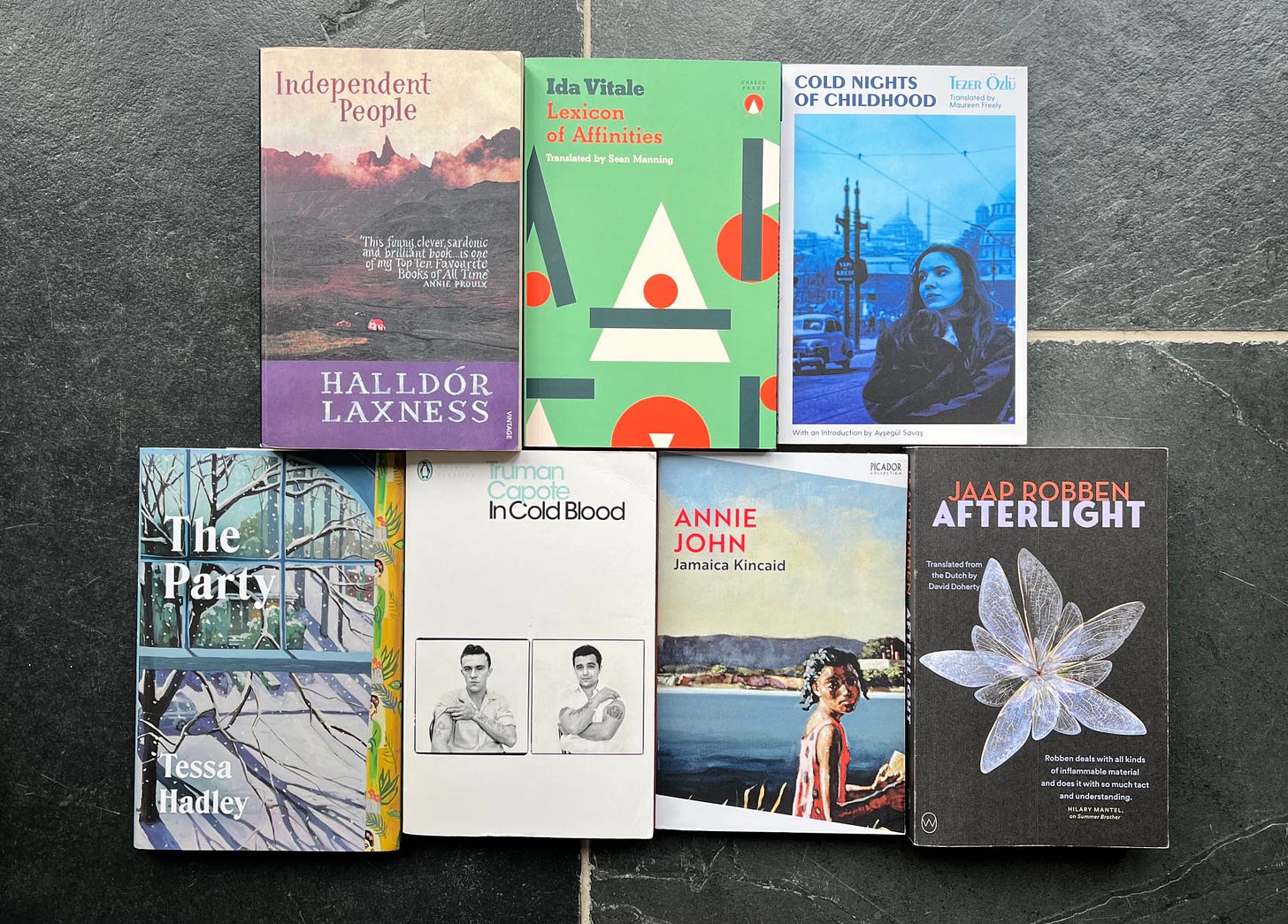

Welcome to ‘Martha’s Monthly’, January Reads edition! January felt like it lasted forever, yet I only read seven books? I seem to be in a phase of reading less than I normally do, the cause is unknown!1

Several of the books this month were coming-of-age stories, tales of growing up and the tension that exists between childhood to adulthood. While others discussed growing old and the reflection that occurs when you have been fortunate enough to live a long life. All the novels were deeply human, exploring existence through secrets, relationships and tragedies.

To see the translated reads from January on Martha’s Map, including authors from Iceland, Uruguay, The Netherlands and Turkey, click here.

For those who are new, buy, borrow, bust is my recommendation key: Buy = I loved this book and highly recommend it. Borrow = I liked this book and think it is worth a read. Bust = I wouldn’t recommend this book from my reading experience.

‘Independent People’ by Halldór Laxness

Our protagonist, Bjartus, is a sheep farmer. After serving eighteen-years to a master he despised, all he wants is to raise his flock unbeholden to anyone. He is, to the determinant of his wives, children and sheep, obsessed with the goal of financial independence. Bjartus is radical in his interpretation of independence and he raises his family in severe isolation in principle. He demonstrates a remarkable lack of humility and everything he does is contributing to his goal of a life detached from others. It seems that no one can challenge Bjartus’ way of thinking, except Asta Solillja; the child he brings up as his daughter. When he throws her out of the house after discovering she has tarnished his name, his stony will begins to crumble.

Bjartus' goal of independence is initially admirable, but begins to feel increasingly unhinged as his life progresses and becomes significantly harder. He is not a nice man; he is cruel, unforgiving and seemingly addicted to hardship. He cares for the principles of things, rather than the things themselves;

‘The strongest man is he who stands alone. A man is born alone. A man dies alone. Then why shouldn’t he live alone? Is not the ability to stand alone the perfection of life, the goal?’ p.446 in Independent People

To put it simply, Independent People is a miserable story. It deals with the struggles of poor Icelandic farmers who are trying to survive in inhospitable landscapes. Set in the early twentieth century, the novel is a portrait of a nation on the cusp of modernity and a culture that is on the precipice of being lost in time. Laxness explores the tensions that emerge when society is more focused on aggressive individualism than community. Bjartus embodies this emerging level of self interest under a modern economic system. At a time when Iceland was experiencing significant socio-political-economic change, Laxness interrogates that both paths of modernity and rural lifestyles come with sacrifice and loss.

Bjartus’ independence is in stark comparison to the large migratory movements to the United States. He criticises them extensively, saying they’re naive and abandoning the land. Laxness considers how the life Bjartus has chosen does not morally separate him from these people, despite what he’d like to believe. His obsession with solitary self-sufficiency condemns him to a life of unimaginable suffering; one that is a choice. This tension between rural and ‘modern’ life, independence and interdependence, characterises the novel. There is an exploration in both about the degrees people isolate themselves from others in the name of independence.

The novel develops from a young Bjartus’ idealistic outlook on life to a man who is in the position of losing everything because of the pursuit of an ideal. Bjartus’ dream of independence never quite amounts to what he thinks it will, because ultimately his isolation results in having no social mobility. Bjartus’ natively believes that principle and determination will change his social standing. Instead, to the detriment of his family, he creates a cursed generation.

This was a challenge to read. Everything in this novel is intense; from the oppressive landscape to a heartless protagonist. Some passages were full of emotion and beauty, while others were tedious and very descriptive about sheep. Despite this, I liked it. Weeks after putting the book down, I often find myself thinking about how Laxness used the characterisation of Bjartus to critique the idea of independence. Is true independence possible under these systems, or is the tension between it and interdependence unavoidable?

Independent People is simultaneously so brilliantly clever and painful to read. I would call it a borrow. I would recommend it to anyone who would like a challenge and is interested in a book that meditates on what it means to be individualistic, have self-interest and participate in community.

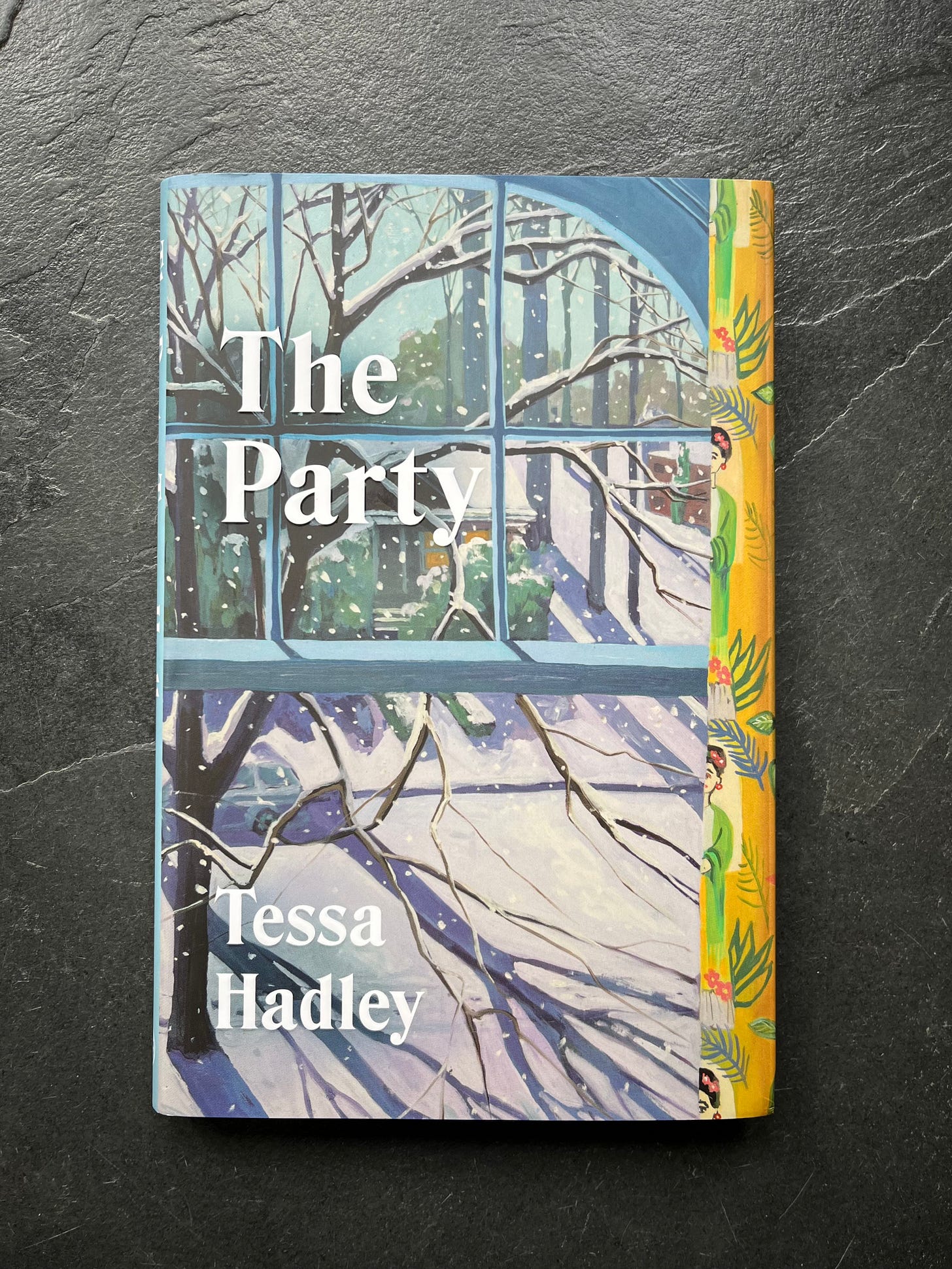

‘The Party’ by Tessa Hadley

After the density of Independent People, I needed a palate cleansing read. The Party is a coming-of-age novella about two sisters, Moira and Evelyn, in post-war Bristol. While only two years apart, what exists between Moira and Evelyn is familiar to us all with siblings; a hierarchy. There is an unbalance of power, as there always is, in sister relationships. Evelyn admires her older sister and Moira resents her for it. Evelyn desperately wants to be let into the life she believes Moira has, while Moira tries to reinforce a distance between them.

The Party commences with Evelyn striking out on her own to go to a party, unbeknownst to Moira. The atmosphere is expectant with hopes and dreams about the life they could have. The future, theirs and the nations, is in flux and this youthful unbounded emotion creates a palpable expectation that this night could change them forever. While Evelyn overestimates Moira’s resentment to her surprise appearance, they end the night together and have a shared escapade of girlhood. But underneath the glitter of youth and the disappointment of when the night is over, is the domestic details of their home and the realisation that life is full of dissatisfaction and mundanity.

‘Weren't we all helpless to defend ourselves, against whatever depredations and losses and suffering were in store for us?’ p.67 in The Party

The Party is a mediation on youth versus old age; the unknown and the known. Evelyn and Moira are on the cusp of adulthood and over the course of a single evening, they fall head first into it. The sisters have the defiance of youth, to be unlike everyone else they know who is ‘old’. They are comfortable at home but equally desperate to leave, a battle of desire that dominates so much of youth. On the night they pass this (metaphorical and literal) threshold from childhood into adulthood, they are forced to reckon with that, perhaps, mundanity is ok. I didn’t find this tone depressing, instead familiar in the transition of being young and growing up. We all, at some point, have had to reckon with the mis-sold dream of expecting constant remarkability in our adult lives.

The novella is a portrait of a family in a different time, an exploration of familiarity and predictability after a period of turbulence. Perhaps the post-war nature of the novella is why, in the end, there is this found comfortability in the trivial humanity of it all. The themes of class and gender are explored on the periphery through their parents. Their mother is trapped in a performance of domesticity to keep up appearances while her husband unabashedly cheats on her. Yet, she is still beholden to these tasks as her only value. She represents a life trapped between what is expected of her and who she would like to be. Her portrait is one I would have liked more nuance in her character about the expectations vs reality of life. However, the mere existence of their mother operates as a marker of time changing for middle class women in British society. Moira and Evelyn know they don’t want her life of performing domesticity and having no agency.

I read several reviews comparing The Party to Keegan, and several more exclaiming profanity that anyone dared compare the two. I lie somewhere between the two. Hadley’s prose is not dissimilar to Keegan’s. Both The Party and Small Things Like These are novellas that use the intimacies of day-to-day domestic life to comment on the structures of our world. Both use the perspectives of women to question the constrictive experience of a society heavily characterised by religion and the patriarchy. While I would argue that Keegan achieves a more profound level of emotion within her prose, I don’t think the comparison is as atrocious as some suggest. If you like Keegan, you’ll probably like this.

I enjoyed the character driven nature of The Party and the subtle shift we witness in Evelyn and Moira’s relationship from a rigid hierarchy to more egalitarian. I thought Hadley’s prose was skilful in both the surface and deep intimacies of life. While I wouldn’t go as far as to say I was immensely enthralled by this novel, I found it pleasant to read. I would recommend The Party and call it a borrow! The Times described The Party as ‘Sex, Class and Sunday Roasts’ and while hilariously reductive, it is also accurate.

‘Annie John’ by Jamaica Kincaid is a tale of transitioning from girlhood to womanhood in 1950s Antigua. Annie is a defiant and spirited only child who is inseparable from her mother. Their relationship is full of deep affection and her constant inquisitive nature is celebrated. The relationship is idyllic, and we can sense how much Annie values her mother through her expression; ‘how important I felt to be with my mother’. With a ‘the-world-is-my-oyster’ outlook on life, Annie charms the adults around her and dominates her peers with her intelligence and astuteness. Annie, modest about her accolades, has a remarkable level of self assurance and is not afflicted by anxieties about the future;

‘We were sure the much talked about future that everybody was preparing us for would never come, for we had such a powerful feeling against it, and why shouldn’t our will prevail this time?’ p.47 in Annie John

Annie is, in every sense, a child; confident about the world and herself. However, when Annie turns twelve, the world becomes more complicated. Her period arrives and she begins to feel alienated from her friends, family and sense of self. She starts to become increasingly disappointed by herself and those around her, never quite fitting in. Her mother ceases to be a source of unconditional adoration and takes on a new guise of critique. Annie’s curiosity becomes punishable and she is suddenly expected to conduct herself differently. As Annie and her mother undertake a battle for autonomy, she becomes subdued, all because there is an expectation that things should be different, now that she has ‘grown up’.

I read this with

and we both absolutely loved it. Kincaid has written a wonderfully poignant exploration about coming-of-age, and how much of a destabilising experience it is. Annie John addresses the deeply familiar experience of everything you thought you knew unravelling. Kincaid captures Annie’s childlike curiosity and the confusion of adolescence exceptionally. Annie embodies this tension between feeling tethered to her family and wanting to break free. She feels simultaneously suffocated by her mother and desperate for her affection. The novel epitomises the complexity of wanting to be your own person, but not quite knowing how.Many aspects of Annie’s childhood are characterised by colonialism and we witness this tension between the impact of British colonial rule on the personal and collective identity of Antigua. This is embodied most by the standards Annie’s mother has for her and the education she receives. Throughout, we can perceive that the British education Annie is receiving undermines local traditions and values, it creates a chasm between them and the land.

and I both discussed how we would have liked more exploration about the late stages of British colonial rule in Antigua, but ultimately appreciated that this would not be the case because our narrator is a child. Kincaid makes us privy to Annie’s perspective of colonial rule, one of innocently observed day to day glimpses, instead of any societal or political commentary. Despite this, we still get a strong sense of the tension between the identities even three-hundred-years after Antigua was initially colonised.Annie’s characterisation was spectacular and I revelled in her cheek. Her confusion about growing up and the idea of never truly being known by another person felt touchingly familiar. I loved how Kincaid approached exploring a hostile mother-daughter relationship, illuminating the impact of generational trauma and expectations on how love can change to become something unrecognisable. Throughout, Kincaid explores the impact of having a negative relationship with your mother, along with the (sometimes) pervasive belief that maternal love is expected to evolve from affection to intimidation under the guise of growing up.

‘It was a big and solid shadow, and it looked so much like my mother that I became frightened. For I could not be sure whether for the rest of my life I would be able to tell when it was really my mother and when it was really her shadow standing between me and the rest of the world.’ p.102 in Annie John

I loved Annie John and the earnest conversation Kincaid orchestrates about the struggle of growing up and maternal relationships. This was my first novel of Kincaid’s and I am deeply impressed with her writing. I would absolutely recommend Annie John and call it a buy! It was funny, sincere and I enjoyed every moment with it. Annie John reminded me of Abyss in how it explored the perspective of a child about an adult’s behaviour within our often hostile world.

‘Lexicon of Affinities’ by Ida Vitale

Ida Vitale is a Uruguayan poet, translator, essayist and literary critic. Born in 1923, she played an important role in a group of twentieth-century Latin American writers called ‘Generation of 45’, who had notable influence on the culture of the region. She fled to Mexico in 1973 for political asylum after a military government took power in Uruguay.2 Today, Vitale is a-hundred-and-one and is the last surviving member of Generation of 45. She has won countless prizes and honours, dedicating her entire life to the power of words.

Thus, Lexicon of Affinities is Vitale's ingenuitive approach to memorialising her life. It is a hybrid of forms; part memoir, poetry and dictionary, which all come together to explore Vitale as an individual. It begins with a ‘Statement Of Intentions’ where Vitale writes;

‘The world is chaotic, and fortunately, difficult to classify, but chaos, matter susceptible to wondrous transformation, presents the temptation of order. [...] We live in search of the best system to organise it all, to understand it at least. Until that one irrefutable order comes along, the most innocent option is alphabetical. So I will limit it according to my affinities, selecting the lexicon that crystallizes, arbitrarily, around each letter: not all of them, only those that sing to me’ - p.1 in Lexicon of Affinities

Essentially, the book is full of entries that are a response to a word, catalogued under a letter. Each chapter is a different letter of the alphabet. There is no plot and no narrative to follow. Lexicon of Affinities is a book of Vitale’s emotions, memories and definitions.

This, truthfully, took me a while to read. With so much different material to constantly consider, I often only managed to read a few pages at a time. There is so much variety, and lack of uniformity, in this novel.

Some words just elicit a single sentence definition;

Reading

‘A burning mirror where what we consume consumes us’

p.185 in Lexicon of Affinities

Or a poem;

Life

‘Hollow towering column,

Life.

But close to the ground, inside

- like a dove in a dark nest -

Hope.

p.116 in Lexicon of Affinities

While others, such as the word ‘bus’, provoke Vitale to remember her initial years living in Mexico. All the words circle around the themes of friendship, travel, literature and family. She recollects many of her friends who have now passed and the variety of places she has lived across the world. Vitale’s cataloguing of her life in words was fascinating and incredibly clever. It is an alternative approach to the memoir, and made me think extensively about how I would use language in such a way to reflect my identity and beliefs. The level of intimacy and mystery that Vitale manages to achieve through this format was enthralling. I simultaneously felt like I knew her personally and not at all. Which, I assume, is the sweet spot for any artist.

This is an incredibly hard novel to review because it is so varied. Arguably, it is not really a novel at all and instead a collection or a diary. Lexicon of Affinities is thought provoking in the most literal way. It ruminates on how each of our individual lexicons would look, because our own interpretations and relationships to language are so uniquely different. There could be no two iterations, because everyone is an individual. I think that is ultimately what Vitale was meditating on as she categorised her life in words.

Occasionally, I lost interest with some anecdotes, but I always got pulled back in eventually. I think with the nature of the format, it would be unlikely to be captivated throughout. However, it remained consistently poignant and poetic. I think I would recommend this to anyone who enjoys ruminating on our relationship to language, specifically how we interpret and categorise words. I would call Lexicon of Affinities a borrow. I consider it worthwhile to read the artistic reflection and interpretation of the world from someone who has lived such a long and unique life. Vitale’s outlook on the world is reassuringly optimistic, which feels comforting considering how much change she has witnessed.

‘Afterlight’ by Jaap Robben tells the story of one woman, Frieda, at two different times in her life. In a narrative of alternating point-of-views, the novel follows both Frieda as a recent widow who is about to become a grandmother, and her youth as a free-spirited florist.

We are initially introduced to Frieda when her husband suddenly dies and she finds herself alone, for the first time in decades, aged eighty-one. After being moved into a care home by her son, Frieda is struggling to adapt to a new way of life with no one familiar around her. She finds herself thinking about an event from her youth, one she has kept secret for decades and is buried deep in her past.

Frieda grew up in a strict Catholic environment in 1950s The Netherlands. When working as a florist, and living at home with her parents, she meets Otto on a winter walk. Otto is married, but takes an immediate interest in her, and they fall in love. Frieda and Otto have a whirlwind affair that comes to a crashing halt when Frieda falls pregnant, out of wedlock and with a married man. Her pregnancy is a scandal, one that drives a wedge between Frieda and Otto, her parents and the town. Frieda is forced to fend for herself in dire conditions while heavily pregnant. Devastatingly, when she finally gives birth, she never sees the baby again. Kept in the dark about what happened, Frieda is unable to be the mother to the child she was not supposed to have. The shame and fear orchestrated by the Church prevent a traumatised Frieda from ever speaking about what happened to her. But the grief for her lost baby has never left. Only in the solitude of the care home is Frieda forced to reckon with the sorrow of what happened to her, and her child.

Afterlight was a profoundly moving novel about a woman's existence as it follows her both growing up and growing old. I loved the dual narrative of young and old Frieda, both struggling in the face of isolation. Frieda’s characterisation is beautifully complex as we begin to intimately know her at two different points in her life. There were times within the alternating narratives where it was hard to believe it was the same person; both young and old, naive and wise, but Frieda’s resoluteness remains the same. We are meeting her, in many ways, at the beginning and the end of her adult life, and it is hard to imagine what took place between these two versions of her. Nevertheless, as Afterlight progresses, we begin to understand how the trauma of Frieda’s first pregnancy drastically affected her nature for the rest of her life. It is truly heartbreaking to read.

‘Life always went on, for everyone’ p.252 in Afterlight

Throughout, Robben unflinchingly interrogates the real life experiences illegitimately pregnant women had in the 1960s.3 Outcast from society and given no agency over her body or her baby, Frieda was dismissed and ignored. Afterlight interrogates the shame and fear that occurred for these women in strictly Catholic societies. Robben strikes a tone of both an indictment about how inhumanely they were treated and a compassionate tale about the scope of motherhood. The novel addresses that while Frieda became a mother again later in her life, this does not eliminate her first baby and first experience of motherhood. Equally, Afterlight suggests that old age is not synonymous with moving on, Frieda has never forgotten. It is a novel that is intimate and haunting about every mother whose child was taken from them.

Afterlight was so beautifully moving that I am finding it hard to articulate the emotional experience of reading this book. The weaving of the narrative, the climax of the story and the characterisation of Frieda were all remarkable. I enjoyed the novel so much, completely transfixed by Frieda looking for the answers to the questions she has had her entire life. Frieda’s experiences with love and loss are deeply human and utterly heartbreaking. I was lost for words when I finished Afterlight, and a few weeks later, I still am. I would absolutely recommend this novel and call it a buy. Afterlight is for readers who enjoy stories of hope. I so deeply wish I could express more eloquently how this novel made me feel, but for now this is all I can muster. It really knocked the wind out of me, in the best way, and I have thought about it every day since. There is a lot of grief in this story, but a lot of hope too. Robben beautifully moves between the two, articulating how a life is so heavily characterised by both emotions.

‘Cold Nights of Childhood’ by Tezer Özlü is a semi autobiographical novella about a woman's struggles with herself and society. Our unnamed narrator is moving in and out of psychiatric wards where she is being forced to undergo electric shock treatments. It is an unflinching portrait of a woman's psychological struggle and a clash between her and the repressive and rapidly transforming society of 1950s Istanbul. After almost 2,000 years as the capital of three great empires, Istanbul became a new republic's second city. The streets in which our narrator lives are steeped in the past. Both our narrator, and Istanbul, are struggling with their identities, unsure of what the future may bring or how to distance themselves from their past.

This novella is set in Paris, Berlin and Istanbul, in the search of freedom and love, each setting is blurred into one. This stylistic choice conveys a sense of fleetingness through the protagonist's suffering with mental illness. We appear only when our narrator begins to struggle with her depression again and is sent for treatment. It is not her whole life, but it is what we are privy to. It is demonstrative of how she is judged and perceived as a woman being moved in and out of psychiatric wards.

Cold Nights of Childhood felt deeply authentic in its perception of a woman's struggle with depression and the dramatic societal changes happening in Istanbul. Özlü’s prose is beautiful and chilling in how it portrays the attitudes to women’s mental health in the 1950s. In and out of the psychiatric wards, she is subjected to misogyny, continually sectioned by those close to her, instead of having any opportunity to exercise agency. The precarious lyrical prose is poetic in its exploration of a life lived between two different parts of history, two different states of mind. She is on a quest for freedom in the face of repression; from depression and society. You cannot help thinking what she desires to escape more, or which is more suffocating? The villain in Cold Nights of Childhood is not her depression, or the psychiatric wards she is subject to, but the restraints of bourgeois society in Turkey.

The novel is described as a descent into a woman's madness, which would naturally make readers assume the narrative is incoherent, but I found the narrator's voice full of clarity about the world she lived in. Even as the narrative jumps between time and place, I never felt confused in what she was trying to communicate. I was constantly enthralled in what she had to say, often meditating on what it means to be alive;

‘Instead the real world into which we must descend stands before us like an alien object. Like the globe they bring out in geography class. No one mentions that life is none other than the days, nights and seasons through which we pass. We sit there waiting for the sign. Preparing. For what?’ p.22 in Cold Nights of Childhood

I have seen Cold Nights of Childhood be compared to Plath’s The Bell Jar and I would agree, and go one step further and say, this is better. I thought it was more compelling and emotive. I found the narration arresting as I sat for one afternoon in the hold of this dizzying stream of consciousness. Özlü’s prose is beautifully objective, intense and gentle all at once. While there were times I was unsure of what was going on, I enjoyed every moment of it. I would recommend this and call it a buy. Cold Nights of Childhood is for those who enjoy lyrically ambiguous prose and the unflinching exploration of a life characterised by the struggle of depression.

‘In Cold Blood’ by Truman Capote reconstructs the 1959 murder of the Clutter family; a Kansas farmer, his wife and children. After hearing about the murder, Capote travelled to Kansas to learn about the case in real time as it unravelled. Capote wanted to experiment with a new form of non-fiction, or as he called it, a ‘literary experiment in prose narrative’.4 In Cold Blood is Capote’s study of the murders and the subsequent investigation. Controversially, the centre of his study are the killers themselves; Perry Smith and Dick Hickock. Capote vividly draws the men as flawed individuals who have family, friends and are entirely human. Capote forces us to consider the brutality of the murders alongside Smith and Hickock’s wounded humanity.

In Cold Blood takes a while to get going, with the first chapter a densely descriptive account of the Clutter family’s last day in Holcomb. Although Capote is setting up the precursor of a brutal murder that seemingly has no motive in this sleepy town, the inaugural narrative moves slowly. You wouldn’t be wrong to assume that it does not get much better. But it does. Persevering past the first chapter pays off as we are launched into a remarkably orchestrated cat and mouse chase between the police and the killers. Capote places the reader in the same position as the police who are also in the dark about why the murder took place. While the reader has a slight upper hand in knowing about the existence of Smith and Hickock, we are gripped to see if they will ever manage to connect the dots to a supposedly untraceable crime.

In Cold Blood is such a renowned novel that I do slightly feel that I could not possibly offer any new discussion on it. The novel exists as a meditation on the complexity of human nature, specifically what drives people to murder. Capote’s approach to discussing Smith and Hickock is full of nuance as he interrogates their lives before that fateful day in 1959. He sends us into the childhoods of Hickock and Smith (Smith more-so) in an attempt to paint a more colourful picture of who they were.

While never eliciting sympathy for the men, Capote flawlessly manages to present them as multidimensional human beings, who had their share of unfortunate circumstances and traumatic experiences. We come to understand that the motivations for the Clutter murder are not as straightforward as you would expect. Capote, quite beautifully, manages to meditate on why the distinctions of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ are not as binary as we like to believe them to be. Smith and Hickock were undoubtedly wicked for what they did, but that wickedness does not exist in a vacuum, much like anything else in this world, and Capote speaks to that;

‘Four shotgun blasts that, all told, ended six human lives’ p.5 in In Cold Blood

Many reviewers purport Capote as holding a remarkable level of objectivity throughout the novel, and while I wouldn’t disagree, in the closing pages we become privy to Capote’s opinion on capital punishment. Perhaps it is not surprising to learn that he is opposed to it, because he took the time to humanise Smith and Hickock; they were murderers, but they were also sons. The final pages read as a plea that capital punishment is inhumane, irrelevant of who is in the noose. Capote’s critique of capital punishment, which remains such an infamous feature of the American justice system, poetically comments on the fragility of the American Dream, the utopian idea that was beginning to crumble. In many ways, this discussion of the fragility of the American Dream never falls out of relevance.

I don’t think at any point Capote sensationalises the murders, but In Cold Blood remains, at its core, a creative project rather than a factual account. It is a novel about Smith and Hickock and all that led them to murder, rather than any sort of attempt at memorialising the Clutters. To return to how I opened this review, Capote said he wanted to conduct a literary experiment in prose narrative, and he achieved that experiment remarkably well.5 I would be interested to see how much more vividly the film adaptation paints Smith and Hickock in comparison to the novel (should I watch it?) I would recommend In Cold Blood and call it a borrow!

And that concludes my January Reads! My favourite book of the month was ‘Afterlight’, followed quite closely by ‘Annie John’.

My first read of February is ‘Brotherless Night’ by V.V. Ganeshananthan. I have only just started reading, but I am really loving it - it is living up to it’s prize winning title.

Let me know your thoughts:

❀ What have you read and enjoyed in January?

❃ Have you read any of these books? Would you like to?

❁ Do you have any book recommendations for me based on the themes of this month?

☼ Is anyone else trying to read less in 2025 or is it only those who write newsletters about books that seem to be feeling tired??

Thank you, always, for reading and being here.

See you next month,

Happy Reading! Love Martha

If you know someone who is wanting to expand their reading life in 2025, share this newsletter with them!

Catch up on what you might have missed:

And what I was reading this time last year;

Remember to subscribe if you enjoyed this and want to receive recommendations straight to your inbox!

I endeavour to always introduce you to books that don’t get coverage elsewhere. That is a promise.

But this does feel very unintentionally *of the moment* of me because lots of public readers I know seem to be talking about reading less!! See

’s essay, ’s post and post about how many readers want to read less in 2025. Astrology has to be real for this to be happening to all of us all at the same time. Unless we are all trapped in the same echo chamber instead? (highly possible).https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ida_Vitale - I pulled all my Vitale facts from her Wikipedia page. Even though it was aggressively drummed into us at school that Wikipedia is not a source, it is becoming one of the most consistent places to learn things. I don’t know what this means.

To contextualise this point - in the 1960s, The Netherlands experienced a period of forced adoptions of children born to unmarried mothers. The pregnancies were seen as ‘illegitimate’ (hence why I use the word so repeatedly) and part of a huge ‘social problem’. Over 10,000 women were forced to give up their children during this time - this profile by one woman who experienced that is insightful of just the general atmosphere at the time & attitudes between unwed mothers & pregnancy; https://www.courthousenews.com/distance-mother-sues-dutch-state-for-taking-her-child-away-in-the-1960s/ -

Quote is take from this interview with Capote;

https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/97/12/28/home/capote-interview.html?r=1 - if anyone is at all interested, I thought this NYT interview with Capote about the art of a non-fiction novel and his process in writing In Cold Blood was really interesting!

I like how you describe Independent People as miserable but you liked it lol. Reading Knausgaard right now and there is a bit of the miserable in him too, but I am addicted.

I read In Cold Blood a long time ago and didn't get it, I bet I would feel differently about it now. Glad you found it worthwhile.

I am definitely trying to read less this year. I paid attention to what I found important last year, and I realized I would rather read one deep thought about a book than 10 superficial ones so here we are, going deep!

“better than the bell jar,” well okay

definitely adding afterlight to my hold list!