Welcome to ‘Martha’s Monthly’, February Reads edition! Identifying a theme for this month was hard, as these books were strikingly different. Yet, in a very broad sense, the perspective that kept recurring was one of confinement.

They all have protagonists who are, or feel, trapped; whether by aspects of their existence like their gender, race, sexuality. Or, in a more literal sense, because of illness, conflict or geography. They interrogate the experiences of those who are, in a variety of ways, stuck.

To see the translated reads from February on Martha’s Map, including authors from Argentina, Croatia and Cyprus, click here.

For those who are new, buy, borrow, bust is my recommendation key: Buy = I loved this book and highly recommend it. Borrow = I liked this book and think it is worth a read. Bust = I wouldn’t recommend this book from my reading experience.

‘Brotherless Night’ by V.V. Ganeshananthan

‘I recently sent a letter to a terrorist I used to know […] I used to be what you would call a terrorist myself [...] We were civilians first. You must understand; that word, terrorist, is too simple for the history we have lived.’ These are the first lines in Brotherless Night, an immediate confrontation of the history and the humanity that is contained within this book. From the outset, Ganeshananthan provocatively asks the reader to consider our language to violence and the role the word ‘terrorist’ plays in our perspective of conflict.

Brotherless Night follows a family fractured in the early decades of the Sri Lankan Civil War. Our protagonist, Sashi, and her four brothers, live in Jaffna with her parents. Their family dynamic is idyllic and the kids are ambitious and earnest. Sashi wants to become a doctor, but her family life and dreams for her future crumble in July 1983, when anti-Tamil rioting broke out across the country, killing over 5,500 Tamils. Sashi and her family are Tamil and are forced to witness this violence tear through their lives. Sashi’s brothers and their friend, K, get caught up in political ideologies and mounting violence. Desperate to act, Sashi accepts an offer to work as a medic at the field hospital for the militant Tamil Tigers. However, as Jaffina increasingly turns into a war zone, and Sashi witnesses certain decisions made by the Tigers, she becomes increasingly fraught about where she stands and who she can trust.

This novel is relentlessly gut-wrenching. It meticulously recounts some of the horrendous violence that occurred in the conflict, specifically against women. Ganeshananthan explores the myriad of ways war fractures our humanity through the enormous spectrum of grief suffered by Sashi’s family. It is challenging to describe conflict without flattening it, yet Ganeshananthan manages to weave together this brutality with aching moral complexity. She approaches the topic with an exceptional dichotomy of sensitivity and anger, and never sensationalises it. It is remarkable to read.

‘It did not occur to me to count or prove, to measure our losses for history or for other people to understand or believe. I did not collect evidence of my own destroyed life; I did not know people would ask me for it’ p.74 in Brotherless Night

Sashi has a complex relationship to the conflict, and because of her brothers, she is in the eye of this storm. She has multifaceted motivations for getting involved in the Tigers and subsequently embarking on the incredibly dangerous project of documenting the human rights violations that are taking place. Many boys she loves are involved in the Tigers, and this complexity is never lost throughout the novel. Sashi desperately seeks a guiding light of what is the right thing to do, and is consistently devastated that such a guide does not exist when it comes to war. This claustrophobia, within the conflict and in her own heart, is present on every single page. She urgently seeks a way to fight for the rights of Tamils while not wanting anyone to get hurt. Sashi’s narration felt like a plea to humanity; a testimony of how wrong it can go.

There is also a frustration present in Sashi, with the conflict, but also as the explainer. The prose often slips into second person, addressing the reader as ‘you’. In these addresses, the reader is forced to reckon with whether they are part of this narrative, the one which asks Tamils to collect the evidence of their destroyed life, to prove and explain their pain.

Brotherless Night reads like a witness testimony for women and the experiences they endure during conflict. Ganeshananthan addresses how sexual violence is used to coerce civilian women, yet these narratives are so often left out from discussion. There is a thrust throughout the novel that civilian women, in any conflict, are the ones experiencing the front of the violence. Gandhi famously said women are ‘strong in suffering’ and proclaimed women are designed to endure. Sashi wants to resist this gendered assumption of pain, to contradict and to be weak in her suffering.

Ganeshananthan brings these stories about women in conflict to life, directly addressing experiences that are often associated with so much shame. Brotherless Night is about the many men that have lost their lives, but it is more powerfully about the women that lost theirs in a different way. Loss of life in the Sri Lankan Civil War is often discussed in the disappearance of men and young boys, many who were forced to join the Tigers. However, it is rarely discussed in relation to women, and Ganeshananthan brings their experiences to life. Conflict is inherently contentious and Ganeshananthan recognises this. Fiction is a landscape to explore the human consciousness and the moral ambiguity of our world that is hard to achieve elsewhere, and Brotherless Night encapsulates this.

I loved this book, in all that it allowed me to learn and feel. Reportedly it took Ganeshananthan over twenty years to write this and that makes me even more impressed. The level of research that is contained within this novel is astounding. I would unequivocally recommend this and call it a buy! It encompassed so much about Sri Lanka as a country, identity and home. The story is messy, one that does not end ‘neatly’, making it unfailingly human in all its moral and emotional complexity.

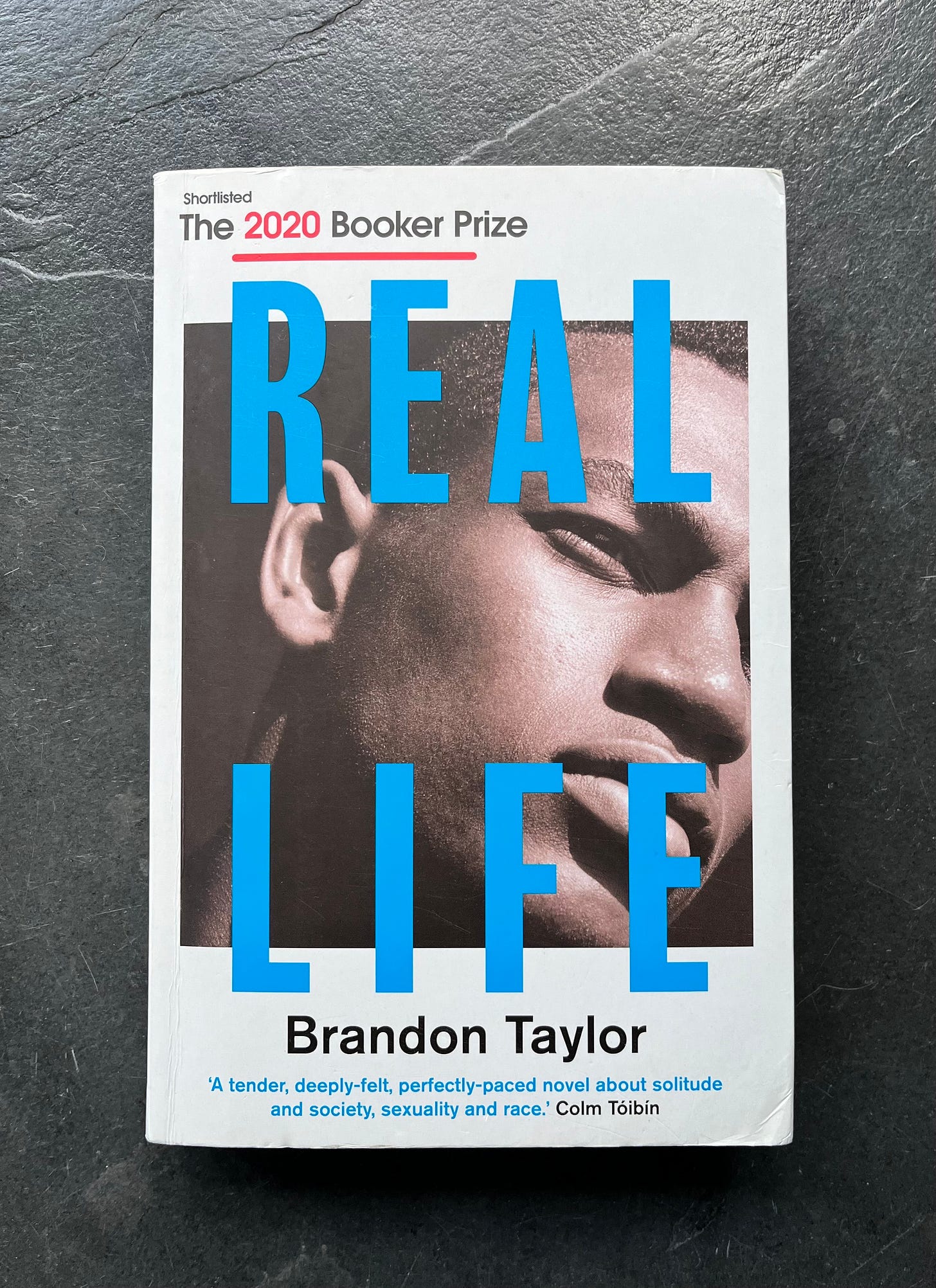

‘Real Life’ by Brandon Taylor

Wallace is a Black, queer man who is four years into his biochem degree in a Midwestern university town; a life that is far removed from his childhood in Alabama. Wallace’s father died a few weeks ago, but he didn’t return for the funeral, or tell his friends. For initially unclear reasons, he keeps a distance from them. He is wary of them, their thoughts and opinions. Resentment circulates in the group dynamic, but it is never addressed. The entire group's foundations are built on their love for research and science. Over the course of one end-of-summer weekend, the undercurrents of tension within the group come to head, and Wallace is confronted about his past and future.

I have mixed feelings about this book. I read it with my friend

, and we spoke extensively about how it was both brilliant and needlessly wordy. I will, however, start with what I did enjoy. Real Life is a campus novel about race and society. It is a story of racism that is absent from the word, instead extrapolating on the pervasive quiet microaggressions. Without being didactic, it explores the blatant injustice and discrimination that Wallace is experiencing at his predominantly white university, in a predominantly white Midwestern town. Taylor interrogates how racism is often misunderstood as overt violent outbursts by delicately portraying a life where Wallace is quietly, but consistently, treated like a second class citizen. Wallace experiences such extensive casual racism everyday that it just washes over him. Witnessing his resignation to being in this kind of environment is devastating.Taylor puts us inside Wallace’s head and makes us privy to his emotional turmoil in response to being constantly othered. Wallace is introverted and full of grief, and bearing witness to his intensity of emotions was tumultuous and intense. Often, this was made more severe by prose that was overwritten. The heaviness of being inside Wallace’s head, along with Taylor’s overwritten prose, was sometimes a marginally punishing reading experience, in a way I don’t believe was intended. Frequently, the delicate but arresting nature of Wallace’s emotions were mislaid to a torrent of words. It made it consistently challenging to get into the flow of the story, and a reader should never have to work that hard.

Unlike the prose, something which was intentionally disorientating was the exploration of the fine line between violence and desire. It was unsettling to read Wallace’s own relationship with affection be confused with violence as if to mirror his own experiences. There is a whiplash for the reader as we are thrown between the feelings of violence and desire, unclear where one ends and the other begins. I thought this exploration was exceptionally well done. My closing point, (which is entirely

’s that he texted to me mid-way through and influenced the rest of my reading experience), is how each chapter feels like a play.1 From setting the scene, to the heavy dialogue and the build up of tension, this pattern creates these repeatedly intense scenes that explore a meticulous study of race, grief and desire.Real Life was a mixed experience for me. Some chapters, where Wallace tells Miller what happened to him in his childhood, or when he plays tennis with Cole, were beautifully precise. But alas, this moving precision did not permeate the whole way through. I liked and disliked aspects of this novel in equal measure, and I am aware this style of writing is all about taste, so I would call Real Life a borrow. I have heard that Taylor’s more recent work has moved away from this style which makes me marginally more open minded to reading him again. If anyone has read both Real Life and The Late Americans, please give me a comparison!

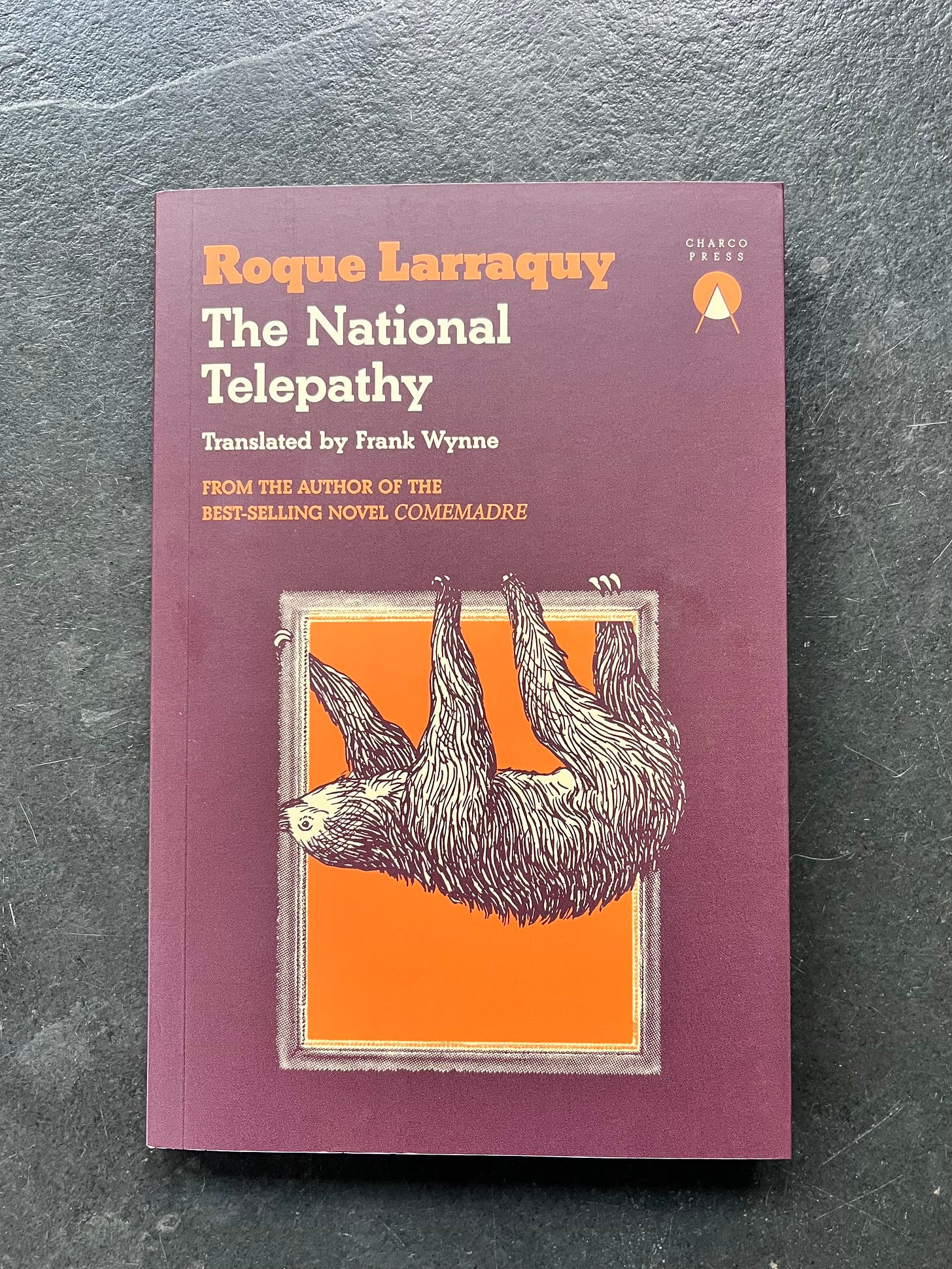

‘The National Telepathy’ by Roque Larraquy

In September 1933, the Peruvian Rubber Company delivers nineteen indigenous people from the Amazon to a businessman named Amado Dam. Dam wants to create Argentina’s first ‘Ethnographic Theme Park’ - a human zoo. However, among the human cargo is an unexpected surprise; a sloth who has the ability to create telepathic connections between people. When Dam discovers the sloth, who has the potential to explore the interconnectedness of all living things, he can’t help but view it as a business opportunity. What ensues is a satire of epic proportions about the illusion of the structures of civilisation, race and class when the observer is a man in a position of power.

The National Telepathy is an outrageously bizarre novel about how dangerous the white man can be. The book is perhaps best described by Larraquy about exactly what he wanted to explore;

‘I’m interested in presenting voices of white, cis, heterosexual, racist, conservative men, and through these voices, expressing their limitations in understanding the world. For example, in the novel, we have a character who embodies all of these traits and has the beautiful opportunity to access the consciousness and memories of a representative of an indigenous Amazonian people. After that telepathic experience…it didn’t change him much. I was interested in how racist discourse and the denial of diversity are a sort of prison of understanding the world, a degradation of perception.’ - Roque Larraquy in Eternal Cadence2

In a riot of imagination and magical realism, Larraquy explores how something with revolutionary potential will often be weaponised by these voices to ensure they can dominate and monetize. I was hooked by the absurdity of this novel from the first page. The language used to discuss the indigenous tribe is so dehumanising, it is captivating in its abhorrence.

The National Telepathy explores the view of a monster - which in this case, is someone who embodies patriarchal, homophobic, racist, conservative right views. Dam is not an unlikeable protagonist, which is likely the point. Larraquy resists making him an uncomplex or flat villain. Instead, he is someone full of contradictions, which make him unfailingly human. The structures of evil which Larraquy explores have been created by humans, so it is appropriate to explore them through the prism of someone's humanity. Dam is entirely unflinching in his perspective of the world, which makes for an in equal parts highly uncomfortable and unbelievably shocking read.

This is, in many ways, my ideal novel. Larraquy interrogates the structures of our world in a satirical fable about humanity's morality. So much of this novel is fictitious, but so much of it is also not. There is little distinction between what is fact and what is fiction, and I think this ambiguity is what achieves such an impressive level of unease for the reader. While a sloth with magical telepathic powers is not real, what it represents about our lack of understanding of indigenous communities and other ways of being, is. The National Telepathy is full of colonial legacy, references to Argentinian political landscape and the machinations of pseudoscience in circles of power. There is also an enormous amount of eroticism in this novel that I, truthfully, had no idea how to approach in this review. All I will say is - it’s both alarming and funny.

Much of The National Telepathy is a clever play on imagination which is difficult to discuss without ruining the fun of the novel. I loved how it made me think and the internet rabbit holes I ended up in several hours after putting the book down. I wish I knew more about Argentinian political movements to help contextualise some of the references to Peronism, so I now endeavour to seek out some fiction that explores it. If anyone has any recommendations - let me know. I would undoubtedly recommend this and call it a buy. It is both silly and serious, remarkably creative and captivating to read. I have to read Larraquy’s other work, Commemadre, now!

‘Memories of a Catholic Girlhood’ by Mary McCarthy

American novelist, critic and political activist Mary McCarthy had a turbulent childhood in the 1920s. She was orphaned at six-years-old, along with her three brothers, when her parents died in the 1918 influenza epidemic. They were left to a colourful and mysterious selection of relations, many whom they did not know. There were her Catholic and Jewish grandmothers, a wicked Uncle Myers who gave them a ‘Dickensian’ childhood full of abuse and Aunt Margaret who taped her mouth up at night to prevent ‘mouth breathing’. McCarthy chronicles her experiences with these bizarre and some, incredibly cruel, adults. Some of the experiences of the McCarthy children read like they should be fiction, but alas they are not. It is a tale of a life from a different time, a collection of essays about the experience of childhood and adolescence at the hands of people who don’t understand, or, love you.

McCarthy is an endearing narrator as she recalls the observations she makes about herself and those around her. Frequently being carted from one family member to the next, changing schools and struggling to maintain friends, McCarthy falls into this position of being introspective. Her lack of ability to ‘fit in’ at almost every point in her childhood means she is a defiant and curious child who is frequently questioning why things are the way they are. Perhaps where this is most intriguing is her experience with religion. Catholicism initially gave her first identity, one that she claims saved her, but this swiftly crumbled when she decided God wasn’t real and became an atheist, while at a Catholic boarding school.

While McCarthy’s experiences are central to the nine essays that comprise this book, many of them intimately explore the adults around her. She views them with great curiosity and this is evident through how she chooses to portray them. McCarthy dives into the personal history of many of her family members who are a collection of eccentric and withdrawn adults, looking after children they never expected, or arguably, wanted to. Up against the adults left behind to look after the children, McCarthy’s dead parents are always idolised. The life McCathy could have had with her parents is arguably a belief system she feels more strongly for than any other religious affinity.

McCarthy’s prose is witty and scathing. The strength of her voice fluctuates, but throughout remains the touchingly honest and curious perspective of a child. Her querying of religion, social structures and power dynamics remains throughout, describing a childhood characterised by powerlessness. Memories of a Catholic Girlhood is like a time capsule as these accounts occurred over a hundred years ago. I searched through the New York Times archives to find an early review of how this was received;

‘The vanities and ambitions, the resentments and misunderstandings, the small triumphs and the scarring disasters that marked her early years are set forth with remarkable candor [...] Talk about a Lost Generation sounds glib and becomes vague when you read this book about a writer who was harshly given every opportunity to become one of the lost, and yet went on to create in modern idioms a style based on classic Latin satire.’ Charles Poore, NYT, May 1957

Poore’s words stand true today, McCarthy writes with such remarkable colour and candor it is captivating to read. Poore’s reference to the Lost Generation is one that I would not have thought of myself, but feels incredibly appropriate here. McCarthy came of age in a time when many were irrevocably impacted by the war, suffering great disillusionment and suffering. McCarthy’s childhood may not have been lost to the war, but it was certainly lost to all those who failed to care for her. McCarthy’s recountment of her childhood is fascinatingly captivating. I would call Memories of a Catholic Girlhood a borrow and recommend it if you enjoy reading about eccentric characters or are curious about all the variety that can exist in one family tree.

‘Sons, Daughters’ by Ivana Bodrožić meditates on the confinement that can be felt within the prison of our bodies. With three separation narrators, this polyvocal novel explores the interconnected stories of three people who arrived into this world as girls, and are united in their search for freedom from the confinement of bodies, sex and gender.

Sons, Daughters begins with our initial narrator, Lucija. She is in hospital, paralysed, with locked-in syndrome. She is unable to communicate except with the vertical movement of her eyes. While bedridden, Lucija is often regarded as if she is not there and does not have a rich emotional life. Thus, as she lives the dehumanising experience of being manhandled and ignored, Lucija thinks about her life before. In dream-like prose, she recounts her memories; of her family, the Croatian War of Independence and her boyfriend. It is through Lucija’s perspective we first learn about our other narrators. Her mother is visiting her, which she despises, but her boyfriend is not, which she agonises over. Unable to articulate any of the nuance in how she feels, Lucija is trapped, completely cut off from the world;

‘I am always wondering, ever since I found myself in this condition, what kind of an impact it has on people, being faced by someones boundless isolation’ p.105 in Sons, Daughters

Dorian, her boyfriend, is our second narrator. He provides an account of who Lucija was before the accident, detailing their relationship and offering some retrospective insight into Lucija’s relationship with her family. Dorian recalls his own tumultuous relationship with his body;

‘For a long, long, time, I could not accept that nature had given me the gift of being a person who has experienced what it means to be a woman in this world [...] bounded by a profound and total understanding of a world that has kept [...] us down since our first cry’ p.191 in Sons, Daughters

Through his perspective, we learn about the shame and abuse Dorian has experienced while navigating transitioning. Despite the legal framework in Croatia protecting the LGBTQ population, societal attitudes remain reluctant to accept their existence. 84% avoid holding hands with their same sex partner, which is over 20% higher than the rest of Europe. Dorian frankly addresses his experience of feeling trapped and ostracised by his body.

Our third and final narration is from Lucija’s mother, which is the final piece in the puzzle to understanding these intimately intertwined lives. She takes us back to her childhood, recounts her life that has been characterised by misogyny and abuse. She resents her pregnancies and the curse of being a mother in such a violent, male-dominated society. Dorian and Lucija view her as a one-dimensional, unforgiving woman. However, we retrospectively learn about why she behaves the way she does and that she has a rich emotional life, just like the others;

‘A little boy and a little girl, like what we had been long ago. A young man and a young woman, now a grown man and a grown woman, yet all four of us together worth less than Masculinity. What this all comes down to is nothing more than a slimy stretch of skin between the legs’ p.218 in Sons, Daughters

Sons, Daughters profoundly meditates on how we can never truly know someone, because there are no identical lived experiences of the world. What unifies these perspectives is the desire for freedom, which they cannot access because of the limits of their bodies. The novel gives insight to three generations in Croatia who have experienced extensive socio-political change in their lifetimes. Bodrožić says Sons, Daughters was written as ‘an apology to all those who are forced to live, invisible, in this society and this world, convinced since childhood that they do not deserve love, dignity, and, above all, freedom’.3 It speaks to the idea that the violence and neglect society inflicts on marginalised people affects us all. While worlds apart in their experiences, they each share a sense of powerlessness because of the bodies they are in. The novel tenderly examines the role divisiveness plays in our societies and how we are much more similar than we think.

I loved how this book grew on me. I was initially unsure of the narration style but once I began to understand all that Bodrožić was trying to explore, I was enthralled. Tender and sincere in its messaging, the novel impressively connects three different experiences in their search for freedom in this world. In the end, I thought what the narrative was articulating was beautiful. I would recommend this and call it a buy! It is a novel characterised by introspection and the misunderstanding of the emotional complexity that lives within all of us, even in those we would like to believe otherwise.

‘Brandy Sour’ by Constantia Soteriou is anchored by one omnipresent protagonist, The Ledra Palace Hotel. The hotel is located in central Nicosia and was built in 1950 to signify economic prosperity and hope for Cyprus; it was the largest and most glamorous hotel in the city. That is, until 1974, where it became a United Nations base. Since 2004, it has been the crossing point between the controlled territories, ‘a landmark that reflects Cypriot history’ and its turbulent twentieth century.4

Brandy Sour is told in vignettes about individuals who are all connected to the hotel. From cleaners, porters and staff, to guests, a King and the UN officers who made it their barracks, they are all reluctant actors in history. Each of their experiences with the hotel mark a moment in its lifetime. These fleeting insights into the lives of those touched by the hotel create a personal and unique portrait of conflict and division. The history and politics of Cyprus is seen through the lives of the ordinary people who lived through it to help create a alternative understanding of the island;

‘It tells a different story of Cyprus - as a country that’s not just a tourist destination and not just a place that experienced a war. I know those aspects are true, but I wanted to present a different picture in my book; I wanted to show people who enjoy their lives, who drink, who eat, and who lived a full life in their country…the many faces of Cyprus' - Constantia Soteriou in conversation with nb magazine

Each vignette is a moment in someone's life, characterised by a relationship with a liquid, most of which are drinks. The drinks give an insight into the culture and tradition that is being threatened because of the conflict. Recalling their individual relationships with them invoke memories, recall routines and reflect on desires. We witness people's interest in drinks change overtime as an idyllic island becomes the centre of an unravelling conflict. This remarkably ingenuitive economic snapshot from Soteriou takes something as specific as individuals' relationships with drinks changing to reflect the emerging despondency from Cypriots, as they witness their homes get destroyed.

Soteriou’s approach to storytelling is rich and moving. I loved the format and the use of something as personal as the drinks we choose for comfort, joy and solace as a vehicle to understand the conflict. The hotel as an anchor throughout was more poetic and poignant than I could have ever anticipated it to be. This anthropomorphistic approach was deeply evocative, one that was arguably more moving than what could have been driven by having a human protagonist. There is a poeticness to the endurance of buildings in conflict, and The Ledra Palace Hotel witnesses so much hope and loss in its lifetime. It is perfect as the centrality of Brandy Sour in exploring the dramatically changing landscape of the island.

The concept of Brandy Sour is imaginative and thought provoking about what storytelling about conflict can look like. Soteriou’s prose is delicate and intimate, discussing a conflict without ever mentioning political impetus or detailing dead bodies; instead, through the intimacies of ordinary people in their daily life. In as little as a-hundred-and-four-pages, Brandy Sour says so much about Cyprus and their recent history.

Soteriou’ hopes from reading Brandy Sour people understand Cyprus ‘isn’t monolithic’ or a holiday destination, instead ‘full of people, history and traditions’. Truthfully, Brandy Sour is my first encounter with any Cypriot history or culture, and I can attest she has achieved what she wishes. I have come away from reading this novel feeling I have learnt about Cyprus through the people who live there. I don’t know the specifics of the conflict, but I know how it made people feel, and therein lies the everlasting brilliance of fiction and the opportunity it gives us to learn. I highly recommend this as a truly creative approach to discussing conflict and the impact of political decisions on the lives of ordinary people. I rarely come across fiction that explores conflict in such a stylistically poetic way as Brandy Sour does. This is a buy, I thought it was brilliant and unlike anything I have read before.

‘Azúcar’ by Nii Ayikwei Parkes

Set on a fictional Caribbean island, Azúcar, which means ‘sugar’, is a story from two alternating narrators. Emelina and Yunior are both confronting the idea of where they feel most at home. Emelina is the great-grandaughter of Diego Soñada Santos, head of the Fumazero family that produces the world famous Soñada Sun rice. Emelina has been raised in the US, and travels to the island of Fumaz for the first time for a family gathering. Yunior, on the other hand, is Ghanaian and came to Fumaz aged thirteen on a scholarship and never left. He comes to view Fumaz as his home, and becomes a successful musician and unearths a love for food. Yunior’s love of food and gardening results in him gaining a position of significance to help Fumaz’s food crisis and agriculture dry spell. The novel follows their own journeys with the island of Fumaz, overlapping when they are brought together to keep the myth, and production, of the famous Soñada Sun rice alive.

Azúcar is constantly grappling with the theme of home; is it a place, person, where you were born or where you choose to be? It is, in many ways, a love letter to migrants and all they bring to communities. Neither Yunior or Emelina are Fumaz by birth right, but both find identity, purpose and connection to the island. It comes as a shock to them both, in different ways, when they realise they do not feel at ‘home’ in the places they were born;

‘He had three weeks left in Accra, but he was already missing it, he was missing it because, watching the wonderful chaos outside, the energetic dancing, the tongue-in-cheek jama chants [...] he realised that he was observing like a tourist’ p.62 in Azúcar

Despite its sweetness, the novel tackles a large array of topics from colonial legacy to food insecurity in the landscape of the late 20th century. Fictional Fumaz reads like an amalgamation of all the political and economic issues the Caribbean Islands have faced in the last century. With so much to address in less than two-hundred-pages, Azúcar has an impressive scope. Arguably, it was too much. It often felt like the exploration of the political economy that Parkes so evidently wanted to include, was rushed in order to reach the union of Yunior and Emelina quicker. Entire relationships felt hurried in order to arrive at the one we know is coming. It felt disingenuous to bring in characters with quite minimal development as place holders. Azúcar heading to this idealised ending felt all too kumbaya for me. I don’t enjoy stories where everything falls into place in the end, because that is not indicative of real life.

While the sweetness of this fable was too excessive for me with its predictable ending and surface level romantic relationships, the prose was quite enchanting. Though at times overdone, Parkes' writing was rich and lyrical. I have never come across a book that describes food, and the art of growing it, in such a vibrant way.

Azúcar has a fairytale nature with its love for food, music and family. It is very out of my wheelhouse to read something that relies so heavily on sentimentality and the belief that it all comes together in the end. I found this thrust of the story frustrating. I think this novel could have taken an extra hundred pages and be developed into the generational story it so desperately wants to be. Parkes prose has whispers of Gyasi’s from Homegoing, and I can not stop thinking about what Azúcar could have been with a longer word count and a bit more grit! Alas, it is unfair to measure up a book on all it could be, rather than what it is, because that is lazy reviewing.5

What Azúcar is is a sweet fable about what it means to call a place home and how we might go about finding it. While the saccharine nature of the story was too much for me, I did enjoy reading it. I would recommend this to anyone who enjoys stories about the myths that keep communities alive and the concept of fate. Honestly, if you’re looking for a book that’s unchallenging yet intriguing, this is it. I would call Azúcar a borrow! Despite some of my criticisms of the pacing, I am intrigued in reading Parkes’s poetry!

And that concludes my February Reads! My favourite book of the month was ‘Brotherless Night’, closely followed by ‘Sons, Daughters’.

My first read of March is ‘The Savage Detectives’ by Roberto Bolaño. It’s finally happening, I am reading my first Bolaño! I have no comments yet, I’m only 100 pages in.

End Notes

Earlier this month,

asked me to share my five things with her, which I loved! One of my five was a documentary, Dahomey, which is about the return of some objects from a museum in Paris to Benin.Speaking of documentaries, I watched two others in February which were excellent; Escaping Utopia and Gaucho Gaucho. Two very different vibes but very good watches. The cinematography especially in Gaucho Gaucho is just sublime.

The Women’s Prize announced their 2025 Non-Fiction Longlist which is exciting! I’m intrigued by;

Tracker by Alexis Wright

Private Revolutions: Coming of Age in a New China by Yuan Yang

The International Booker Prize announced their 2025 Longlist! I, famously, read the shortlist last year and hated it. I proclaimed to have better taste in translated literature than the judges, and I still stand by this. However, it is a new year with new judges, and I like the look of this list. The only one I’ve read is Hunchback!

But, I have copies of:

On A Woman’s Madness by Astrid Roemer (I bought this last year to aid my goal of reading a book from every South American country!)

Small Boat by Vincent Delecroix

Solenoid by Mircea Cǎrtǎrescu

On the Calculation of Vol I & II by Solvej Balle

Heart Lamp by Banu Mushtaq

The Book Of Disappearance by Ibtisam Azem

Do any readers have any requests for which books I read first from this list?

My brilliant friend

has launched a podcast with called ! I am not really a podcast girl (I prefer to read, a surprise to no one) but this I will listen too! Tembe is whip smart and hilarious - I will happily listen to her and Mbiye talk all day about books, theory and culture.

Let me know your thoughts:

❀ What have you read and enjoyed in February?

❃ Have you read any of these books? Would you like to?

❁ Do you have any book recommendations for me based on the themes of this month?

☼ Are you eyeing up any books from either longlist?! Maybe you have already read some? Maybe you hate literary prizes? Tell me!

Thank you, always, for reading.

See you next month,

Happy Reading! Love Martha

If you know someone who is wanting to expand their reading life in 2025, share this newsletter with them!

Catch up on what you might have missed:

And what I was reading this time last year;

Remember to subscribe if you enjoyed this and want to receive recommendations straight to your inbox!

I endeavour to always introduce you to books that don’t get coverage elsewhere - that is a promise.

I translated this interview using Chat GPT so, I am sure it is not entirely accurate but I’m sure the essence is there!

Quote taken from ‘in place of acknowledgments, an apology’ on p.255 in Sons, Daughters by Ivana Bodrižić

and I am anything but a lazy reviewer!!!!

Fantastic average this month! Heavy on the ‘buy’s—we love to see it.

I’ve read all of Brandon Taylor’s books, so I can confirm they all have that je ne sais quoi we discussed. Although, both The Late Americans and Filthy Animals are interconnected short stories, so the execution is a bit different!

Very interested in Brandy Sour, The National Telepathy and Brotherless Night!

"I don’t enjoy stories where everything falls into place in the end, because that is not indicative of real life." I felt I was the only one to think that way and my friend often make fun of me because of this but I'm glad to read that we share this pov! Thanks again for sharing with us your diverse reading. I have already shelves "Brotherless Night" and "Brandy Sour" thanks to you!