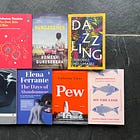

Welcome to Martha’s Monthly, March Reads edition! The theme this month was desire; specifically, who gets to have it. The relationship between desire and inequality in several novels made me think about the luxury of trying again, of being able to fail and not fall through the cracks of society, to have the privilege of being caught.

To see the translated reads from March on Martha’s Map, including authors from Chile, Mexico, Egypt, Norway, Croatia, France, Argentina, Spain and Denmark, click here.

For those who are new, buy, borrow, bust is my recommendation key: Buy = I loved this book and highly recommend it. Borrow = I liked this book and think it is worth a read. Bust = I wouldn’t recommend this book from my reading experience.

‘The Savage Detectives’ by Roberto Bolaño

Last year, The New York Times shared their controversially titled ‘100 Best Books of the 21st Century’. Despite the many criticisms I have of this list, I made note of the translated novels on there which I had not read. The Savage Detectives had come up on my radar a few times before and now that it was officially the thirty-eighth best book of the twenty-first-century, how could I not read it?!1 Critics have showered Bolaño in praise for decades; he has been called a genius, that The Savage Detectives is a masterpiece Daniel Alarcón said changed his life. All this considered, it is fair to say my expectations of the novel were very high, creating quite a cliff for it to fall off when I realised I did not like it.

The Savage Detectives spans two decades, crosses multiple continents and has fifty four narrators. This sprawling story starts in Mexico City 1975, with seventeen-year-old Juan García Madero as our first narrator, in the form of diary entries. It is through García Madero that we learn about the elusive ‘Visceral Realists’, a self proclaimed group of literary gorillas led by poets Arturo Belano and Ulises Lima. With a love of drinking, sex and poetry, García Madero envelopes us into the bizarre life of the visceral realists leading up to New Years Eve 1975, when Belano and Lima leave the city in pursuit of an adventure. They are on the hunt for Cesárea Tinajero, a 1920s poet whose work is revered but she is nowhere to be found.

Here is where the book alters from a dairy style narrative to four-hundred pages of first person interviews, spanning from 1976-96, from those who have interacted with Belano and Lima. They range from friends, enemies and strangers as Bolaño takes the reader on a wild goose chase across the globe as we become the detectives and try to piece together what Belano and Lima have been doing since they disappeared on New Year's Eve 1975.

Belano and Lima spend over twenty years embroiled in crime, taking drugs and unable to stay in a job, or a country, for longer than a few months. Initially, there is something intriguing about trying to piece together someone's life from outside perspectives. There were some recurring narrators who I became fond of, looking forward to their perspective and hearing where life took them. However, around the twentieth narrator, momentum is lost. The narrators lose their charm and the focus on understanding what happened to Belano and Lima fades increasingly into the background. The Savage Detectives becomes a compendium of humanity from around the world. This challenges the thrust of the novel which is, in essence, chasing two fools around the world who seemingly care deeply about poetry but do little in pursuit of this. They become enigmas, omnipresent yet elusive, embodying the novel's essence through their growing obscurity.

This book is admirable on a technical level. The structure and style of The Savage Detectives is remarkably clever. It is inspiring to read Bolaño tell a story through everyone else's point of view. It is an innovative concept for a novel. But the experience of reading it? There was nothing to tether me to the story as I drifted from one narrator to the next. The number of narrators creates an apathy about Belano and Lima, weighted down by the confusing and incoherent trajectory of their escapades. Once I became apathetic about the central figures of the story, the book became tedious. Several narrators barely mentioned Belano and Lima, instead embarked on lengthy stories about their own personal lives. When I started coming across these narrations, which felt self-indulgent and pointless, I felt like The Savage Detectives had entirely lost its grip and turned into something I barely recognised.

Bolaño puts the reader in the position to become the detective; piecing together fleeting glimpses to create an emerging picture of the events that took place after New Years Eve 1975. In theory, this creates a highly engaging story, but in practice, it was tiresome. The narrative inconsistencies of the novel became weary. While each voice is unique and well crafted, the sheer volume of them sacrifices the momentum that a novel of this nature so desperately relies on. While I appreciate that The Savage Detectives aims to comment on the philosophy idealism and the futility of trying to know someone, I argue that instead it paints a picture of humanity which is exceedingly dull. Perhaps a core tenant of enjoying The Savage Detectives is a love for poetry. Or, perhaps, The Savage Detectives is overwritten and overrated.

I kept pushing to understand this novel because of its reputation. When you don’t like a book that is this revered, it can feel like the whole world is seeing something you're missing. To an extent, I still feel this way.2 I would not recommend The Savage Detectives, this is a bust! However, I will not rule out Bolaño yet. I am open to trying him again, perhaps with By Night In Chile? I do want to read 2666, but I am now unsure if this is a wise ambition? I know I have readers who loved this, and I’m happy for you - I wish that I did. My expectations definitely affected my experience with this novel, but that aside, I am not sure I was ever going to enjoy having fifty four narrators.

‘The Accidentals’ by Guadalupe Nettel is a collection of short stories about family and relationships. It interrogates the dynamics of family life; the secrets, yearnings and devastation that encompass it. This is what Nettel does so seamlessly in ‘Still Born’, and again in this collection.

The Accidentals opens with this quote from Anais Nin;

‘We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are’

Which succinctly encapsulates the tone of these stories. This is a guiding light for the collection, interrogating how our understanding of anything is merely just a reflection of ourselves. The protagonists of these eight stories find the ordinary courses of their lives disrupted by an unexpected event and are pushed into an unfamiliar environment. They react not based on objectivity, but how they are feeling. The Accidentals follows a variety of lives which are all rooted in our uniquely human condition of being unable to separate our emotions from actuality.

Nettel interrogates this idea of waiting for life to ‘start’; that it is happening elsewhere and not to you, that the grass is greener on the other side. Every story is deft and emotive, vivid in characterisation and concept. Nettel writes with such piercing accuracy, reading her work is like looking into a mirror. She delivers lines that make you catch your breath because it seems she is speaking directly to you about the conflict of the human condition;

‘Rarely do we decide how we should act based on the present, and much less on the intuition of the moment, We do it based on the good or bad experiences that we have had before, and on the prejudices about reality that we form as a consequence of these’ - p.32 in The Accidentals

The final story in the collection, ‘The Torpor’, is about a futuristic, post-covid world that felt fantastical and eerily familiar. She meditates on the trajectory of our society since the pandemic, the impact it has had on our humanity, and our relationships. Nettle encapsulates an alarmingly familiar erosion of our community and connection in the face of technology. Moving between the soberingly real and the imaginative, the collection presents a portrait of humanity; all that we think we will be, compared to all that we are. Nettel ruminates on how we see ourselves and how we see others as she weaves together comforting and unsettling tales about the human condition.

‘Childhood does not end in one fell swoop, as we wished it would when we were children. It lingers, crouching silently in our adult, then wizened bodies, until one day, many years later, when we think that the heavy burden of bitterness and despair we’ve been shouldering has turned us irredeemably into adults, it reappears with the force and speed of a lightning bolt, wounding us with its freshness, its innocence, its unerring dose of naivety, but most of all with the certainty that this really and truly is the last glimpse we shall have of it’ p.97 in The Accidentals

Short story collections often have inconsistencies, where some stories explicitly outshine others, but that is not that case here. I often don’t enjoy short story collections, but Nettel’s writing is consistently thoughtful and perceptive. I have not read a collection this strong since ‘Every Drop Is A Man’s Nightmare’ in 2023! Nettel’s stories were a pleasure to get lost in, full of rich expansive lives in such few pages, she is an incredibly impressive writer. I would absolutely recommend this collection and call it a buy! Nettel’s prose is brilliant, suffused with such sharp poignancy. If you have never read any of her work before, I would unequivocally encourage you to do so.

‘On The Greenwich Line’ by Shady Lewis

In East London, an unnamed local government employee spends his days trying to figure out what latest policy announcements mean for himself and the migrants he works with. Working in the housing office is a bureaucratic nightmare; they are being crippled by austerity and have extremely limited funding. As a favour to a friend, he offers to organise the funeral of Ghiyath, a young Syrian refugee. Ghiyath’s body is in the UK, but his family cannot get to him to hold a funeral for their son. When our protagonist's life collides with Ghiyath’s death, he is confronted with just how much he has in common with those who fall through the cracks of society.

On The Greenwich Line portrays life amid contemporary Britain’s austerity and its impact on individuals. Our protagonist, who migrated from Egypt, gives personal and professional insight into the migrant experience in Britain. He meditates on the experiences in his childhood that made him leave Egypt and come to the UK to seek a better life, similar to the dream-like prose found in Hisham Matar’s My Friends. After settling and getting a job in the government, his Uncle can’t believe how lucky he has been; ‘You have your own chair! A chair for you to sit on!’.3 In so few words, this conversation sheds light on the impossible challenges and insecurity migrants face in carving out a place in society for themselves.

For him to have a chair, a place you can rightfully belong, where people can find you, is monumental. His Uncle’s shock in his good fortune suggests how lucky he has been, which feels ironic considering the nature of his job and the loneliness he experiences. When he is crippling under the weight of it all, he remembers that ‘I have a chair’, something that is his.

Lewis is Egyptian but has lived in Britain for years working for the NHS and in government, and he encapsulates British humour remarkably. The tragedy in this novel is interlaced with dry wit and on the nose humour about the immense challenges social workers face in just trying to perform their job. It is shocking almost to the point of disbelief, and while this story is fiction, it is rooted in reality.

Lewis explores the relics of the British Empire and myths that power the imagery of the UK around the world, versus the reality of life here. He and his co-worker, who also migrated to Britain, share some of the first places they were excited to see; speakers corner and the meridian line at Greenwich observatory. Both exchange their feverish anticipation for these sites, only to feel disappointed when they arrive. Lewis addresses the irony with these two characters, who can identify with the migrants they work with on a daily basis, but are faced with the reality of having to refuse help because they don’t have the funding. They are watching people like them die at the hands of systematic failures and are unable to do anything about it. Lewis skilfully intertwines these two opposing narratives, unveiling how Britain today is in direct conflict with the myths of the past which continue to power the perception of Britain. He does this subtly, but with immense precision, demonstrating how many people come to this country believing they will be saved, only for them to fall through the cracks and disappear.

On The Greenwich Line is honest in its nature, frank and unwavering in its criticism of the social systems and culture in Britain. It tenderly addresses the hardship and isolation that comes with social integration as a migrant. This novel is brilliant and I would call it a buy! I would recommend this book to anyone who is interested in reading about austerity in Britain and exploring the theme of emotional home versus physical home.

‘Back in the Day’ by Oliver Lovrenski

Ivor and Marco have been best friends for years. They started getting high when they were thirteen, dealing when they were fourteen and carrying knives when they were fifteen. Now aged sixteen, their lives are hurtling towards instability as they edge closer to slipping through the cracks of society. Back in the Day is a tragic love story of the friendship between a group of teenage boys who have no one else to turn to. It’s about hope and growing up too fast.

Narrated in lyrical verses and vignettes, Lovrenski gives us glimpses into a trajectory of tragedy for these young boys. Through a variety of reasons that are not their fault; absent parents, a failing school system and inadequate social services, the boys are unmoored. Idle and bored, they find themselves taking drugs and becoming familiar with the streets. Despite the disjointed narrative, Back in the Day manages to be emotive. We simultaneously hear about their hopes of stability and success while we watch them become more entangled in a life on the streets. It is not clear for the reader, until it is too late, when the substance use transitions from recreational to addiction for the boys.

‘It wasn’t dreams we was lacking but hope’ p.15 in Back in the Day

Lovrenski masterfully encompasses teenage heartbreak and misplaced desire throughout the novel. This novel could be described as ‘coming-of-age’, but that doesn’t encapsulate the pressing nature of this tale. Back in the Day is of its time, discussing issues which are so relevant to the youth of today. Lovrenski is not moralist in his portrayal of the boys, instead leading with heart in his vulnerable tale of young men. While set in Oslo, the themes explored within the novel are universal. Lovrenski explores the role of social media in making drugs more accessible and prolific and the role of snapchat in drug dealing. There is continual recognition in Lovrenski’s tender prose that there are a myriad of reasons as to why the boys are in the position they are in. While the activities that Ivor and Marco are engaging in are deeply adult, Lovrenski constantly reminds us that they are just children.

‘I was young when I started carrying a blade, fourteen maybe thirteen, not gonna lie, to begin with no one needed it either, we was mostly playing hard’ -p.61 in Back in the Day

Back in the Day is simultaneously serious and comedic in its approach, weaving the reality of addiction with the silliness of teenage boys. The story pulses with love, despite the devastating nature. The prose is full of slang and references to culture which root it in the modern day, but the youthful ambition and yearning for safety feels timeless. This novel is propelled by emotion with verses filled with love, naivety and danger as they search for purpose in a world that has disregarded them. We are painfully enveloped in their desires as we watch them lead a life that is taking them in the opposite direction. They’ve grown up too fast, but they’re still too young to understand.

Occasionally I wanted more from this novel; more characterisation, dialogue and insight into the world of Ivor and Marco. I appreciate why Lovrenski chose the narrative style he did to handle these themes, but when books like Young Mungo and Close To Home handle similar distress in such unflinchingly intimate prose, I couldn’t help but want more connection to the story. Nevertheless, Back in the Day is a compelling novel that I would argue any adolescence should read. I’d call this a borrow. This novel is Lovrenski’s debut aged only twenty-one, which is astounding and I can’t wait to see what he writes next.

‘Biography Of X’ by Catherine Lacey

When X, renowned artist, musician and writer suddenly dies, she leaves behind her widow, CM. X lived a mysterious life, one where she deliberately orchestrated personal facts about her family and past to be obscured. Neither CM, nor the public, know about her concealed past. Before she died, X expressed she never wanted a biography to be written about her. However, X’s illustrious life makes her irresistible to excavate and after she dies, writer Theodore Smith publishes a biography about her. In the throes of grief, CM is enraged by his sloppy research and inconsistencies. In wanting to correct just one mistake in Smith’s biography, CM gets lost down the rabbit hole of X’s life, uncovering the weight of her secrets and begins to realise that perhaps she never really knew X at all.

Biography Of X takes place in a parallel reality; an America split into ‘Southern’ and ‘Northern’ territories. The Southern Territory is a fascist theocracy that split from the USA after World War Two. In contrast, the Northern Territory is radically progressive, a utopia where identity politics and the importance of social services aren’t even a discussion point; they’re just a given. Lacey’s world building is sublimely dystopian, changing the course of several historical events after 1940 to result in two radically contrasting Americas.

The posthumous style of a novel within a novel is such an enticing format. The mystery surrounding X is propulsive and addictive as we try to understand why X is so formidable. From someone who is supposed to love X the most, the biography evolves from what is intended to be a factual text to something much more sinister. Adamant not to write a biography of X, CM becomes her own worst enemy as she excavates X’s life to an excruciating degree. As we begin to understand more about X in unison with her widow, it becomes addictive to watch CM orchestrate a complete breakdown of her own life. CM destroys herself in the pursuit of her wife, both in life and in death. Her grip on the biography spirals out of control as she can’t stop chasing X into oblivion. It becomes apparent that X manipulated her life in a way she is only understanding retrospectively.

‘The trouble with knowing people is how the target keeps moving’ p.36 in Biography of X

You begin to question whether it is CM, or Lacey, who is responsible when the biography starts to spiral out of control. Is it Lacey who's losing grip on her novel, or is it Lacey writing CM losing grip on the subject at hand? There is this limitless spiral of history, facade and grief that CM is getting lost in as Biography Of X interrogates; do we ever truly know anyone? CM’s inability to stop digging unravels the life she built with X and the myths that upheld their relationship. This comments on human nature's tendency to mystify those we love romantically to be more than human, and that perhaps, it is to our detriment to try and know them so intimately.

Laceys writing is hypnotising, her prose is driven by an undercurrent of unease that is propulsive. Never once does the anticipation dissipate, always managing to skilfully build on what’s happened to create an exciting disquiet about what's to come. The first Lacey I read, Pew, feels like it belongs in this universe, that it perhaps was written by someone from the Southern Territory. Both Pew and Biography Of X are interrogations on identity; who gets to reinvent themselves and explore all facets of their identity and who doesn't?

I couldn’t work out if I loved, or hated, X and I delighted in this ambiguity. I loved the mystery and ridiculousness of her life, how her past just kept growing was remarkable. All she managed to do in one, mortal life, was almost inspiring. But that in of itself is funny, because this is a faux biography. Maybe it is intended to be inspiring, about what life can look like if we allow ourselves to be honest about our desires. I’d be interested to know if anyone else felt this way after reading! Biography Of X is a buy, I recommend it feverishly and I continue to pray at the altar of Lacey - she is one of my favourite writers of all time. This book is so fun and thought-provoking, I already want to read it again.

‘The Bluest Eye’ by Toni Morrison

The idea for The Bluest Eye came from a conversation Morrison had with a childhood friend, who turned to her and said she wanted blue eyes. Twenty years later, Morrison found herself wondering where her friend learnt to believe that with blue eyes, she would be beautiful. Morrison took this encounter, and the ‘damaging internalisation of assumptions of immutable inferiority originating in an outside gaze’ to interrogate how ‘something as grotesque as the demonisation of an entire race could take root inside the most delicate member of society; a child; the most vulnerable member; a female’. 4 What she created, which was her debut (!), is a novel that explores how social and domestic aggression could cause the tragedy of a child falling apart.

Pecola and her family; Pauline, Cholly and Sam, live in post-Depression 1940s Ohio. Pecola is subjected to extensive and sinister racism and hatred, unloved by the society she lives in and her own mother. She observes how differently little white girls are treated compared to her;

‘The secret of the magic they [little white girls] weaved onto others. What made people look at them and say ‘Awww’ but not for me?’ p.20 in The Bluest Eye

And deduces that the answer is within their eyes; that if she had blue eyes, she would be beautiful and people would like her. Pecola prays each night for blue eyes like her privileged schoolmates and the girl on the Mary Jane chocolates. While Pecola's desire for blue eyes is the anchor of this story, we begin to understand where Pecola has learnt this hatred of herself from; her parents. Morrison explores internalised racism and the demonisation of Blackness in America through Pecola’s entire family. Morrison exceptionally addresses the emotional and psychological impact of being Black in America in the early twentieth century.

Pauline and Cholly are products of environments with so little love, and so much hatred, that their relationship to themselves, and wider society, is one fraught with resentment. Morrison interrogates all angles of their existence, understanding their individual intersections with race within history and culture. Morrison’s style in bringing to life those that have been culturally engineered to inherently believe they are worthless is astounding. Her prose, as ever, is intellectually expansive and emotionally charged. My favourite aspect of any Morrison novel is how she traces an emotion within a character back to its inception, which often extends beyond their lifetime into the history of those who came before. She follows it back through generations, delicately trying to find the painful moment where it all began.

Morrison creates a remarkable sense of unease throughout The Bluest Eye, by looking at the systemic racism through the eyes of children. It is eerie to read their confusion about the world, when we know the abhorrence as to why shopkeepers don’t want to take change from their hands or certain children won't play with them at school. Claudia and her sister Frieda, other narrators in this novel, question their experiences with racism with such naivety it is unsettling to read. All Claudia understands is that if she is given a white doll, she’ll destroy it, and she is horrified and confused that she wants to do this. She learns to hide her shame in love, to convert from ‘pristine sadism to fabricated hatred to fraudulent love’ and to worship American sweethearts like Shirley Temple and her big blue eyes.

Despite all that is so remarkable about this novel, in the second half Morrison starts to play with the chronology of the narrative, confusing the sequence of events. The arrestingly emotional nature of the story becomes watered down with these narrative inconsistencies, disorienting the reader about where we are in the timeline of the story. In reading the Afterword in search of an answer, I came across Morrisons own admission that she was not satisfied with how she decided to break the narrative into parts that had to be reassembled by the reader. She explains she did it because she wanted readers not to pity Pecola, but instead interrogate themselves and their role in the weight of the novel's inquiry. There is great admiration in what she was trying to do, but I agree that it didn't amount to what she intended for it to do.

Unlike Morrisons other novels I have read (Beloved, Jazz), The Bluest Eye feels as though it has a more timeless, prevalent quality to it. Pecola’s yearning for blue eyes is something which cannot be dated; the desire to change appearances to conform to a universal standard of beauty persists today. It is said most succinctly by Hilton Als;

‘Part of Morrison’s genius had to do with knowing that our cracked selves are a manifestation of a sick society, the ailing body of America, whose racial malaise keeps producing Pecolas. You can find her everywhere. She’s the dark-skinned woman trying to lighten her complexion with bleaching creams; she’s the woman who undergoes surgery to thin her lips or her nose; she’s the girl who wears colored contact lenses so that the world can see her differently.’ - Hilton Als in The New Yorker, 2020

The Bluest Eye is fictitious, but it was inspired by a conversation that was not. Morrison walking this vague line between fact and fiction asks; what does it say about American society, built on a hatred so entrenched, that a young girl whose imagination could conjure up anything in the world, wants to change the colour of her eyes so she can feel loved? I loved moments of this novel, and while I wish the narration was slightly different, I would still recommend it and call it a borrow. While the narration does go adrift, Morrison re-centres it in time for the ending which, in the least spoiler way possible, absolutely winded me.

‘On The Clock’ by Claire Baglin focuses on intergenerational exploitation in the French workplace. It follows the rhythm of fast food service and is divided into four parts; ‘The Interview’, ‘Out Front’, ‘Deep Fat’ and ‘Drive-Thru’. Baglin interperses the tedious parts of a fast food job with memories from her childhood, including the socio-economic struggles her parents faced Mostly narrated in first person, with sudden timeline jumps into the past, Baglin paints a portrait of a life of insecurity and social immobility.

On The Clock explores the hostility of the workplace; the unfriendliness of those who are in it as well as the experience of being an employee at the bottom of the ranks. The chaos of her experience in the fast food service is mirrored by memories of her childhood and her father. She recalls him constantly being let go from jobs, working unsociable hours and struggling to keep the family afloat. She recalls her mothers exhaustion in trying to feign that everything is fine, work out how to feed the family and ensure the children are having experiences, such as holidays and meals, out on an eye-wateringly tight budget. Her parents never once mention money, or their lack of it, directly to the children, but the feeling of anxiety is palpable as her parents constantly ‘murmur’ behind closed doors. She witnessed how little her parents were valued, and while she performs the oscillating monotony of her job, it seems she is destined for a life of similar struggles.

The novel comments on the soulless nature of shift work, the exploitative 0 hour contract work culture and the reality of being viewed as entirely disposable. There is a meditation throughout on the lack of agency in this nature of work but also in being working class. It recognises the impossibility in the class system and a life characterised by exploitation. I liked the concept of this novel more than the execution. I have read such profound meditations on the dehumanising nature of the workforce before (see On The Line, Of Cattle And Men) that I found On the Clock occasionally lacking. The nature of the narrative structure Baglin chooses, with confusing and never sign-posted timeline jumping, naturally created a disconnect for the reader. Just when you can feel the emotion of her childhood memories building on the page, it is violently jerked away and we are plunged back into the rhythm of her work.

Arguably, this is entirely the point, to reflect a life completely characterised by shift work, unable to ever emotionally clock out. This works well in theory, but in reality I found the fragmented narrative a little stagnant and uncompelling. Both narratives; flashbacks to her childhood and the rhythm of her working are both captivating separately, but how Baglin chose to bring them together in an almost flow state, indistinguishable prose, did not work for me.

Criticism aside, I think the nature of what this novel is trying to achieve about the lack of agency so many people have when it comes to the workforce, is done well. It’s honest in its exploration of the struggles of the working class, but also manages to be humorous despite the despair. The prose is rhythmic with the sounds and smells of a fast food joint, and it was intriguing to see how the familiar noises of fast food manifest on the page. I would recommend this book if you’re interested in literature that explores the relationship between class systems and the workforce. I’d call On The Clock a borrow. I would, however, use this review as an opportunity to recommend On The Line which was a favourite book from last year. It deals with similar themes as this, but with much more poetic deftness.

‘Cautery’ by Lucía Lijtmaer tells two parallel stories of two women more than four hundred years apart. Our first narrator is a contemporary woman living in Barcelona. From the outside, it looks like she has it all; boyfriend, apartment, impressive job and impressive friends who go to cocktail parties, but despite it all, she is unhappy. She has all the freedom in the world, but she is deeply unhappy and wonders why this is not enough?

Our second narrator is Deborah Moody, who is based on a real historical figure, set four hundred years earlier in Elizabethan England. Initially, we meet Deborah underground and from beyond the grave with the weight of the earth above her head, she recounts her life to us. How she married one of the first boys she saw and was disappointed when it turned out to be nothing like what she imagined. Eventually, she fled England for the Massachusetts Bay Colony where she found her fortune and freedom from relying on a husband. But she soon finds out that her independence from a husband doesn’t mean she is free from the dangerous vanities of man - that exists everywhere.

Cautery is a tender and humorous story about two women who share a final vision of happiness; which is breaking free from the performance of heteronormative society and starting again. I loved reading this so much that I am rendered slightly speechless about how I am going to do this story, and how it made me feel, justice. The short, snappy alternating chapters following these two women's lives, are expertly paced. They are sharp as they follow the performances of womanhood in the seventeenth and twenty-first centuries. They mirror each other in emotional intensity as we follow the ebbs and flows of their lives which should be remarkably different, but pulse with almost identical emotions. Both have their lives dictated, to varying degrees, by men and they share a similar vision of happiness which is absent of them.

Lijtmaer deftly interrogates the wounds of womanhood that have transcended centuries, presenting them as inherent to our DNA. Both engage in the performance of obedience that they know is expected of them, only to find themselves unhappy and unfulfilled. I loved the concept of two women four hundred years apart sharing similar emotional landscapes, speaking to (one of my favourite) concepts that we are not as different as we think we are to those who came before us. Deborah’s narrative was enthralling and otherworldly, while the unnamed woman of today’s narrative was tangible and relatable. Deborah’s voice from beyond the grave was comforting and humorous, I loved being with her on the page. While the two narratives are set in such drastically different time periods and landscapes, there is an impressive commonality between them.

Much of my love for this novel comes down to how it made me feel; how human it felt in its exploration of the desires of women across the centuries. I kept picking up this book at every spare moment, entranced by the women, absorbed in wanting to know what they’d do next and where life will take them. It felt familiar in a sense that feels uncomplimentary to say, but I mean it in the highest regard. Cautery felt like a story I had read before, familiar in its exploration of enraged women, but innovative in the way Lijtmaer chose to explore these themes across centuries. She challenges the sacrifices women make for the supposed greater good, and positions them as being to our detriment. Despite the faux feminist impression this review might be giving, that is not the tone of this novel - it is just the story of two women worlds apart in reality, but arm in arm in their fury.

It was a pleasure to read this novel. I loved how sarcastic and cutting Lijtmaer was in her prose and was enthralled by the story. I loved every word and moment with these women and felt so buoyant when I finished it. This is my favourite read of the month without a doubt. I love historical fiction, so Deborah’s narrative was my favourite, but it complimented the twenty-first-century narrative in the best way. I enormously recommend this and call it a buy! This is the best Charco Press I have read this year - which is high praise because The National Telepathy was a tough competition!

‘On The Calculation of Volume I’ by Solvej Balle

Tara Selter is stuck on the eighteenth of November because she has slipped out of time. Every morning she wakes up to the same day. She comes to know the shape of the day like the back of her hand. She knows when it will stop raining, when her husband will go for a walk and when the neighbour will walk past her window. It hasn’t always been this way, Tara used to move with time like the rest of her, but something happened to her and now she is stuck. For everyone else around her, this day is lived for the first and only time. For them, there are no other eighteenths of November and tomorrow will be the nineteenth. They do not believe Tara when she tries to tell them she has been stuck, on this day, for almost a year. On The Calculation of Volume I follows Tara as she tries to make sense of time and desperately recognise a pattern to help her escape. As she approaches her 365th eighteenth of November, she is determined that she can manufacture an escape from this time loop.

This novel simmers with anticipation and dread as we follow Tara perpetually stuck in time. It is remarkable that Balle can write about the same day, patterns and habits and it does not become monotonous. Instead, Balle writes with poetic beauty about the shape of the day and the sights, smells and sounds that have come to characterise Tara’s existence. The concept of this novel is fascinatingly bizarre and connects to a deeply human fear about being stuck in the same day for eternity.

Initially, Tara wakes up everyday and proceeds to tell her husband, Tom, about what has happened. She involves him in her time warp, desperate for company and solidarity in her mind bending reality. He always believes her, but as the days go on, she becomes more weary. Involving Tom becomes exhausting and the more she loses grip on reality, the more she dives into a deeper solace. This quiet meditation of marriage is profound and devastating. Their intimacies fade as time comes between them, commenting on the limits of sharing a life, and time, with someone. Balle suggests that love, perhaps, is not as timeless as we would like to believe and is instead inherently rooted in the construct of time.

Tara remains determined despite her recurring nightmare. She does not unravel, and instead uses the stars and the seasons to create her own catalogue of time. Tara is having to rethink time outside of how humans have come to categorise it; if there is no past or future, how is it measured? The plot of this novel is so unnerving it becomes addictive to keep following Tara, to see what she will do next and how she will continue to find new ways to notice things. There is no technology in this novel, once she is stuck in the eighteenth of November her phone dies and collects dust in her room. Without this, it is as if Tara is forcibly reconnected with a humanity that we have all lost, one that is more intimately connected to the world around us. There is an element of romanticism here in her turning to the seasons and the stars to figure it out, rather than spend hours a day trawling the internet to find answers. You cannot help but continuously put yourself into Tara’s shoes; How would I make sense of time if I had nothing to measure it by?

Balle interrogates the unique, untranslatable ways we all inhibit time and the traces we leave in this world. Time has changed irrevocably for us in our society, our world now feeds off the trajectory of the future perhaps more than ever, and this novel is almost the antithesis of that. In her perpetual groundhog day, Tara meditates on life in a way that feels unbelievable in its considered nature.

This novel is a remarkable reflection on a period of time in my life so unique that I rarely ever find literature that aligns with it, which is my experience of being bed-bound for two years. That was my own experience with living the same day on repeat for an eternity and while I did not start reading the stars, I was stuck in my own time loop which no one else understood. There is no past or future when you’re bed-bound, you lose all anchors of your identity, you simply fall out of the world. Every aspect of humanity which means so much to everyone else; clocks, calendars, time moving forward, becomes meaningless to you. On The Calculation of Volume I meditates on this sense of being profoundly lonely in a world that is turning without you; stranded in a continuous cycle of observations. You become completely detached from conventional markers of time that is a herculean experience to describe, yet Balle achieves in trying to communicate the indescribable insanity of it and how it causes you to turn inward.

I loved this, would absolutely recommend it and call it a buy. I think this is a story for a particular reading palate; one that enjoys speculative fiction with extensive observation, contemplation and philosophical commentary about humanity and the concept of time. On The Calculation of Volume I is the first in a seven part series, so I am fascinated to see where this will go - will Balle actually meditate on the concept of time and our relationship with it for seven novels? Are we really going to read hundreds and hundreds of pages about the eighteenth of November? I am ready to find out. I have already started Vol II, so stay tuned for that review in April!

And that concludes my March Reads! My favourite books of the month were ‘Biography of X’ and ‘Cautery’.

My first read of April is ‘On The Calculation of Vol II’ by Solvej Balle because I can’t resit! I am almost finished with it and I am enjoying the direction Balle has taken - not what I expected (I’m not sure what I expected?) but I am impressed.

End Notes

My interview with Saou Ichikawa, author of ‘Hunchback’ which I read at the end of last year, came out last week in

’s newsletter, Books + Bits! It was my first author interview, which was nerve wracking and a lot of fun. A big thank you to Pandora for the opportunity, guidance and editing. <3The Women’s Prize for Fiction Longlist list came out at the beginning of March, which now feels like a lifetime ago! The titles that caught my eye are:

‘Amma’ by Saraid de Silva

‘Dream Hotel’ by Laila Lalami

‘The Persians’ by Sanam Mahloudji

‘Fundamentally’ by Nussaibah Younis

Let me know your thoughts:

❀ What have you read and enjoyed in March?

❃ Have you read any of these books? Would you like to?

❁ Do you have any book recommendations for me based on the themes of this month?

Thank you, always, for reading.

See you next month,

Happy Reading! Love Martha

If you know someone who is wanting to expand their reading life in 2025, share this newsletter with them!

Catch up on what you might have missed:

And what I was reading this time last year: (this was a good month)

Remember to subscribe if you enjoyed this and want to receive recommendations straight to your inbox!

I endeavour to always introduce you to books that don’t get coverage elsewhere - that is a promise.

Derogatory.

I couldn’t really find any criticism of The Savage Detectives which is interesting… why is it buried so deep on the internet? If anyone knows of any good criticism can you please let me know. All I could find was this which made me laugh ‘A few years ago, I attended an academic conference where a prominent scholar of Latin American literature announced that he hated The Savage Detectives, a novel he considered overwritten and overrated. The statement provoked enthusiastic hooting from the back of the room, as if in glee at a taboo being broken’ - wish I was in that room, I’d hoot too.)

Quote from p.20 in On The Greenwich Line

Quotes from p.xi in the Foreward in Bluest Eye

I fly to my laptop and make a quick tea or coffee and find somewhere comfortable to sit the instant I see a Martha's Monthly notif pop up on my phone or in my email inbox- Love hearing your takes on the much-discussed Balle & modern classic Biography of X (both of which I hope to get to sooner or later...) as well as Cautery and On the Greenwhich line, which both have been hovering in my periphery. Back in the Day is a new title to me, but your description reminded me of a book I've recently read and have been thinking about a ton called The Passenger Seat, which is also about teen boys, aimless, who kind of spiral toward violence (and it's told from a distinct distance). Thanks as always for the many recs Martha!

I am running so behind on my Substack reading this week because of work-crazy but I loved this collection, Martha! I am thrilled and relieved that you loved Biography of X - I share in worshiping at the alter of CL. This book in particular is the one book that I have read in the past year that seriously made me whisper - can we do this!? Just the way she bends fact and fiction so seamlessly was absolutely fascinating and as someone who is working on a novel inspired by but not faithful to historical events and figures, this book felt like a liberation to me. It made me realize that as a writer, your one responsibility is to tell an interesting story and make your reader FEEL something they have never felt before. Your ambiguity re: X is just such a perfect example of that. Do we love X? Do we hate X's guts... why decide?!

Cautery sounds AMAZING and I will definitely look for it. What a strange choice of characters to pitch against each other. I am so intrigued!