Welcome to Martha’s Monthly, March Reads edition! Although I am not able to have an accidental theme like last month (which truly was an accident), I did keep an eye out for one in March, because who doesn’t enjoy cohesiveness? And I found one! (clearly I’m going to be doing this every month from now on).

Several of the books I read this month had strong themes of identity, what it means to be human and exist within the world we have constructed. Existentialism was a prevalent theme this month, with multiple books questioning our relationship with work, free will, purpose and how we define identity.

To see the translated reads from March on Martha’s Map, including authors from Brazil, Italy, Japan and France, click here.

For those who are new, buy, borrow, bust is my recommendation key. Buy = I immensely enjoyed and heavily recommend this book. Borrow = I think this book is still well worth a read and I’m glad I read it. Bust = I wouldn’t recommend this book from my own reading experience.

Let’s get into it.

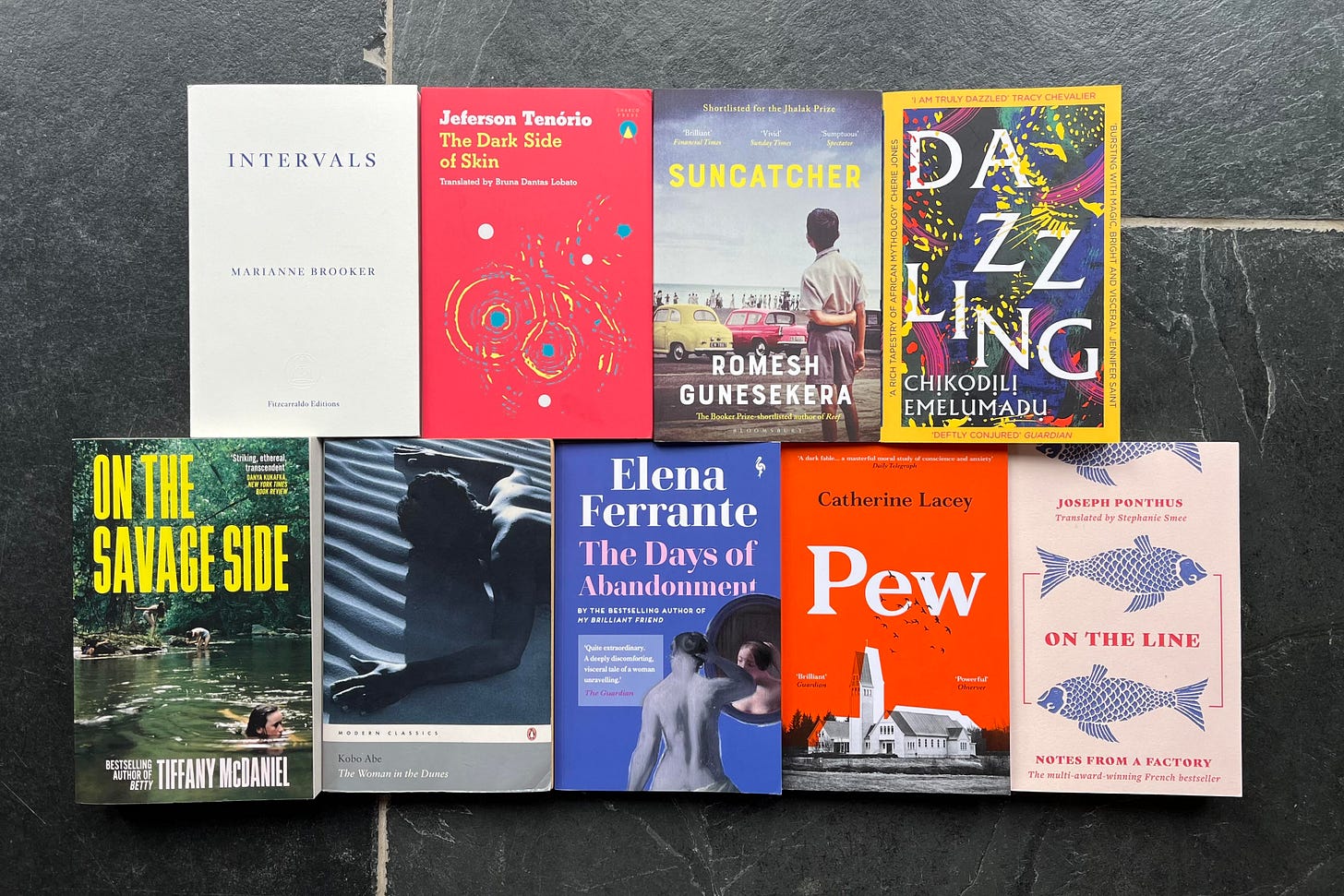

‘Suncatcher’ by Romesh Gunesekera is a tale of the complexities of growing up amid social and political change. In 1964 the country of Ceylon is on the brink of change, but our protagonist Kairo is at a loose end. School is closed and the government is in disarray. All Kairo wants to do is hide in his room or escape on his bicycle and daydream. But then he meets the magnetic Jay and his whole world is turned upside down. The adults in Jay’s life have no say in what he does or where he goes. He keeps fish and traps birds for an aviary he is building in the garden of his grand home. Jay’s ostentatious home holds his mentally unwell and eccentric mother and a father fuelled by anger. Jay guides Kairo from the realm of make believe into one of hunting, guns and fast cars alongside his suave Uncle Elvin. Through their friendship, Kairo begins to understand the price of privilege and embarks on a journey of devastating consequences.

In 1964 Ceylon was less than a decade away from becoming ‘Sri Lanka’.1 ‘Suncatcher’ is a coming of age novel about boyhood and friendship, contrasting dramatically against what was happening in Ceylon at the time. It contains a series of metaphors of the dangers waiting in the adult world for Kairo and Jay as they grow up surrounded by turmoil. This socio-political turmoil is in the background of the novel, as the focus is on Kairo and Jay’s friendship. While the adults around them are presented to be deeply struggling in a variety of ways with the destabilising social change, Kairo and Jay are presented to not quite understand the complexities of what is going on, but sense change is coming. Jay’s parents were involved in British colonial rule as they own a plantation and Kairo is shown to feel increasingly uncomfortable with their beliefs and attitudes towards certain ethnic groups.

The writing is incredibly stylised, arguably to its detriment, but there was a literary nod that I did enjoy. It became incredibly clear while reading that ‘Jay’ is based on Jay Gatsby from ‘The Great Gatsby’ by F Scott Fitzgerald (only one of the greatest books of all time); and Kairo is our Nick Caraway. Everything in Jay’s life glitters; he owns exotic birds, lives on an estate, has a chef, cars, and glamorous parents who hate each other. Kairo is initially in awe of Jay’s charm, charisma and lavish lifestyle. But the more time he spends with Jay the more disillusioned he becomes with the world of the colonial past Jay represents. This literary parallel adds a sense of foreboding, as we know something terrible is going to happen.

Ultimately I found the story hard to connect with. The writing was stylised in a way that, I think, detrimentally impacted the character development and study of Kairo and Jay. I understand the lavish descriptions of the landscape were intended to convey the beauty of Sri Lanka, but I think this took away from the plot of the story. The relationship between the boys is endearing but beyond that ‘Suncatcher’ felt uninteresting and tedious to read as I was not engaged by the way the story developed. I thought the structure fundamentally did not compliment the story, with only seven dense chapters across 300 pages. This drawn out pacing with overly flowery prose resulted in a storyline that became a real challenge to follow. I wouldn’t recommend ‘Suncatcher’, so I would have to call this read a bust. I felt quite devastated by this being a bust and it put me in a reading slump for almost a week!

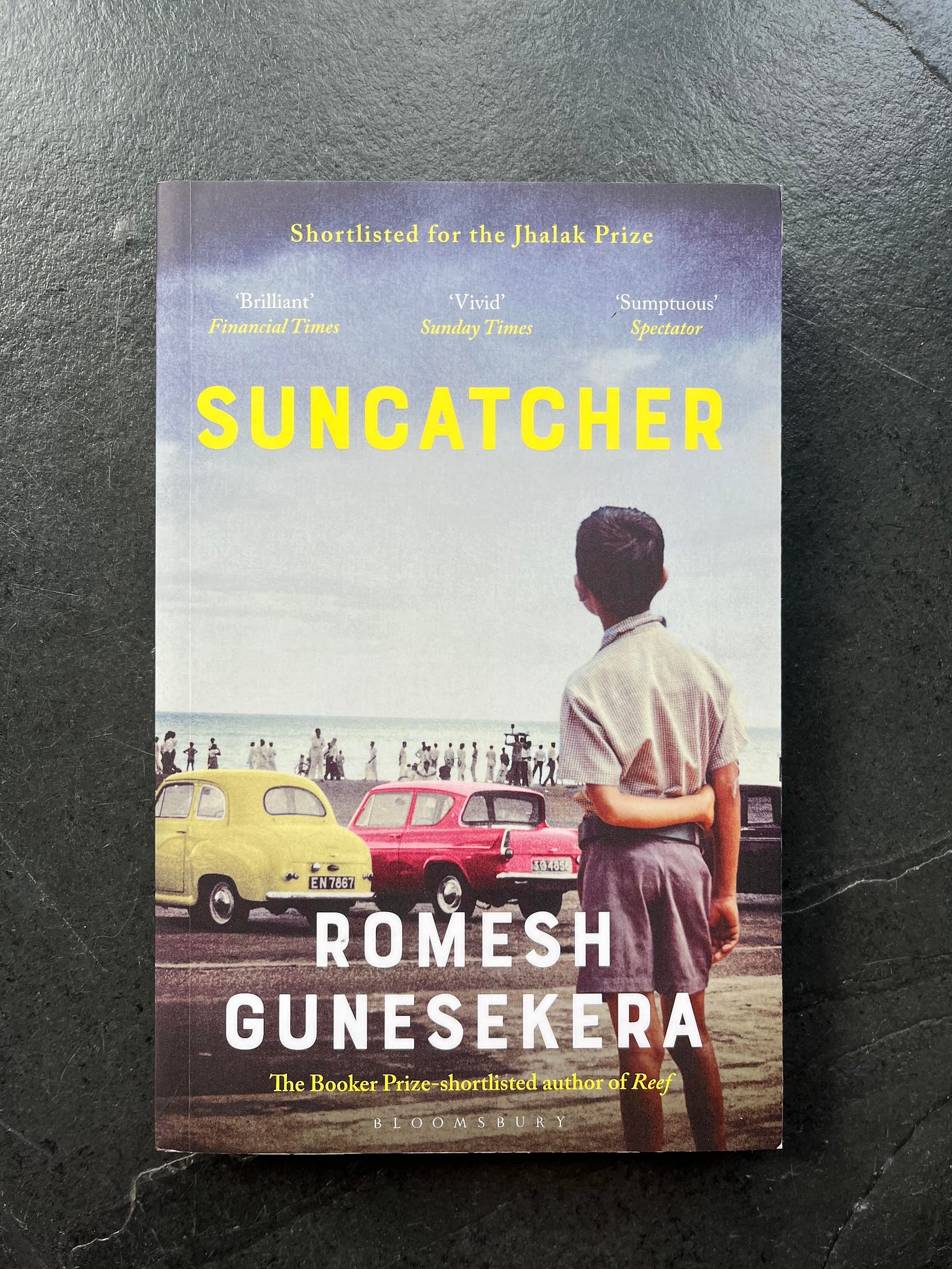

‘The Dark Side of Skin’ by Jeferson Tenório. Life under Brazil’s ‘cordial racism’ comes painfully alive in this novel of fathers and sons. Pedro’s father has been murdered, and by going through the objects he left behind, Pedro is searching for meaning and identity amongst an archeology of affections. He is investigating and retracing his family’s trajectory through the streets of Porto Alegre and the morass of Brazil’s pervasive racism, violence and bankrupt institutions. ‘The Dark Side of Skin’ explores the inescapable bonds and burdens of family in a beautiful and painful account of loved ones lost and found.

‘The Dark Side of Skin’ was absolutely sensational. The story seeks to understand the complexities of growing up as a person of colour in a society with a history of police brutality and systematic racism. Tenório sinks us into a generational story of Pedro’s parents; Henrique and Martha. By establishing the experiences of Henrique and Martha’s past, we gain an understanding of how they have been victims of extensive racism but struggled to identify and understand that this is the case. From Henrique’s childhood to his murder we are taken into his psyche. We learn that Henrique grew up surrounded by violence and he experiences extensive racism from girlfriends and the police before he even understands what is going on. Since racism is so much a part of the social fabric, Henrique lives most of his adolescent life unaware that he is experiencing oppression. We see how intrinsic racism is within the fabric of Brazilian society as we are introduced to white individuals constantly saying to Henrique that they mistrust black people and think they are criminals. We see the first time Henrique experiences ‘direct’ racism in a job interview;

‘I don’t like black people. [..] I don’t like them because a couple of black people who worked at my house in Garibaldi as caretakers stole from me. [...] Since then, I’ve stopped trusting black people. Until that moment, you’d never suffered any racism, at least never so blatantly as this, not that you remember. [...] You didn’t even know what it meant to be black yet. You hadn’t talked to anyone about racism, about Blackness.’ - p.10 in ‘The Dark Side of Skin’

Throughout the story the racism simmers under the surface. As Henrique grows up and starts to gain an understanding of what is happening, the racism moves from the peripheral of the story to the centre stage. Racism pervades his life more as he grows up, and this is not because it is ‘happening’ more to him, but rather Henrique has gained more awareness of the racism he is experiencing in Brazilian society. This gradual change of focus powerfully accounts for what it is like growing up as a person of colour in a society that is so cordially racist. That as a child you are unaware of the prejudice but as soon as you gain understanding of systematic, institutionalised and casual racism you can’t unsee it; because it's everywhere.

Tenório powerfully writes in second person which is a challenging perspective to write from, but it is exceptionally done. The writing is so emotionally charged and compelling. The characterisation of racism in Brazilian society is horrifying and as a reader I felt so moved by the style of writing, constantly being addressed as ‘you’.

The prose throughout the book is an absolutely beautiful exploration of a father figure and a human being who is flawed in ways we all recognise; a man who is trying his best, in a world where he is criminalised, discriminated against and misunderstood. The book is full of so much hate and violence as well as tenderness and resilience. The discussion around what it is like to be black in Brazil was so candid and yet incredibly urgent. The Translator's Note highlights just how pressing the racism is in Brazil; ‘Black people in Brazil are disproportionately killed by police: in 2020, the year the book was originally published, 78% of the people murdered by police in Brazil were black’.2

‘But they’ll never know anything about what you had besides your skin. They’ll never know who you were besides a threat.’ - p190 in ‘The Dark Side of Skin’

I loved every minute of reading this book and I already know it's going to be a favourite from the year. It was deeply moving. The way Tenório portrays police violence against black people in Brazil was frightening and painful to read. Despite the weight of the themes within the story it was exceptionally easy to engage with, and reading about Henriques story was as joyful as it was painful. I absolutely recommend this book, it was a completely transformative reading experience. ‘The Dark Side of Skin’ is a complete buy.

‘On The Savage Side’ by Tiffany McDaniel. Inspired by the unsolved murders of the Chillicothe Six, this is the story of twin sisters Arcade and Daffodil. With their fiery red hair and a thirst for escape, they have an unbreakable bond. Together they disappear into their imagination and forge worlds far beyond their own. But no matter how hard they try, Arc and Daffy cannot escape the generational ghosts that haunt their family and are left to fend for themselves in the shadow of their rural Ohio town. Years later as the sisters wrestle with the memories of their early life, a local woman is discovered dead in the river. Soon, more bodies are left floating in the water and the sisters must cling even tighter to each other as it becomes more difficult to survive.

‘On The Savage Side’ is a poignant story about the bond between sisters and the search for justice in the face of tragedy. I picked up this book because I really wanted an engrossing and devastating story to get completely invested in. Exploring the experience of growing up among addicts, similar to the emotions found in ‘Shuggie Bain’ and ‘Demon Copperhead’, this story skilfully evokes each aspect of the girl’s humanity and defiance in the face of generational evil. The twins are being brought up in a home of drug addiction where they experience extensive levels of abuse.

The prose is colourful with the hope and imagination of the twins as it becomes clear this is where they can make themselves feel safe. The reality of addiction is juxtaposed with vivid imagination and a juvenile outlook and perspective of the world. McDaniel creates a literary world where fairies and violence both dominate the page, artfully humanising the women with their imaginations, instead of reducing them to victims of the cruel and suffocating realities of poverty and drug abuse. This colourfully rich prose packed with hope and imagination simultaneously reflects the innocence of the girls, the reliance on their imagination to remove them from their reality and the high of the addicts around them; no one is present in the real world.

McDaniel empathetically explores what it's like to be a woman within these cycles of abuse and the awareness the women have in recognising what is going on around them.

‘A witch is not a pointy hat or a broom or warts. A witch is merely a woman who is punished for being wiser than a man. That’s why they burned her. They tried to burn away her power because a woman who says more than she’s supposed to say, and does more than she’s supposed to do, is a woman they’ll try to silence and destroy’ - p.45 in ‘On The Savage Side’

It feels equally disconcerting and fitting to have the innocence of imagination and harrowing effects of drug addiction and severe poverty come together on the page. ‘On The Savage Side’ is a devastating story about those who are often forgotten about and left behind within a society that should be protecting them. McDaniel constructs a deeply evocative and devastating story of the bonds of family and community, and how those bonds can fail us. The character development of Arc and Daffy was done exceptionally and I felt completely enthralled by their striking resilience in the face of such extensive abuse and suffering. The story is full of fierce love between women and I thought the approach McDaniel took towards writing about something so devastating and sensitive was very well done. She balanced the light and dark flawlessly. I enjoyed reading this book and would recommend it! I’d call it a buy. I have always wanted to read ‘Betty’ by McDaniels and now I want to even more.

‘On The Line: Notes from a Factory’ by Joseph Ponthus. Unable to find work in his field, Joseph Ponthus starts to pick up casual shifts in the fish processing plants and abattoirs of Brittany, France. Day after day he records the nature of work on the production line; the noise, the exhausting rituals and the physical suffering. But as he works, he finds solace in a life previously lived - the woman he loves, the happiness of a Sunday, his dog and the smell of the sea. This novel is written in verse and is a poet’s ode to manual labour, and to the human spirit that makes it bearable.

‘On The Line: Notes from a Factory’ is a mediation about the emotional and personal experiences of working class individuals in labour-intensive factory jobs, particularly in the unique setting of an abattoir. Ponthus is a poet so this novel is set up like verses of a poem. Structurally and lyrically this was so refreshing to read. With each new phrase, Ponthus ‘returns’ to a new line, as he returns to the factory, producing a rhythm that matches the relentlessness of the production line.3 This approach to writing creates visual space on the page which allows us to reflect and deeply consider what it means to be human, to have to work and to have to suffer.

This book was deeply thought provoking and made me consider capitalism, food production and the disconnect we have from our food. ‘On The Line’ explores the dehumanisation and unrelenting industrialisation of food production; from the animals slaughtered to the people working in the factory and those who consume the product at the end. Ponthus explores the soul altering deadening effect on oneself and the animals who suffer.4

It was inherently philosophical, exploring the need to work and to live, but how a job can consume you so you are only living to work. Ponthus explores; what is the meaning of life under capitalism? The proletarian novel asks where do we go from here? Ponthus is juxtaposing the state of the modern world; being an educated writer discussing some of the greatest French writers while in the next verse, hosing down an abattoir covered in animal remains. What keeps Ponthus sane, what sparks joy amongst the slaughter, is beauty. The beauty of his girlfriend, his dog, the sunshine and the water, which are all things you do not have to work for and not controlled by capitalism.

This raw and tender testimony on life in the factory had me engrossed and stunned. This book was so conceptually unique and deeply thought provoking. I loved the way ‘On The Line’ made me contemplate life and our relationship with work. I felt it really spoke to such perpetual fears we as people can have about your life passing you by without ever being present;

‘The factory is

Above all else

A relationship with time

Time that passes

That doesn’t pass’ - p129-130 in ‘On The Line’

The poetry investigates the concept of working to ‘get by’, and before you know it years have passed and you’re still working in the same place. It compassionately explores themes of never enough time, never the right time, never a ‘real’ job; asking what is real, right and enough within the world we’ve constructed? It is a compelling portrait on labour, consumption and identity by capturing the mundane, beautiful and strange aspects of human existence. The camaraderie felt by Ponthus while working with others speaks to a larger feeling across the world that human relationships can truly be that universal thread that helps you make it through the week. The prose is packed with elegance and humour that sit in poignant contrast to the blood and sweat of the factory floor. I loved reading this so much and would without a doubt recommend it and call it a buy.

‘Dazzling’ by Chikodili Emelumadu explores the magical and mysterious aspects of African folklore through a dual narrative of two characters; Treasure and Ozoemena. Treasure and her mother lost everything when Treasure’s daddy died. Haggling for scraps in the market, Treasure meets a spirit who promises to bring her father back - but she has to do something for him first. Ozoemena is suddenly forced into a different world of spirits as she becomes aware of her patrilineral destiny to defend her people by becoming a leopard (stay with me). Her father impressed upon her what an honour this was before he vanished, but it’s one she couldn’t want less. As the two girls reckon with their burgeoning wildness and the legacy of their fathers decisions, Ozoemena’s fellow students at her new boarding school start to vanish. Treasure and Ozoemena will face terrible choices as each must ask; what must they sacrifice to get what's theirs?

I don’t read much fantasy but after reading such a philosophical book which made me think (maybe too much) about our relationship with capitalism, I thought it was necessary to read a story about spirits and shape-shifting. At its core ‘Dazzling’ is a dense tale of good and evil; tradition and girlhood. The folklore explored in this story is based on Igbo religion and culture which believes that spirits and ancestors protect their living descendants. In Igbo mythology spirits are neither benevolent or malevolent; instead they are believed to possess both positive and negative attributes. This belief in dual nature is to help maintain a respectful and harmonious relationship with the spiritual world.5

Treasure and Ozoemena both have relationships with the spiritual world and contrastingly use this access for better and for worse. The girls are attempting to navigate the otherworldly spheres of female adolescence and Nigeria's spiritual offerings all at once, which is unsurprisingly overwhelming. Ozoemena’s setting within the boarding school was my favourite aspect of the story. Ozoemena’s characterisation was very well done, and despite Treasure being the objective villain in the story, it was hard to dislike her because of how well Emelumadu explored her duality and humanised her.

Standing alone both these storylines were strong and interesting. However, together the storylines didn't always compliment each other as they jumped between past and present in a confounding way. These structural time jumps were initially compelling but it came to its detriment slightly as the story progressed. However, the essence of the story was still very much there and I enjoyed the beautiful prose and characterisation. Shapeshifting and spirits of Nigerian folklore are a colourful and thrilling world to be engulfed in, even if the structure slightly let it down. This story was a zesty and an enjoyable exploration of girlhood coming to head with the world of magic and folk wisdom. I would call ‘Dazzling’ a borrow. It was a nice break from the existentialism. ‘Dazzling’ was Emelumadu’s debut and I am interested to see what she does next.

‘The Woman in the Dunes’ by Kobo Abe was my second classic novel for this year. Translated from Japanese, it is a tale of free will and existentialism. Niki Jumpei, an insect enthusiast, searches the scorching desert for beetles. As night falls, he is forced to seek shelter in an eerie village, half-buried by huge sand dunes. He awakes to the terrifying realisation that the villagers have imprisoned him in a steep-sided sand pit with no means of escape. Tricked into slavery and threatened with starvation if he does not work, Jumpei’s only choice is to shovel the ever-encroaching sand - or face an agonising death.

‘The Woman in the Dunes’ is a contemplative and existential story which explores philosophical questions about the human condition. Through Jumpei’s capture and enslavement to shovelling sand until the end of time, Abe creates a discussion around what it means to be alive and the search for meaning in an arguably meaningless world. Imprisoned, literally and symbolically, by the sand, it permeates every aspect of his life, getting in his food, eyes and mouth. This personification of sand represents times’ ceaseless flow. Mitchell so perfectly analyses how as we read about the man's entrapment in the sand, we are essentially reading about our own. We, too, must spend a lifetime doing meaningless jobs (to the universe at large, not to ourselves) for not much in return.6

Abe was a member of the Japanese communist party and these ideas can be felt deeply through his work. ‘The Woman in the Dunes’ and ‘On The Line’ feel profoundly linked in the existential evaluation of life under capitalism and the discussion of elective imprisonment.

We are given next to no information about the man and woman of the dunes and yet as a reader you feel compelled by them and this is down to the universal relationship we have with work under capitalism. Jumpei’s behaviour towards the woman in the dunes is one of interest - he treats her as a pawn or vessel but never as an individual. Whether this is because she is a woman or because she is deemed to be lacking in a moral compass it is unclear, however she is positioned to not consider the meaning of life outside the one she immediately lives;

‘Why should we worry what happens to others?’ p.223 in ‘The Woman in the Dunes’

The experience of reading ‘The Woman in the Dunes' is one of discomfort. It is uncomfortable to witness Jumpei’s literal experience of being imprisoned and enslaved, along with the internal struggle he faces with his identity and free will. This book is very strange (as you can probably tell) but bursting with metaphors, philosophical discussion and thought provoking concepts on free will.

I really enjoyed this kafkaesque story and I would call ‘The Woman in the Dunes’ a buy! It was interesting and captivating. Although I am only two months into my classic novel goal for the year, I am really enjoying it! It feels so good to be *slightly* resisting the new book release hysteria (which I have found myself more caught up in since starting this newsletter) and to focus on books which have stood the test of time because they are that profound.

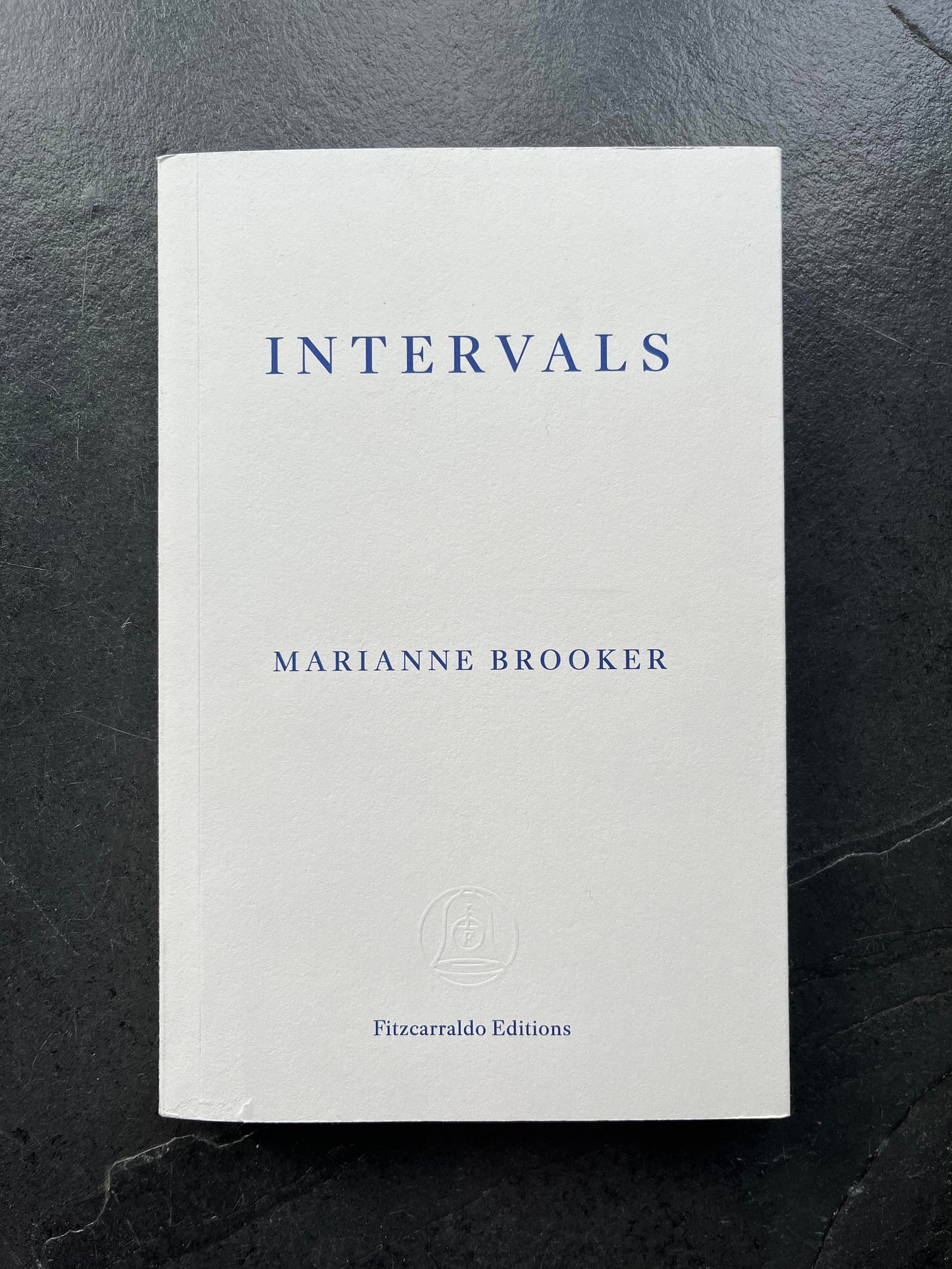

‘Intervals’ by Marianne Brooker is a moving and profound telling of what it means to give and receive care. In 2009 with a harsh wave of austerity on the horizon, Marianne Brooker’s mother was diagnosed with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (MS). After her diagnosis she led a life of combined creativity and activism. But over the period of a decade, her ability to work, move and live without pain diminished drastically. Determined to die in her own home and on her own terms, she stops eating and drinking in 2019. Blending memoir, poletic and feminist philosophy, Brooker reckons with the heartbreak of caring for her mum as she took the decision to die. Brooker raises essential questions about choice and interdependence, and ultimately to imagine a different care system in the UK.

‘Intervals’ explores themes of caregiving, end-of-life decisions and the intersection of personal experience with broader social issues. It is a moving and ultimately devastating discussion around what it means to be disabled and poor within a country that offers terrible care for disabled people and no opportunity to control your death. Even though ‘Intervals’ is UK focused, I think it speaks universally to the relationship between disability and care costs. The UK Government is currently facing the UN for its extensive violation of disability rights.7 The government actually refused to attend a meeting to review its treatment of disabled people back in 2023.8 Brooker speaks to all of these issues, and more, that her mother was facing with the progression of her MS. She asks what makes a good death? And what does it mean to take the decision to die when your life is so absent of a future.

I think Brooker is entitled to a huge amount of rage surrounding what happened to her mother, however the measured clarity she brings to the page within her writing about a subject so deeply personal is very impressive. She writes about the complexity of caring for a family member and the weight this bears to those doing the caring. The love that Brooker has for her mum is deeply felt on the page as she allows us to catch a glimpse of the emotional turmoil of witnessing someone choosing to end their life. In a country where assisted dying is not possible without prosecution, the only legal way to die is to abstain from food and drink, intrust medical professionals not to interfere and still receive the palliative care that would make death as painless as possible.9 Although this is what her mother in sound mind wanted, Brooker is constantly worried about whether she is doing the right thing.

Brooker’s writing also highlights the sliding scale of care dependent on class, wealth, race and circumstance that are present within the UK in relation to disability and chronic and terminal illness. Brooker’s mother was not a woman of means and this lack of financial agency and ability to fund any private treatment deeply impacted the care she received. The memoir incorporates political commentary about the current government's horrific treatment of disabled people and their plans to force disabled people into the workforce. In 2015 this plan resulted in nearly ninety people dying a month after being declared fit to work, as assessors refused to take evidence from doctors.10 In a blend of memoir and non-fiction about the state of care, ‘Intervals’ is screaming why are disabled people treated like second class citizens and denied the care that they need?

‘Being dead was no great fear of hers, but being compelled to live was killing her’ Brooker, Guardian 202411

This memoir is contrastingly angry and full of love. It was insightful, educational and incredibly interesting to read. ‘Intervals’ is a measured and compelling case for better care, assisted dying and the need for it to give back autonomy to those who have been handed a life of deteriorating pain and unbearable suffering. Although I would have preferred this to predominately be a memoir, and less commentary on politics and austerity, I do think the two are inherently linked and it is a failure to discuss one without the other. Disability and austerity are impossible to separate. I would recommend this book if you’re interested in themes of what it means to be alive, what it means to die, longterm illness and care. ‘Intervals’ is a borrow. It breaches the relationship between illness, death and disability that so many people seem to fear. It’s coming for us all so I think it’s in all of our best interests to understand how we can fund care properly and have access to a dignified death.

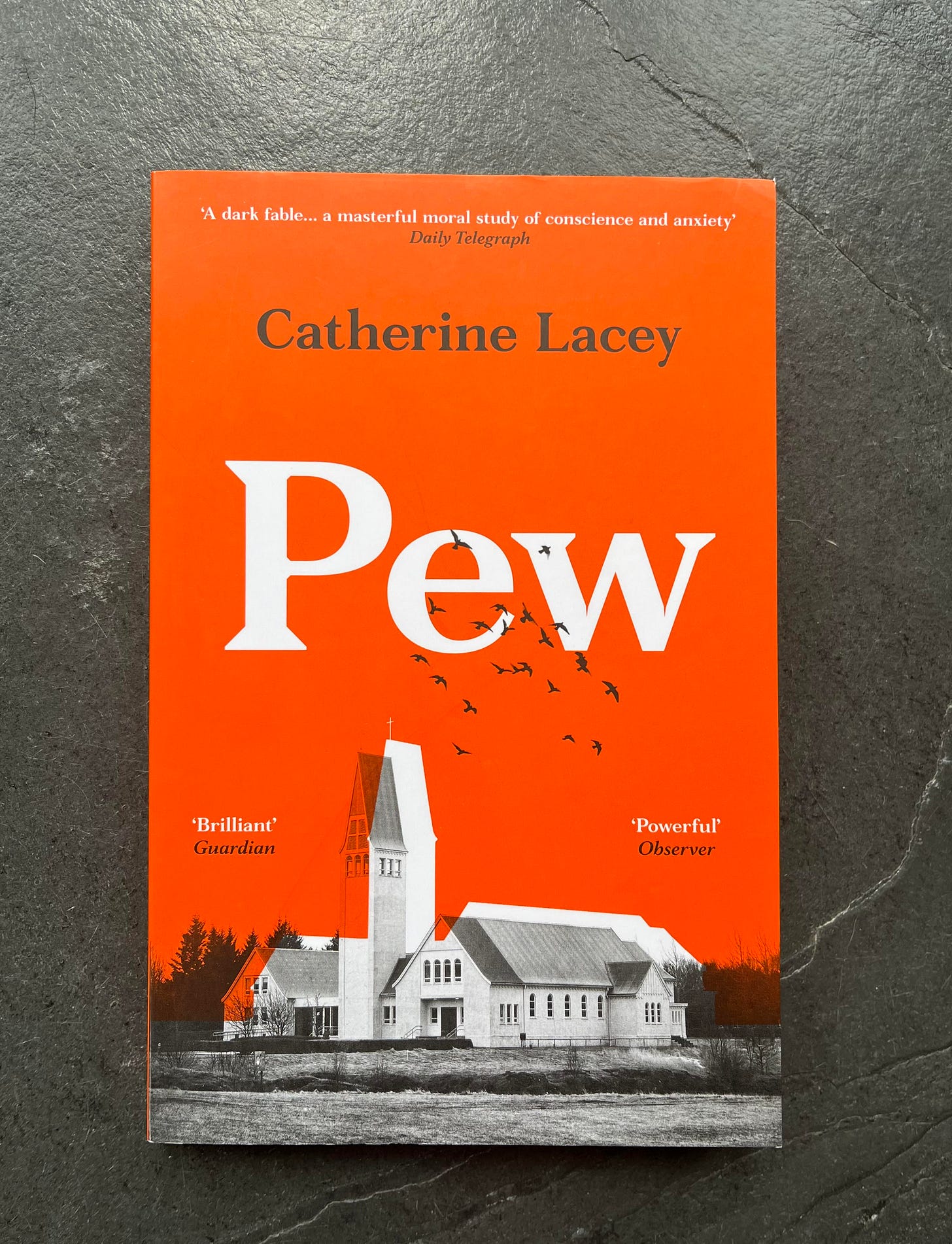

‘Pew’ by Catherine Lacey. One Sunday morning, a mysterious person is found sleeping in the church. The townsfolk call this person ‘Pew’, and seek to uncover who they are; their gender, race, age and intentions. Are they an orphan? And why won’t they speak? Unable to agree on how to treat someone they cannot categorise - whether to adopt or imprison, help or harm them - the community is quickly undone by Pew’s terrifying silence.

‘Pew’ is a novel about the exploration of identity, assumptions and judgement. This was an insanely thought provoking story about how we as humans in society have come to conduct ourselves. How we create purpose, define identity and what happens when we cannot categorise those things. Lacey’s novel is a foreboding fable about the present; our borders, boundaries and fears. The story of ‘Pew’ felt reflective of some of the aspects of identity today that are considered deeply inflammatory; transgender identity, migration, borders, and prejudice. ‘Pew’ explores the concept of how we react to those we cannot identify as a reflection of ourselves. ‘Pew’ feels deeply familiar to read because it is provocative and explores attitudes that we can see permeating and growing across the world. It is eerie why defining a person's body is so important.

The community who find Pew are deeply religious, conservative and incredibly unsettling. The eerie atmosphere reminded me of both ‘Get Out’ and ‘Midsommar’. ‘Pew’ comments on small town religious communities and how they can be insular and bigoted. It explores the relationships that humans can have to religion and subsequently God in order to justify or categorise behaviour. ‘Pew’ examines how religion, identity and being can come to intersect. Lacey cross examines the reaction of this deeply religious community’s inability to accept Pew because they are unable to categorise them in a way they understand. They are able to hide behind this facade of moral and religious superiority because the bible encourages sentiments like ‘love thy neighbour’ but they cannot decide to love if they cannot categorise you. Within this structure of prejudice and strict classification Lacey presents this unravelling of the human psyche, and explores how our psychology reacts when we are confronted with those we cannot define. ‘Pew’ invites discourse around the ideas of what it is that makes us human - is it identity? Or something bigger? Lacey purports that our humanity is not linked to our physical bodies but our minds.

‘The question arose then - did all this human trouble begin in our bodies, these failing things, weaker or stronger, lighter or darker, taller or shorter? Why did they cause so much trouble for us? Why did we use them against one another? Why did we think the content of a body meant anything? Why did we draw our conclusions with our bodies when the body is so inconclusive, so mercurial?’ P.91-92 in ‘Pew’

‘Pew’ feels deeply liminal. It is a complex novel about the question of identity, exploring the notion that the totality of identity is not given but constructed by us. Therefore it is unstable and ultimately non essential. It is deeply thought provoking, asking the reader to consider who we would be if we had to describe ourselves without the categories that humanity relies so heavily on. Without race, gender, age, nationality, job title, religion how would you go about describing yourself? It feeds the notion that our souls and our bodies are not the same and that to react to our most authentic self we have to move past rigid identity markers that are a social construct stifling our true being.

The more we read ‘Pew’, the more we can understand why Pew is choosing to be silent. Every single person views them differently, physically and ideologically, and therefore treats them in accordance with their beliefs. Pew becomes a blank slate where all projections of others manifest; some lash out and are deeply frustrated by their silence while others find comfort and connection. The book is perpetuating the postmodernist idea that the self is created in how we are perceived. The concept of Pew’s character reminded me deeply of Carson McCullers character ‘Singer’ in ‘The Heart is a Lonely Hunter’ who is also mute. Both ‘Singer’ and ‘Pew’ are either feared or adored for their decision not to speak as people are allowed to project their ideas onto them.

I really could write about ‘Pew’ and the way it made me think forever, but I will stop here. I loved this book, it was so strange, poetic and interesting. I would absolutely recommend this book to anyone - we all have to reassess and consider our relationship to identity and how we as human beings subconsciously categorise people. It is a fable about inequality and prejudice. ‘Pew’ is a total buy. I have never considered reaching for ‘Biography of X’ by Lacey before now, but after reading ‘Pew’ I am really interested in her other work. If anyone has read either, or any other work of hers, let me know!

‘The Days of Abandonment’ by Elena Ferrante was the icing on the cake for my month of existentialism and identity crisis books. After being suddenly left by her husband after fifteen years of marriage, Olga’s ‘days of abandonment’ are a desperate, dangerous descent into despair and rage. With two young children to care for, Olga finds it more and more difficult to do the things she used to. Trapped inside the four walls of her apartment in the middle of a summer heatwave, she is forced to confront her ghosts, the potential loss of her identity and the possibility that life may never return to normal again.

This story is a exploration of a woman unravelling. A lucid tale about the emotional challenges of motherhood, marital breakdown and grief. This was my first Ferrante and I was taken aback with the vulgarity and engrossing nature of her writing. ‘The Days of Abandonment’ is the story of a woman indulging in her most selfish and unsettling thoughts, in the face of being left by her husband. In the days after he leaves, Olga goes on a journey of outrageous dishevelment which feels horrifying to read because it juxtaposes almost everything we socially attach and assume to the behaviour of mothers and by extension women - that we must always be vessels of care, no matter the circumstance, and to complain or fail at this is to be defective. 12

Olga (rightly so) teeters on a state of madness as she walks through the grief of her marriage ending, brimming with rage and distress. She grapples with her ageing body, confronted with the disgust that her husband has left her for a younger woman. Speaking to the notion of the madonna whore complex, Olga feels confronted with her role as mother and no longer being sexually desired by the father of her children.13 Reading this spoke to the grief that I think many women feel once they become mothers. Olga feels rage towards her children as their father walks out on them and it is automatically assumed she is the primary caregiver - because of them she is not able to fall completely off the face of the earth despite how much she wants to. ‘The Days of Abandonment’ is a complex exploration of anger in the context of motherhood and grief. Ferrante’s prose turns from horrifying to elating in a matter of seconds as she takes us directly into Olga’s mind as her whole world has been tipped upside down.

The writing was quite extraordinary and I felt deeply unsettled as Ferrante thrusts us into the eye of the storm of Olga’s unravelling. I always enjoy books where we get to experience such unsightly behaviour from women; especially a mother. It is cathartic to witness a mother disrupt the conventions that stereotype motherhood.

In a betrayal so visceral and painful as your husband leaving, Olga is not supposed to struggle, as she should to keep it ‘together’ for her children. However, we all know how unrealistic of an expectation this is and Ferrante speaks to the idea that mothers can be angry and complex individuals whose identity should not hinge on their caregiving abilities or marital status. Not that anything Olga does in this novel should be used as a behaviour guide, but it is memorable to read about a mother who is so furious.

I enjoyed this and would recommend it to anyone who enjoys feeling uncomfortable whilst they read. I’d call ‘The Days of Abandonment’ a borrow, I wish we got a bit more of a story but reading it was a complete fever dream. I am unsure which Ferrante to turn to next! Any suggestions?

And that concludes my March Reads! My favourite reads this month were ‘The Dark Side of Skin’, ‘On The Line’ and ‘Pew’! All of them were sensational. I hope I haven’t put anyone in an existential crisis with the tone of some of these books.

My first read of April is ‘Birnam Wood’ by Eleanor Catton! This bestseller has been on my radar for a while so I am intrigued to see if it lives up to the hype. So for my only thoughts are: it’s long and I fear it might be a predictable trope.

Eyes On The Prize

I am not sure who decided March was THE month for so many literary prize lists to come out but I am overwhelmed. Here are the prize lists that I am following:

☞ The Women’s Prize for Fiction. I am interested in ‘River East River West’ by Aube Rey Lescure, ‘Hangman’ by Maya Binyam, ‘Enter Ghost’ by Isabel Hammad and ‘Brotherless Night’ by V.V Ganeshananthan. Has anyone read any?

☞ The International Booker Prize. I was introduced to two of my favourite books from 2023, ‘Still Born’ and ‘Pyre’ from the prize last year. I have already read ‘Crooked Plow’, ‘The Details’ and ‘Not A River’ from the current longlist. I am going to read the shortlist for this prize!! Stay tuned for my thoughts which I will share before the winner is announced (on the 21st May).

☞ Jhalak Prize is for BAME British writers. It is nice to see ‘Small Worlds’ by Caleb Azumah Nelson and ‘Fire Rush’ by Jacqueline Crooks on there. I am interested in ‘A Flat Pace’ by Noreen Masud and ‘A Pebble In The Throat’ by Aasmah Mir - has anyone read?

Let me know your thoughts:

❀ What have you read and enjoyed in March?

✮ Have you read any of these books? What did you think?

✿ Do you have any more classic novel suggestions for my reading goal this year?

❊ And has anyone ever read an entire literary prize list?! Or at least tried?

Thank you, as always, for reading. I hope you found a book you might like to read!

See you next month,

Happy Reading! Love Martha x

If you know someone who is always reading, share this newsletter with them!

Catch up on what you might have missed:

And before you go - if you enjoyed this, why not subscribe? <3

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dominion_of_Ceylon#Problems

Translators Note, p.201 in ‘The Dark Side of Skin’

‘With each new phrase, Ponthus ‘returns’ to a new line, as he returns to the factory, producing a rhythm that matches the relentlessness of the production line.’ is a quote from Stephaine Smee in the translator's note in book

The quote ‘Ponthus discusses the soul altering deadening effect on oneself and the animals who suffer.’ is a line paraphrased from this article - https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/on-the-line-joseph-ponthus-book-review-hilary-davies/

https://www.oriire.com/article/the-role-of-spirits-and-ancestral-spirits-in-igbo-mythology-guardians-of-tradition-and-identity#:~:text=The%20belief%20in%20spirits%20and%20ancestral%20spirits%20is%20an%20integral,own%20unique%20attributes%20and%20purposes

Mitchell in ‘Introduction’ from ‘The Woman in The Dunes’ p.xii

https://bylinetimes.com/2024/03/11/united-nations-summons-uk-government-over-breaches-of-un-convention-on-disabled-peoples-rights/#:~:text=A%20report%20into%20the%20breaches,adequate%20living%20standards%20and%20social

https://www.disabilityrightsuk.org/news/uk-government-refuses-attend-un-meeting-scrutinising-its-rights-violations-disabled-people

Sometimes referred to as VSED ‘voluntary stop eating and drinking’

Statistic is from page 16 in ‘Intervals’ by Brooker and is also discussed in this article -https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/nov/23/jeremy-hunt-benefit-sanctions-tory-cruelty-autumn-statement

Quote from this article: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/feb/04/intervals-marianne-brooker-multiple-sclerosis-ms-extract

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madonna%E2%80%93whore_complex

I currently travel full time, and I try to read literature in translation that's from each country I'm in while I'm in it. Based on your recs, I've read Not a River and A Little Luck while in Argentina and loved both!

On a similar note: I did read Days of Abandonment on a sweltering hot rooftop in Naples and it really added to the experience. I have to recommend diving into the Neapolitan novels - they are her greatest works and stand up to all the praise, especially if you like a sprawling multi decade novel, a la Tree Grows in Brooklyn or The Poisonwood Bible.

I too am trying to read way fewer buzzy new books this year - I did a personal audit of my reading from 2023, and had about 15 books I read that were so "meh" because I got caught up in the hype. I'm tracking way better this year already, but I did succumb and read Kaveh Akbar's Martyr! and Madeleine Grey's Green Dot, and thankfully lucked into two 5 star bangers.

Last thought: I am so thrilled by your review for Pew, and it's now bumped to the top of my list. Biography of X was one of my last reads for 2023 and just absolutely blew me away. An astoundingly creative and complexly pieced together book. 10/10, and I hope you love it.

I was especially interested in your thoughts on Ferrante - I read My Brilliant Friend and didn't connect with it, which made me wonder what was wrong with me since it was so beloved. SO MANY PRIZES! I wanted to read a bunch of Booker's this year but the first one I started with wasn't my favorite so I can't say I am motivated to read any prize nominee indiscriminately any longer. Cheers to any one who tries though!