather than instituting a transformative relationship between Africans and its diaspora. It is mainly the black cultural elite with the economic means who are able to travel and attend these events. Antwiwaa articulates how this celebration offers little for the majority of poor and working class Ghanians and refuses to examine the legacies of empire and class warfare that have constructed Ghana today. Antwiwaa asks; What truly is the value of a year of return if it only exists for the elite? 4 I strongly recommend reading the whole article. It is really interesting and discusses the inherent themes to ‘No One Dies Yet’.

‘No One Dies Yet’ is a story with unique commentary on reparations, justice and colonialism. It is centred around black diaspora identity, which is an identity I haven't come across being explored before. The story discusses in great depth the emotions that surround black diaspora, exploring the tension between black Africans and descendants of black slaves living outside Africa. ‘No One Dies Yet’ asks the questions of what do black diaspora owe Africa? And what does Africa owe black diaspora? I found this really interesting and thought the book tackled the topic with a lot of nuance and understanding as both identities are presented to struggle with the other.

We see this struggle articulated within our characters. Elton, Scott and Vincent represent the black diaspora. Kobby and Nana represent two opposing Ghanaian native identities. Kobby represents a western leaning Ghana, whereas Nana represents Ghanaian traditional society and the Ashanti ethnic group. These two aspects of Ghanaian identity are presented through the characters as being at odds with one another. Their relationship is fraught with tension, as they both consider the other to negatively reflect Ghana. Despite their differences, they both view Elton, Scott and Vincent’s behaviour and approach to being in Africa for the first time both humorous and frustrating. Elton, Scott and Vincent each in their own way criticise Kobby and Nana for the way they choose to engage with their ancestral history. Kobby shares how he feels about generational trauma;

‘My Dad doesn’t understand that I’ve always been a little empathetic sponge, soaking up the trauma wherever I find it, and generational trauma is something I fear I won’t be able to wring out. Pain that doesn’t die away, pain that won't cross over. That scares me. Still, he holds this trip over me as if it were a right of passage. His dad went; in fact, far more dads than he will ever imagine, a lineage of men witnessing history, or playing a part in it went.’

This theme of tension also comes up surrounding the gay experience and how the local queer do, or don’t, survive in Ghana. The story explores the complexity between the identity of being a black gay man. Whilst the story contains incredible exploration about cultural appropriation and the lasting effects of imperialism, my favourite part of the whole book were the narrations from ‘The Enslaved’ at the bottom of the sea. I thought the way Ben Ben included them as part of the narrative was exceptionally well done and held some of the best prose throughout the whole book. Here’s a taste;

‘We are the voices in your head. The voices of the dead. The brothers who never left. The brothers who were thrown overboard. Welcome.

This was our last home on land, living on borrowed time, on shackled time that still stretched, and stretched, until space became smell became hell, before we were taken to the sea. Take off your shoes and step into our footprints that have mangled the floors, shifted its form until the bottom has worn so thin you can feel the fires of hell underneath. There is no ground in this dungeon that is not an imprint of a thousand overlapping foot-prints’

Despite loving the exploration of the themes of colonial violence, sexuality and transnationalism, as well as deeply admiring some of the prose, I did struggle with parts of the book. The pacing at times felt disjointed and chaotic. This resulted in me frequently not understanding what I had just read or how certain passages fitted into the wider narrative. I can understand how Ben Ben’s writing style was intentionally chaotic to catch the reader off guard, but often I found the stream of consciousness passages to take away from the intense social critique of the narrative. I’m still not quite sure what happened at the end and I feel ultimately a bit dissatisfied that I struggled to understand it. It’s a book where I would love to speak to Ben Ben himself about how he perceives the ending. I finished it with even more questions and perhaps that is what he intended.

‘No One Dies Yet’ is in many ways groundbreaking. However, because I found it hard to follow at times I couldn’t call this a buy. I loved the dark humour, the themes it explores and the conversation it is having about black diaspora. But for the chaotic style, structure and highly ambiguous ending, I would not overly recommend it. I enjoy ambiguous endings, but this one hinges on an ambiguity which undermines the entire book. But perhaps some people would enjoy this type of deceit from a narrator. I would call ‘No One Dies Yet’ a borrow. If anyone has read this or does anytime soon please let me know so we can talk about it. Frankly I am desperate to be able to discuss the book with someone who knows the plot. I am so curious as to how other people may have interpreted it.

‘The Details’ by Ia Genberg is a story about connections and relationships. The story is made up of four parts as our protagonist writes four letters to people who have shaped her throughout her life while she is in the throes of a fever. She writes to an ex-girlfriend, a forgotten friend, an old lover who leaves something unexpected behind and a woman who is consumed by her own anxiety. A thousand little memories from across her lifetime are laid bare in vivid detail. It is a novel built around four portraits and the small details that, pieced together, comprise a life. It raises profound questions about the nature of relationships and how we tell our stories. The result is an illuminating study of what it means to be human.

After several borrows in a row, I was really wanting to end the month on a book I loved. And I’m so glad I chose ‘The Details’, because I absolutely loved it. It was such an incredibly emotionally nuanced and beautifully written book. It is a tender and moving exploration of the relationships that shape our lives, those of old lovers and friends, parents and children, as life is but a collection of the people we surround ourselves with.

‘We live so many lives within our lives - smaller lives with people who come and go, friends who disappear, children who grow up - and I never know which of these lives is meant to serve as the frame. [...] No ‘beginning’ and no ‘end’, no chronology, only each and every moment and what transpires therein.’

The synopsis asks ‘Who is the real subject of a portrait, the person being painted or the one holding the brush?’. And that is the key question here, because while the book paints the portrait of four different people, the real story being told is that of our narrator, who she is, her hopes and dreams and what she values. It illuminates the fact that any one person’s story is merely an amalgamation of the people who’ve shaped their lives. Of how we can’t interact with each other unscathed, we carry parts of one another everywhere we go. This is incredibly skilled writing from Genberg, to be able to paint such a detailed picture of our protagonist without ever directly describing her. ‘The Details’ is an extremely mesmerising exploration of human relationships and the power of memory. It offers an alternative look at when people leave our lives, it doesn’t always need to be negative. Rather, it can be seen as changing and enriching our existence in a myriad of different ways. We cannot see it in the moment, but with time we can come to understand that we are all made up of those we’ve spent time with, whether we like it or not.

Despite the four portraits being brief, as a reader I felt like I’d been a part of each of their stories for years. Which is a testament to the gentle and skilful way Genberg writes. This story is all about the beauty in what we think is just the mundanity of our lives. The closing line of the book made me shed a tear;

‘Soon it will be too late. And that’s why we have to exert ourselves to the utmost’.

I love literary writing about friendships and relationships, so I felt like this book was made for me. I loved it so much. I unequivocally recommend it and would call it a buy. I think any lovers of Sally Rooney or Rachel Cusk would really enjoy this. (Thank you Fiona for this book - you know me very well.)

And that concludes my January Reads! My favourite books of the month were ‘How to Say Babylon’ and ‘The Details’.

My first read of February is ‘Cocoon’ by Zhang Yueran. Translated from Chinese it tells the story of a new generation coming to terms with China’s past and the Cultural Revolution. Two childhood friends reunite and are both determined to know more about their grandparents' generation. Yueran is hailed to be a unique and fresh voice representing a new generation of young writers from China. So far it has been wonderful - the writing is really incredible.

Let me know your thoughts:

What did you read and enjoy in January?

Have you read any of these books? If so, what did you think of them?

Which book are you most interested in reading from this post?

Before I go, has anyone read Poor Things by Alasdair Gray? I saw the film at the weekend and loved it (with some minor gripes) and now I really want to read the book. If anyone has read it please let me know what you thought of it! Equally, if you want to chat about the film I am ALL ears for your thoughts and feelings in the comments.

Thank you so much for reading this newsletter. See you next month!

Happy Reading! Love Martha

Thank you for reading Martha’s Monthly.

If you know someone who is always looking for books to read, forward them this newsletter and share with a friend!

And if you’re feeling generous, hit the little heart at the top or bottom of this email to let me you enjoyed it <3

Catch up my last two posts here:

Did you enjoy this post and the types of books I discuss? Subscribe! and never miss an opportunity to discover new and interesting books to read.

It is scientifically proven that reading translated books makes you cooler.

‘Madiga’ is a group of castes, comprising untouchable agricultural labourers, leather workers; in these stories also musicians, dancers and performers.

‘Jogini’ is a child or woman married off to God. Once this is done, she cannot marry anyone else and is forced to lead the rest of her life as a sex slave to the village. It is a practice limited to Dalit and lower caste communities.

Juneteenth is a federal holiday in the United States commemorating the end of slavery

https://alonghouse.com/the-year-of-reckoning-a-return-to-___/- almost all of this paragraph is directly quoted and paraphrased from this piece.

I get so triggered by religious parents!!!! Just reading the synopsis of How to Say Babylon makes me want to slap somebody, but you also make it sound SO good. Maybe I should give it a shot... I'm super late to comment so you already know what I've been reading :)

I’ve added three of the titles to my Library List. Thank you for such thorough, detailed and well researched reviews. I’ve just subscribed 😊