April Reads

The personal is political; the legacy of colonialism and portraits of women on the brink.

April had two strong themes; the legacy of colonialism and portraits of women who are victims of patriarchal society. Both interrogate that the personal is political and the legal framework and attitudes which govern a country directly shape the lives of those under them.

Without it being planned, four of the novels I read in April (On A Woman’s Madness, Your Little Matter, Co-Wives, Co Widows and Fish Tales) all explored women being subjected to legal and physical manifestations of the patriarchy. We witness them be pushed to the brink of madness because of the way men, and society, treat them. When I reflect on the women in all four of these stories, I think there is sound logic to be found in how they react and respond to the oppression they face.

To see the translated reads from April on Martha’s Map, including authors from Denmark, Suriname, Italy, Central African Republic and Peru, click here.

For those who are new, buy, borrow, bust is my recommendation key: Buy = I loved this book and highly recommend it. Borrow = I liked this book and think it is worth a read. Bust = I wouldn’t recommend this book from my reading experience.

If you even have the slightest desire to read this series, I would not recommend you read this review - it spoils the suspense that so much of the first book relies on. If you’re curious in what the series entails, you can read my review of Vol I (spoiler safe & enticing).

For the few people who have read Vol II, this is for you!

‘On The Calculation of Volume II’ by Solvej Balle

After all that anticipatory build-up, we learn that on day three-hundred-and-sixty-six, Tara continues to wake up on November the eighteenth. She has not managed to escape her time loop by returning to where it all began in an effort to break the cycle. This was an admirable way of thinking, and it is gutting, but perhaps unsurprising, that reasonable logic has not counteracted something which cannot be explained.

Tara begins to chase the seasons around Europe to shatter the monotony of the last year. She seeks a quiet white winter, a budding pregnant spring and a sun-drenched lively summer. The tension that this series so heavily relies upon subsidies quite peacefully here as we contentedly watch Tara find the four seasons in varying parts of Europe. It offers a reprieve from the claustrophobic existentialism that pulses throughout Volume I. Balle meditates on the beauty of cyclical nature; the comforting and necessary predictability that the seasons bring; that winter will end and spring will come. Tara presents as though she is teetering on the brink of madness after living in a suffocating year long autumn; she feverishly yearns for a change of climate. Balle offers both a romantic notion in the use of seasons to measure time and an unsettling one of what life could become for some through the impact of climate change.

Volume II shifts subtly from a meditation on love and marriage to one on consumption. Tara becomes increasingly anxious about what she is taking from the world, painfully evident in the fact that nothing she consume is replenished when the next day, the eighteenth of November, is repeated again. While she has to eat to sustain herself, the nature of her consumption is aggressive as she watches her mark on the world become cancerous as it exponentially grows. She seeks to eat with more variety, but no matter how hard she tries to absorb her impact, humanity's abusive relationship with the natural world is inescapable.

Both Volume I and II deftly meditate on the limits of our humanity in a way that feels liberating rather than suffocating. After reading both, it is becoming increasingly evident that Balle is trying to condemn more than our relationship with time, which is our relationship with life itself. By creating an environment where everyday Tara can see the impact she is having on the world around her, Balle suggests we take more than we can conceptualise from the world. Tara is continuously forced to witness the impact she is having on the food supplies around her. Will Balle take this further in future volumes, and remark on the impact of our consumption beyond food? In stopping the progress of time, Balle has created a universe where the extractive nature of humanity can be analysed on an intimately personal scale; it is unsettlingly thought provoking to read.

The possibility of Tara encountering other people stuck in the time loop never occurred to me, but feels like the perfectly obvious choice for the trajectory of this story. It is tantalising to think about what could be revealed through other loopers' relationship with the planet; Will other loopers be equally horrified about humanity's abusive relationship with the planet, or will something much more sinister take hold? The unpredictability of Tara’s future is unsettlingly addictive. I’m unnerved, for her sake, that this series is composed of seven books.

There is little point in recommending this as a stand alone novel, but I would echo my sentiments from my Volume I review and call this series a buy! I continue to be impressed by On the Calculation of Volume so far and eagerly await for Volume III to be released later this year.

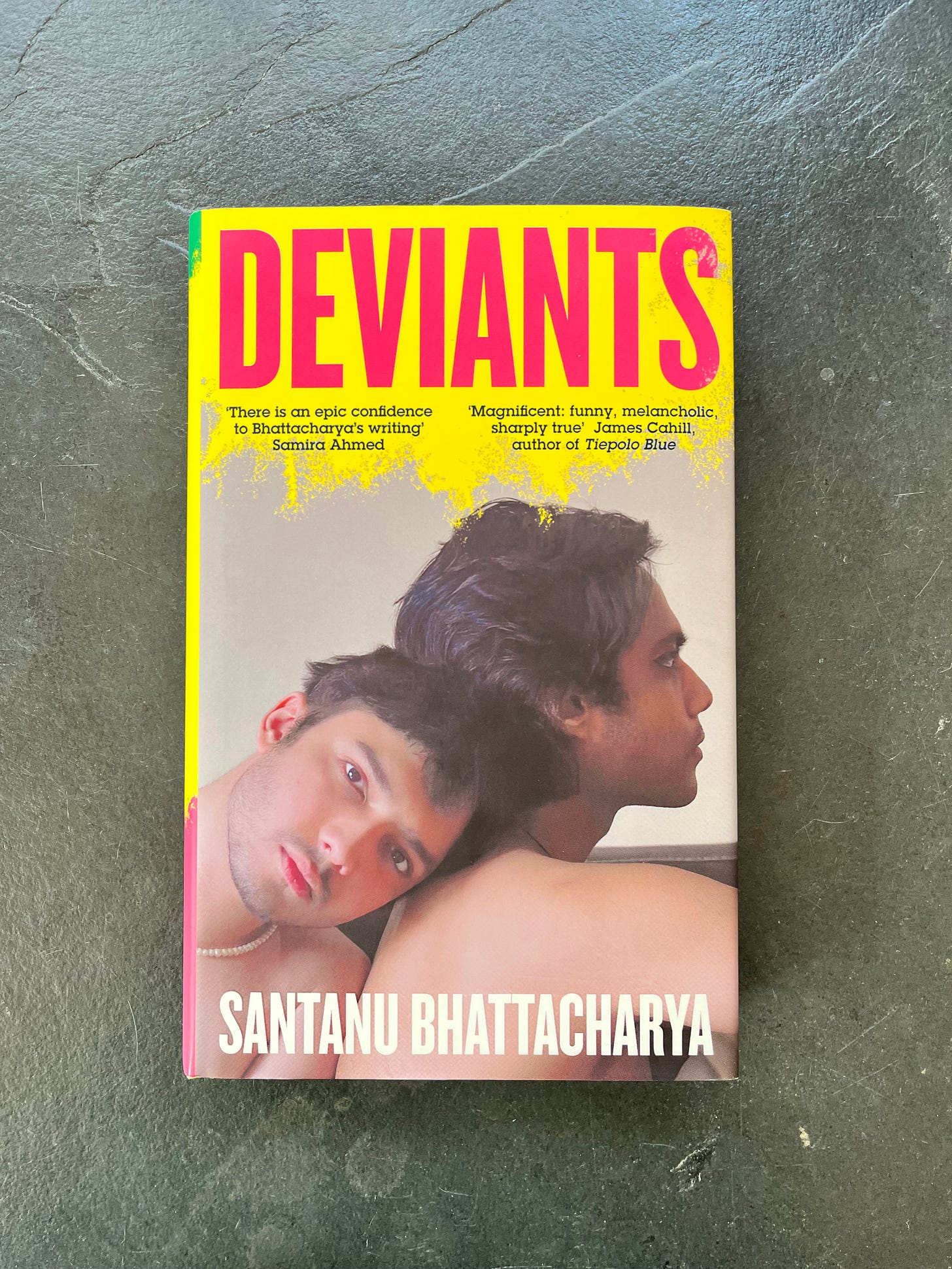

‘Deviants’ by Santanu Bhattacharya

Section 377 refers to a law in the Indian Penal Code (IPC) that criminalised homosexuality. It was part of the IPC which was created in 1860 by the British Empire, that stated that anyone who ‘voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal’ would be punished. For much of the past two-hundred years, it has been illegal to be gay in much of the world thanks to the legacy British of colonialism, which continues to manipulate life in the former colonies. While Britain removed Section 377 in 1967, the law remained in India up until 2018.

Deviants follows three men, from the same family, whose lives mirror significant moments in Indian society's relationship to homosexuality. Vivaan is a teenager in present day India. His parents and peers know he is gay and are supportive of his choices. We follow him openly dating, taking his boyfriend to a school dance and going to (safe) sex parties. While he is surrounded by love in the real world, his life takes a much darker turn when he becomes embroiled in an controversial online relationship.

For Vivaan’s uncle, Mambro, born thirty-years earlier, life looked very different. Mambro’s life changes when he falls in love with his classmate but is unable to pursue the relationship any further. Aged eighteen, Mambro goes to an all boys university and seems to have established a good social status; people like him, they think he’s funny and no one’s said any slurs to him. But as time passes, this status erodes and Mambro finds the walls of the university, in the rural mountains of India, close in on him. It is only after he learns about Section 377 and panics that ‘no one has told [him] about this..’, and the shame he has felt for a lifetime becomes even more suffocating;

‘You realise you’re not only a weirdo, an outcast, a body to rub against; above all these things, you’re a criminal, you’re rightful place is prison’1

But before Mambro, there was his uncle; Sukumar (Vivaan’s Grand-Mamu). Sukumar is hopelessly in love with another young man, but is forced by the social taboos of the 1970s to keep the relationship a secret at all costs. In never being able to live the life he yearns for, Sukumar’s life becomes a derelict landscape of unfulfilled dreams and desires. He painfully watches the man he loves marry a woman and become a father. Despite having his life stolen from him by poisonous colonial laws, Sukumar’s story lives on within his nephew and grand-nephew.

The three narratives initially mirror each other in their first experience of love. Whether it was intentional or not, their first relationships felt indistinguishable. The intensity of a first love is timeless and Bhattacharya encapsulates this universality, each utterly intoxicated with the boys they have fallen in love with. Bhattacharya touches on this innateness in each other them about how they have always known;

‘And even though you’re only a boy of six, and everyone in your world is husband - wife - child, and you’ve never known a man to love another man you feel love for this man, and feel his love reflecting on yourself, as though reaching across ino the mirror, touching your face’ 2

This subtly meditates on the ever-presence of queer love. That it always has, and always will, exist within society. It is timeless despite Vivaan, Mambro and Sukumar’s individual narratives being so distinctly rooted in different decades. Bhattacharya creates euphoric pockets of love for each boy before their narratives become more distinctly rooted in the sociopolitical climates of the time.

Deviants explores how the relics of the British empire live on in India and the soft power Britain still has in shaping the lives of millions of people from almost five thousand miles away. Bhattacharya makes Britain a cornerstone to the narrative, almost a character in itself. Britain is continually comparatively referenced to measure the relative successes or failure of Indian society by those who live within it. While India gained independence in 1947, Bhattacharya presents a lasting colonial legacy that is much harder to liberate from.

Vivaan’s narrative is structured as a voice note, which felt fitting for the present day. Mambro and Sukumar’s are much more traditional, reflecting the cultures they grew up in. We do not get any insight into Sukumar's sex life, and perhaps too much insight about Vivaan’s. Mambro straddles both extremities of each narrative, offering a centre between the two. Occasionally Vivaan’s narrative felt out of place within the others, perhaps intentionally so to reflect the drastic change Mambro has witnessed within his lifetime. While Sukumar and Mambro’s narratives were filled with an uncomfortable amount of pain and suffering, Bhattacharya creates a similar amount of uncomfortability within the freedoms of Vivaan’s life. He questions the uncertainty of the freedoms that exist in our relationships to the online world and the increasingly blurred lines between sex and the internet.

Deviants creates a portrait of a nation that has both changed drastically in such a short period of time, and remains steeped in tradition. While Vivaan has the freedoms his Grand-Mamu could have only dreamed of, the shame he still feels suggests that the wounds from colonialism continue to fester, acknowledging that changing attitudes can take a lifetime, or in this case, in Mambro’s lifetime.

I thought this novel was emotive and heartbreaking. Mambro and Sukumar’s storylines were my favourite, characterised by love and loss that was both painfully relatable and utterly unimaginable. I’d recommend this book and call it a buy!

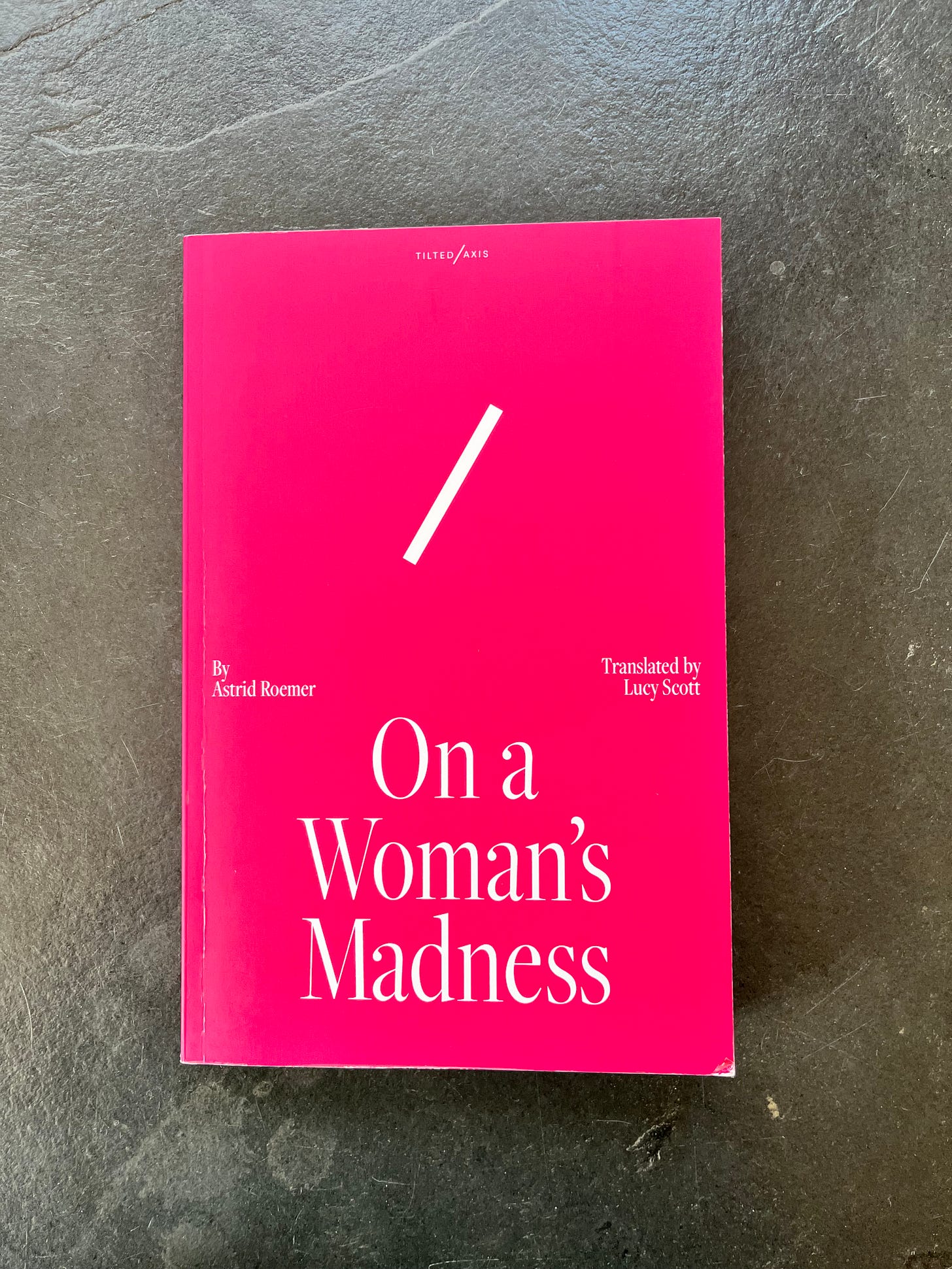

‘On A Woman’s Madness’ by Astrid Roemer

‘I’m a woman, even though I don’t know where being female begins and where it ends, and in the eyes of everyone else, I’m black, and I’m still waiting to discover what that means’3

Noenka has been married to her abusive husband for only nine days when she requests a divorce. Her decision becomes a local scandal and when he refuses, she flees her hometown in Suriname for the capital city, Paramaribo. She is instructed by her boss to return to her husband within thirty-days. Noenka is in search of freedom and the opportunity to forge a new identity, but she cannot escape the societal expectations she unwillingly carries because she is a woman. Her resistance to the bounds of a normative life for a woman results in her being institutionalised, and it is from here that she narrates her story in fragmented episodes.

On A Woman’s Madness is not powered by a coherent plot. With little propulsion, the novel is narrated in what I could only describe as a dream-like flow state. There is an immense amount of friction for the reader in trying to piece together the story as it restlessly circulates on exchanges that feel inconsequential. Once you reach a moment of clarity where you can discern what’s going on, you don’t want to stop reading. Roemer’s beautifully profound prose combined with a narrative that is chaotic creates a novel that is both understandable, and illogical. Perhaps Roemer chose to construct the novel this way to reflect the state of mind of a woman who is being accused of being mad. But the only madness Noenka sees is the social and political institutions that wish to determine life is lived in a certain way.

Noenka’s identity pushes against the expectations of womanhood; she is rejecting her husband, she has no children and she embarks on an affair with a woman who has two disabled children. Noenka internalises no shame about who she is, who she loves or who she wants to be. It is her defiance against society that articulates this sense of freedom she seeks, but not as a place, as an activity.4 This specific sense of freedom that Noenka internalises resembles a rejection of the history of Suriname, an antithesis of all that the country endured for hundreds of years. Europeans arrived in Suriname and was colonised and enslaved for over four-hundred years. While independence was eventually gained 1974, the roots of colonialism remained.

Noenka was brought up in a Suriname that was ‘free’, but this freedom does not extend to society's expectations of her. Arguably, Roemer is meditating that the country may be free, but she, as a woman, is not. For Noenka, there are no freedoms because she is expected to behave and conduct her life in a certain, heteronormative way, and that is what she is so compelled to resist.

I would not want anyone to be under any illusions that this story is easy to understand, because it is not. I read this alongside

and and we were enamoured and confused in equal measure. This confusion made for some brilliant conversations about the freedom and constraints of a narrative and I would be inclined to say that the group chat made my reading experience of this novel infinitely better. The more distance I have had from On A Woman’s Madness, the more I admire it. While it was not easy to follow, it was easy to understand how Noenka was feeling. You can feel her suffocation as she desperately seeks safety and meaning outside of how society wants her to perform. It suggests that within a patriarchal and postcolonial society, this is a safety she might never find.I would recommend this book for fans of Toni Morrison (there is a similar energy) and if anyone is looking for a challenging novel to read with a friend (because I think reading this alone could send you mad, perhaps as Roemer intends). I would call this a borrow!

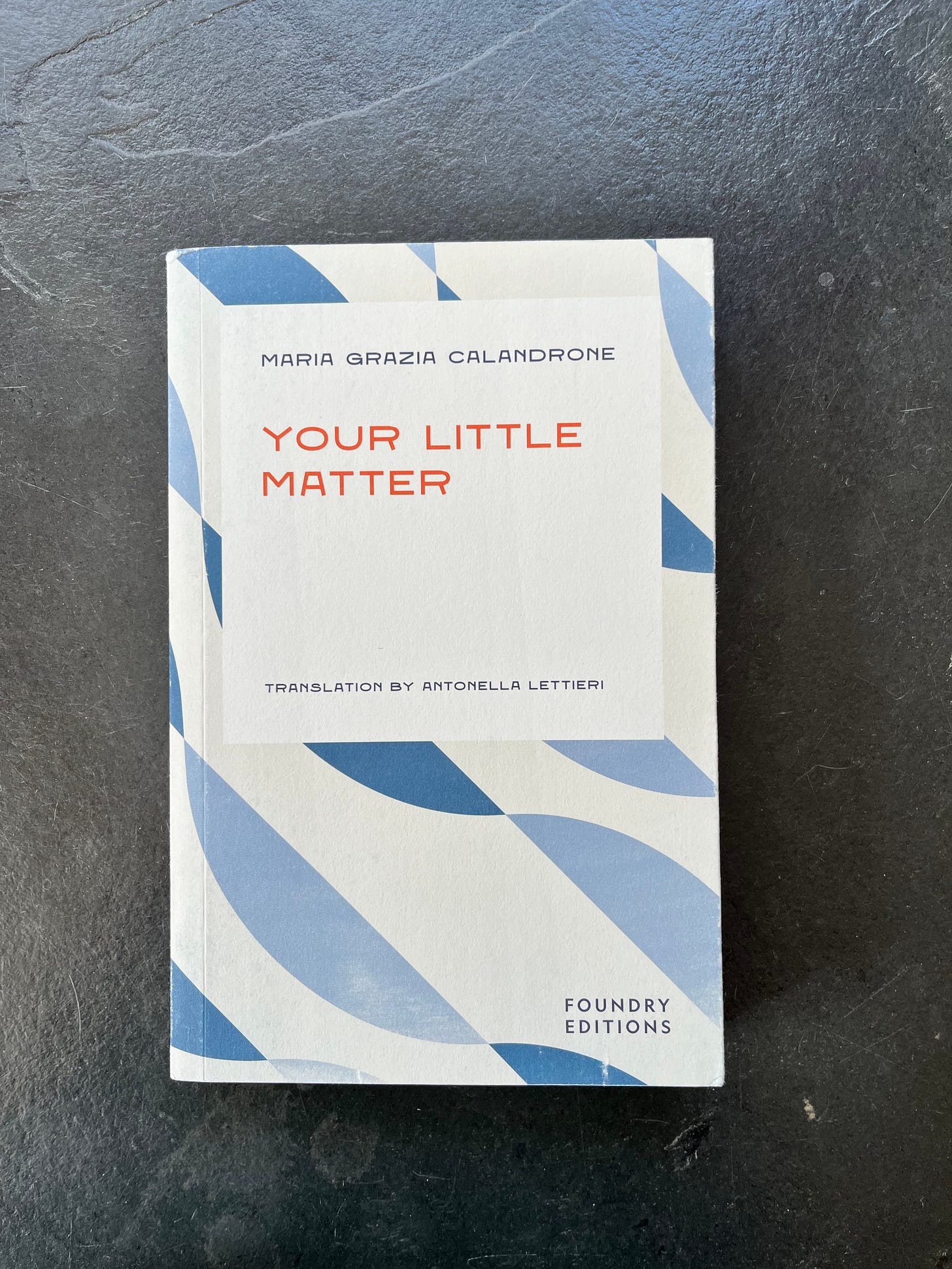

‘Your Little Matter’ by Maria Grazia Calandrone

A little eight-month-old girl is abandoned on the lawn in the Villa Borghese in Rome, 1965. The little girl is Maria Grazia Calandrone, and her story made national news. It triggered a major police enquiry which framed Calandrone’s mother as a criminal. Calandrone was adopted by Giacomo Calandrone, the leader of the Italian Communist Party, and his wife and lived a happy life. When Calandrone wrote a memoir about her relationship with her adoptive mother, she was invited to present her memoir on TV. After her segment, Calandrone started to receive messages from people saying they believed she was Lucia’s daughter. Until this moment, Calandrone knew nothing about her biological mother and why she abandoned her at only eight-months-old.

Your Little Matter retraces Lucia’s life out of a desire to set the record straight and understand who her parents were. Calandrone discovers that there was hardly a transformative tragedy which led to her abandonment. Instead, Lucia was arguably destined for a challenging life from the moment she was born. Thus, Your Little Matter is a study of the sociopolitical landscape of Southern Italy from the 1950-60s and paints a portrait of hardship, characterised by a restrictive religious and political landscape.

Lucia was born to a poor, farming family in the countryside in Palata. Due to her gender and the socioeconomic environment, Lucia has no hand in her fate. She is married off by her father to the village ‘idiot’ who is twice her age. It would be cruel of me to detail anymore of the events of Lucia’s life, because learning about her alongside Calandrone is the beauty of this novel. It is fascinating to witness Calandrone learn about her parents retrospectively, uncovering a whole history about her ancestors she was unaware of for over fifty-years. To be intentionally vague, Your Little Matter interrogates the economic hardships in the South that led to the mass migration of workers to the North. Calandrone analyses the tragic institutional failures and misogyny that ultimately led to Lucia’s fate.

‘This is not what we were dreaming of.. The sigh crosses the length of history, is spoken in every language and every dialect of the world with the same pain, the same anger, the same resignation, as if we all were the same person’ 5

The ambition for what Calandrone wants Your Little Matter to be is touching, and the story is propulsive - until the second half, where it becomes tiresome. Once it is revealed what happened to Lucia, Calandrone meditates on the utmost of possibilities that could have lead to Lucia’s fate. It is understandable that Calandrone wants to revisit again and again what happened, to disprove all the allegations that imply Lucia is a criminal. As her daughter, it is logical that Calandrone wants to set the record straight about her biological mother. But as a reader, this section was veering on painful to read.

While perhaps not evident at the time, it is evident to a modern reader the motivations of Lucia abandoning her daughter, and subsequently what takes place next. However, Calandrone appears to be writing to a specific audience; to those who watched her mother be sensationalised by the news in the 1960s. She combs through all the theories that were proposed and methodically disproves each one. Perhaps this was cathartic for Calandrone, but for the reader, it felt increasingly unnecessary. Ultimately, it was a shame for the novel to end on this note because up until the second half, I was completely engrossed on how fascinating the concept and execution of this novel was.

I would recommend this if you enjoy novels that explore the hardships faced by women because of social and legal misogyny. Your Little Matter tells a beautiful story, and while I wish narratively Calandrone gave the novel a different form, I think the tale of Lucia is one worth reading - so much has changed between her lifetime and ours. I would call this a borrow. If you are interested in this story but don’t want to read the book, may I suggest you read this article instead! It is, in essence, a condensed version.

‘Co-Wives, Co-Widows’ by Adrienne Yabouza

Ndongo Passy and Grekpoubou are the co-wives of successful businessman Lidou. The novel opens with Ndongo Passy and Grekpoubou getting ready to exercise their right to vote for the first time on election day. The line is twenty-five meters long, as women across Bangui have come out in their hundreds to vote. They wait for hours in the merciless heat, ready to ‘[savour] the sense of importance of sliding [their] ballot paper into the box, despite the looks from the officials’.6 Lidou is disinterested in voting and seems genuinely taken aback by his wives fervour in wanting to be ‘good citizens’. However, he allows them to choose to do this for themselves, despite counteracting that freedom almost immediately by reflecting on them as his ‘possessions’.

What concerns Lidou more was his impotence. Stressed about his reality of having to satisfy two women, Lidou takes a trip to the chemist to seek a remedy to help him in his inability to perform. The day after he takes his first dose, he suddenly drops dead. In the wake of his death, Lidou’s cousin Zouaboua accuses the women of poisoning their husband to ensure he inherits Lidou’s wealth and property empire, instead of the wives. Both women have substantial influence; they run their home and are respected across the community. Just as they acquire democratic rights, they suffer a misogynistic smear campaign framing them as witches to omit them from their inheritance. Faced with no option but to flee their home, Zouaboua believes he has left the women desolate, but Ndongo Passy and Grekpoubou want to fight for what is rightfully theirs.

Co-Wives, Co-Widows creates a window into a society that is both traditional and progressive. It opens with this elation from Ndongo Passy and Grekpoubou in their opportunity to exercise their rights, a belief that their voice is becoming more valued in the society they live in. Only to realise that the legislative change does not necessarily trickle down into societal attitudes - when they need their rights to be upheld, they are stranded and left with nothing. Yabouza alludes to a tension within the Republic, of wanting both progressive and traditional cultures to coexist within society. The novel comments on the corruption, misogyny and an unjust legal system in the Republic, where bribery is seemingly a characteristic cornerstone of society. The resilience of the wives suggests they are accustomed to being treated like second class citizens, but they are not necessarily comfortable with it. Yabouza handles these themes with care, signalling that polygamy in African contexts is complex and while it can be appropriate to critique, it is not the imitation of evil.

What Yabouza anticipates from the reader is perhaps an expectation that Ndongo Passy and Grekpoubou would be pitted against each other, because they are two women in a polygamous relationship. There is hate within this novel, but it is not directed at any women. Instead, it is reserved for the men that believe it is within their right to be violent and misogynistic to any woman. Between the women, there exists this heartwarming and supportive friendship. Their companionship is lovely to read and Co-Wives, Co-Widows emerges into this fable of goodwill and social justice; that if you treat people well, you will be rewarded.

Yabouza’s prose is quick and charming, demonstrated in lines like ‘The sun, like the mosquito, was pan-sexual and gregarious; every variety of flesh was welcome’. 7 Co-Wives, Co-Widows was a pleasure to read. I thoroughly enjoyed the duality of the story being both lighthearted in mocking Lidou and full of social commentary about women's rights in the Central African Republic. I would enormously recommend this book and call it a buy! It was a joyful and absorbing read.

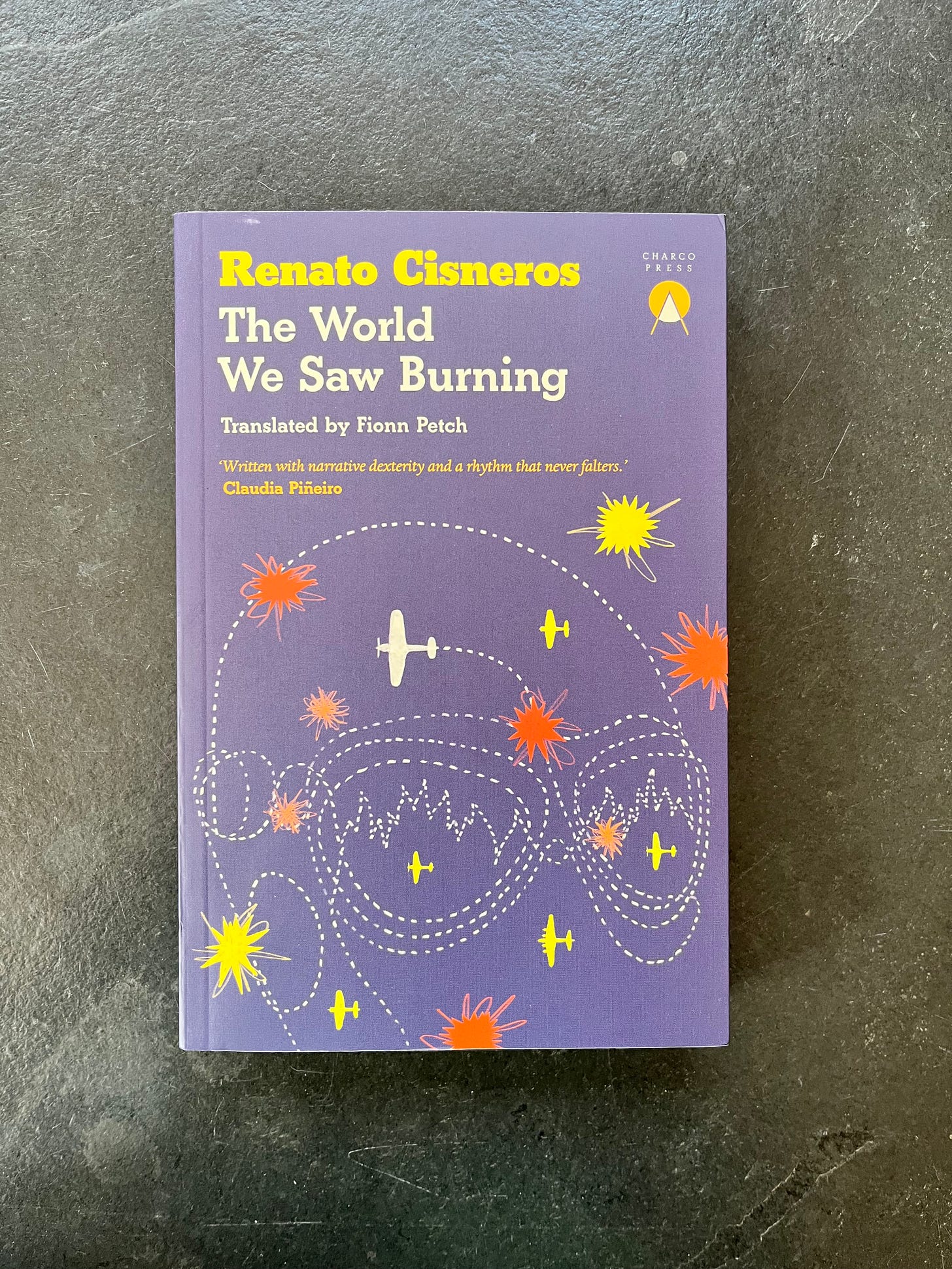

‘The World We Saw Burning’ by Renato Cisneros

A Peruvian journalist, who lives in Madrid, is getting a divorce from his wife, Erika. After packing up and leaving their apartment, he catches a taxi to take him across the city to his new home. Whether it is fate, or just bad luck, he gets stuck in the back of the taxi because of bad traffic. He begins talking to the driver, Antonio, who is also Peruvian, about the concept of home. Antonio begins to tell him a story; about a boy with an Italian father and German mother, named Matías Roeder, who leaves Peru in 1939 to go to New York with the ambition of never returning. His dream of travelling the world leads him to join the US Air Force and become a bomber in the second World War. However, his naivety and ambition come crashing down when he discovers his next mission is to bomb Hamburg, where his mother’s family live. Antonio recounts all of this to his passenger, who is captivated in the backseat as he transitions from one era of his life to the next.

The World We Saw Burning is a story of migration and seeking something better elsewhere. It explores that the demands of exile and the desire to move are as old as time. It confronts the interconnectedness of humanity, the inevitability of suffering within our lives and the search for identity. These concepts are immensely profound, and arguably, too vast for this book. While Cisneros' prose is beautifully evocative, the two narratives never quite click.

The narratives do not move together, but at completely different rhythms. They felt so disparate; operating as brilliant storylines on their own, but together creating something disjointed. While the journalist narrative was initially compelling, Matías storyline increases in such magnitude it swallows it up. Perhaps Cisneros brought these narratives together to comment on the cyclical nature of humanity. That beneath different lives, there is profound commonality to be found in our hopes, desires and fears. In theory, this works.

Nothing could be more different than the lives of Matías and the journalist. But despite both narratives being full of grief and intimate explorations of what home means, there is too much conflict between them on the page. The World We Saw Burning could have been a profound exploration on the issues of emigration facing Peru, with one in ten Peruvians living abroad due to economic and political instability at home. This is alluded to within the novel when the journalist chastised for commenting on the Peruvian elections from far Madrid; ‘No one likes you in Peru, in Spain nobody knows you!’. Antonio and the journalist both discuss the political instability in Peru, equally relieved and saddened they left.

Though political instability plays a significant role in Matías’ life, the recounting of devastation of the Hamburg bombing in 1943 eclipsed the discussion of political instability in Peru to one of the depravity of humanity. It rendered the journalist's narrative insignificant, and while this could have been intentional, it didn’t feel as though it was. This variation of intensity created a chasm that kept growing throughout the novel and became jarring to read.

I simultaneously liked, and didn’t like The World We Saw Burning, so I would call it a borrow. It is a worthwhile read for the storylines individually. Anyone who enjoys the exploration of World War or aerial warfare in their fiction would like this.

‘Portrait of an Island on Fire’ by Ariel Saramandi

Mauritius is often known as a holiday destination and a tax haven for the ultra-rich; an idyllic paradise with picture perfect beaches and lavish hotels. But this romanticised image is not the reality for most Maritituans living there.

Portrait of an Island on Fire is a searing collection from Saramandi about the issues of contemporary Mauritian society. Saramandi interrogates the lasting social and political effects of colonialism on policy, healthcare, education and environmental issues. She chronicles the unique intersections of race, class, gender and language that characterise Mauritius within its particular forms of patriarchy and white supremacy. Threading her own experiences with the history of the island, Saramandi paints a portrait of an island that is on fire.

I will be interviewing Saramandi imminently about Portrait of an Island on Fire for ‘Martha’s Monthly’ - more on this soon!

This collection is courageous and heartbreaking. I loved it and think you will too. For now I will say this is a buy - it is outstanding!

‘Fish Tales’ by Nettie Jones

On first impressions, Lewis Jones leads a hedonistic life, but there is something much more sinister at play underneath. We initially meet Lewis as an adolescent where she is being sexually abused by her teacher; ‘Jesus Christ, he has been fuckin’ me around since I was twelve. I wasn’t even paying full fare at the movies when he molested me’. 8 Continually exploited by those around her, Lewis ends up marrying Woody; a deeply suspicious character who is exceedingly wealthy. Lewis’s life is funded and dictated by Woody, and the reader is put in a position of voyeurism as we witness Lewis continuously engage in taking drugs, drinking alcohol and orgies.

The narrative is hazy as one man bleeds into the next and we watch Lewis’s vulnerability grow; ‘Let her take it against her will’ he suggested, ‘I’m always taken that way, creep’ I blurted’.9 What becomes increasingly evident is Lewis is rarely the architect of her life. Lewis is malleable to the men around her; never in control and there to be used. She becomes a currency, her value inherently linked to her sexual performance. As the novel progresses, it becomes increasingly evident that Fish Tales is the portrait of a woman going insane at the hands of men.

This hedonism changes when she meets Brook, a quadriplegic. Lewis' appetite for control and her desire to be valued, and witnessed, finds its home in Brook. His inability to physically dominate her is mesmerising for Lewis. She immediately slips into the role of a career, insatiable to the idea that he needs her. Lewis finds herself untethered from physical sexism she is so familiar with, and subsequently untethered from reality.

Originally published in 1985, critics received Fish Tales as ‘assaultive’ and ‘pornographic’ which isn't entirely untrue. Fish Tales is an onslaught on the senses, with every chapter named after whoever Lewis is involved with. There are some glimmers of sensitivity, with the dominant theme one of abuse. At a glance, Jones has written a story about the sex filled life of a ‘party girl’ in 1970s New York City. But any reader with an ounce of insight can decipher that Jones has written a tale of victimisation, of vulnerable women at the hands of manipulative and violent men. While we are never made privy to Lewis’ childhood before the abuse she is subjected to by her teacher, we are made privy to Lewis' deteriorating psyche as the novel progresses. Thus, it is implied that Lewis’ mental state is directly shaped by the misogynistic abuse she had been a victim to since she was only a child.

Though the complexity of this story and the richness of its characters is entrancing, Fish Tales is anything but a smooth ride. Perhaps best articulated by Jones who said; ‘I wrote Fish Tales as it came to me through my senses’, this emotional impulsivity is glaring throughout the narrative. A sense driven story is what Jones delivers, but arguably in prioritising the senses, Fish Tales loses its ability to captivate beyond its shock factor. While Lewis’ sexual life is almost always described in great detail, the landscape of anything beyond that is not. Without the prologue, which recounts the scene of a naked woman talking to herself and masturbating on the street, it would be admissible for the reader to not fully comprehend the trajectory of the narrative beyond Lewis’s escapades.

An early review of Fish Tales said;

‘Unredeemed by compassion, the brutality in the novel is assaultive; it also forces the reader into the role of voyeur. Blurring the boundaries between the literary and the pornographic, the prose generates a great deal of power but it is not effectively contained.’ Carolyn Gasier, 1984 in NYT

While I would contest Gasier’s initial point that Fish Tales is unredeemed by compassion, because there is some, I would echo her stance that the prose is powerful but not effectively contained. The energy of this novel outshines the technicality of its structure and thrust, but I did not mind it. The obscurity of the narrative makes for a novel that is as entertaining as it is confusing. The grotesque and immoral nature of Jone’s characters are captivating in their abhorrence. Toni Morrison was the editor of Fish Tales and if you like her work, I would recommend this! I could feel her hand all over the novel in a way that felt very familiar. I would call this a borrow!

And that concludes my April Reads! My favourite reads of the month were ‘Co-Wives, Co-Widows’ and ‘Portrait of an Island on Fire’.

My first reads for May are ‘Solenoid’ by Mircea Cǎrtǎrescu, which I am reading with

and ‘Yonnondio’ by Tillie Olsen, which I am reading with and the Closely Reading book club. I never read two books at once so this is unheard of, but I can report that I am just about coping.Let me know your thoughts:

❀ What have you read and enjoyed in April?

❃ Have you read any of these books? Would you like to?

❁ Do you have any book recommendations for me based on the themes of this month?

☀︎Now it is the beginning of May, I think it is safe to say we’re well into 2025! I want to know: What’s the best book you’re read so far this year?

Thank you, as always, for reading!

See you next month,

Happy Reading! Love Martha

If you enjoyed this newsletter, why not share it with a friend or someone you’d like to impress with your impeccable taste <3

Catch up on what you might have missed:

My interview with Saou Ichikawa, author of ‘Hunchback’ in ‘Books + Bits’ with

And what I was reading this time last year:

Remember to subscribe if you enjoyed this and want to receive recommendations straight to your inbox!

I endeavour to always introduce you to books that don’t get coverage elsewhere - that is a promise.

Deviants, p.157

Deviants, p.1

Quote found from p.184 in ‘On A Woman’s Madness’ by Roemer

The comment about freedom as an activity not a place is taken from this quote by critic Nicholas Rinehart; "In On a Woman’s Madness, freedom is not a place but an activity, a kind of restlessness that never settles into safety but still insists upon the necessity of its seeking," in this review.

Your Little Matter, p.183

‘Co-Wives, Co-Widows’, page 15

‘Co-Wives, Co-Widows’, page 11

‘Fish Tales’, p.20

‘Fish Tales’, p.207

I believe books three and four of On the Calculation of Volume are being released in English simultaneously! (tbh I'll probably pre-order them both at the same time...) And: the added pleasure of reading a review of something I *have* read is that you always articulate a theme I felt but couldn't put into words. Very intrigued to see these ideas play out.

Looking forward to reading your next author interview (!) and now to see if I can track down Co-wives, Co-widows--"joyful and absorbing" sounds like good tonal shift for my reading.

Interested to hear your thoughts on the newest Renato Cisneros book. I read The Distance Between Us a couple years ago and really really enjoyed (although that one is based on his own father and his political career in Peru so the scope was narrower than that of his latest work, from your telling). I think I would still pick this up with guarded expectations perhaps.

I also had a month that dealt with colonialism. I read Short War by Lily Meyer which addresses the coup in Chile ending Allende’s government and the ripple effects of that on a small cast of characters. I also read Beasts of a Little Land following a group of characters in Japan-occupied Korea during the early 1900’s into the WW2 years. I think this book does live in Pachinko’s shadow a little bit, and while I liked it, I didn’t like it as much as Pachinko. But I still find the Japan/Korea relationship very interesting and appreciate exploring that via literature.

I also finished Octavia Butler’s duology with The Parable of the Talents. It was a bleak read at times, felt a little too relevant to the current moment in the US with the rise of the religious right, and also featured a very unlikable narrative to me! An interesting reading experience all around and I wish I had more people to discuss with.