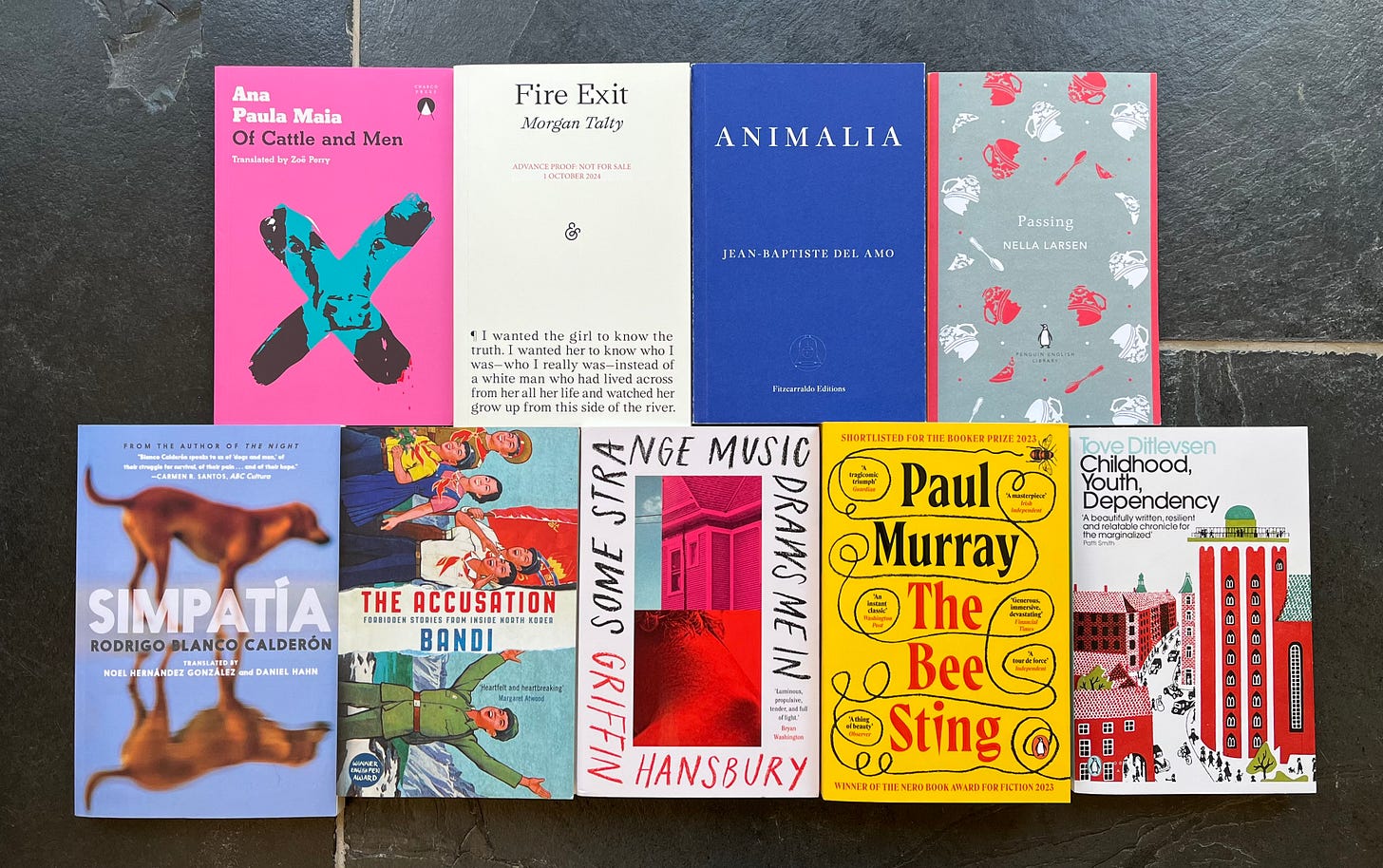

Welcome to ‘Martha’s Monthly’, September Reads edition! September was a reading month where the themes were glaringly obvious. Almost all the books this month explored the emotion of shame; intimately and societally. In a variety of ways, the books address the devastating impact of feeling shame and how this affects people's lives.

Another theme explored by two books this month was humanity’s hostile relationship with nature. These novels ambitiously interrogate the interdependence of man and animal, but more specifically, our relationship to farming and food production.

To see the translated reads from September on Martha’s Map, including authors from Venezuela, Denmark, Brazil, France and North Korea, click here.

For those who are new, buy, borrow, bust is my recommendation key: Buy = I immensely enjoyed and highly recommend this book. Borrow = I think this book is still well worth a read and I’m glad I read it. Bust = I wouldn’t recommend this book from my own reading experience.

‘The Bee Sting’ by Paul Murray is set in rural Ireland in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crash. The Barnes family, until recently, ran the biggest business in town. Now they are facing financial-ruin and the whole town is watching. The Barnes' are plagued by a past they cannot live up to. Dickie and Imelda’s marriage is hanging by a thread and they are too consumed in their own problems to realise that their children, Cass and PJ, are struggling. Straight-A student Cass seemingly doesn’t care about school anymore and PJ is being relentlessly bullied. Aside from PJ, they are all trapped within their own self absorption, unable to notice that they are rapidly moving toward a precipice. The novel is an intimate and propulsive character study of a complex family who are haunted by the ghosts of their past. Murray questions how far can you go back into the roots of a family to find out where it all began?

This novel is all about shame, dishonesty and the value of truly knowing yourself. ‘The Bee Sting’ explores how shame can eat you alive, affecting the way you behave until you’re suddenly living a life where you feel trapped. While the concept of this novel seems straight-forward enough, Murray uses an abrupt and genius structure in order to tell the story. Murray reveals the family in a carefully considered climax; four large point-of-view chapters, one dedicated to each family member. Our initial introduction to the Barnes family is through Cass and PJ. While they are slightly less compelling, they offer a very interesting initial window into the real stars of the novel; Dickie and Imelda. Cass and PJ are both gripped by characteristics and desires they can’t seem to place. Not helped by their parents' complete lack of awareness, they are our first insight into how this family operates; the relationship they have to the truth and the emotional atmosphere within their home.

Imelda is a prickly character, evidently deeply unhappy with her life and the choices she has made. Her resentment runs deep, she can be hostile and irritable. Dickie is equally as unhappy with the choices he has made, but contrary to Imelda’s anger, he is withdrawn and disconnected. Both feel shame towards their past, and their present, feeling humiliated and full of regret, but unable to express or understand this emotion. Murray paints a vivid and empathetic picture as he reveals the hopes, desires and dreams of Imelda and Dickie before they became parents. To learn about their childhood, adolescence, and how this has shaped Cass and PJ, was addictive. Murray introduces the Barnes family to us as an unlikeable package, but skilfully uses the narrative to create remarkable emotional depth within each of them, helping us to intimately understand why they behave the way they do. I think Murray does this exceptionally. By the end of the novel, I did like all of them and felt I deeply understood them, which is significant, because at the beginning I thought each of the Barnes’ deserved whatever they had coming for them (except for PJ).

Throughout, Murray explores grief exceptionally. He interrogates how grief is multifaceted and frequently not confronted. While this includes the grief felt in the face of death, Murray also explores it in relation to grief of a life you thought you would live, the grief of a dream that has not come to fruition. The Barnes family demonstrate how grief can become a shame people carry around, often building a life in its shadow. Within the emotions of grief and shame, Murray interrogates the cruel realities of life, not shying away from how grim and bleak it can get. The novel meditates on how much of a hand we have in controlling our life? Are we at the mercy of a fate we cannot see, planted within the family generations ago? It ruminates on is there blame for the impending disaster the Barnes’ are facing; is it an individual, such as Dickie and Imelda, or is it someone, or something, else?

‘The Bee Sting’ was consuming, gripping and well paced. Although the prose was good, it was not in any means exceptional. It was the plot, pacing and characterisation of the novel that made the story shine. Murray faultlessly envelopes us into a true-to-life world without ever being boring or predictable. Each Barnes had a distinct voice, compelling and vulnerable in its own way. Murray’s ability to discern between each unique voice, while maintaining the concept of a family with a shared interweaving history, was impressive.

I loved this book. At its core, it is such a good story. ‘The Bee Sting’ is a classic family saga, a story rich in twists and entertainment. I was engrossed by the family and their inability to understand their emotions and talk to each other. Their neurotic approach to lying to themselves, and each other, in order to deal with their reality was brilliant. It was like watching a car crash waiting to happen, and I would probably not be the first to suggest that 642 pages did not feel long enough. It was a pleasure to read and utterly compulsive. I would absolutely recommend this novel and call it a buy. I have seen a few comparisons between ‘The Bee Sting’ and ‘The Corrections’ by Jonathon Franzen, so that will be a novel I will be making a point of reading sometime soon. (Is that an appropriate comparison? If you’ve read both, let me know if you think that holds up.)

‘Simpatía’ by Rodrigo Blanco Calderón. Ulises Kan’s wife, Paulina, texts him telling him she is leaving him, and Caracas. Paulina does not have a good relationship with her dad, but after she moves away, Ulises befriends her father, General Martín Ayala. They quickly form a bond, and both appreciate a love for dogs. When Ulises' father-in-law dies, he discovers that he has been bequeathed the task of turning the family mansion into a shelter for abandoned dogs. But there’s a catch - it has to be done within the designated forty-day time period. If he manages to do it in time, he will inherit the luxurious apartment that he shared with Paulina. If he does not, Paulina will get the apartment and Ulises will lose his only opportunity for security in the collapsing city of Caracas.

‘Simpatía’ is set in Venezuela amid the collapse of Chavismo and the mass exodus of the intellectual class who have been leaving behind their pets. The novel explores Venezuela’s post-Chavez economic and social crisis, which severely affected day to day life in the country. It resulted in an enormous food shortage, but most significantly, a refugee crisis and a sharp rise in crime. ‘Simpatía’ paints a picture of Venezuelan society at the time; the corruption and manipulation that was taking place within the institutions that held power. It is a story about those who are left behind in a cleared-out city; humans and animals, and what they need to do to survive. The plot gives us glimpses into the challenging realities of life in an abandoned city and the struggle many people had in meeting basic needs.

The story is a political allegory, and the dogs represent the treatment of the people in Venezuela. This metaphor is clever from Calderón. ‘Simpatía’ tells a complex and fun story about what societies choose to care about, protect and hurt in a time of crisis. It presents a carelessness and cruelty that has emerged under Chavez, how willingly their basic rights are being abandoned by their leader, instead just being used as pawns in a political game. There is an ominous feeling throughout ‘Simpatía’, which is strengthened by Calderón’s lack of explanation of any character. The reader is dropped into a confusing world, and we have to try and figure out ourselves who Ulises can trust. There is a prevalent atmosphere of suspicion and unease, created by Calderón to reflect what it was like at the time. The novel reads like a thriller as we are suspicious of some questionable behaviour taking place, we don’t know who to trust or believe (until the end).

I was impressed by this whole novel. I think using the dynamic between dogs and humans to reflect the relationship between the government and the people was innovative. Reading ‘Simpatía’ was an enjoyable experience and I felt attached to the story, the characters and finding out what was going to happen. Ulises’ character seeks to explore the relationship between love, power and morality in a very interesting way. I am anticipating some readers thinking this novel sounds strange and ridiculous, and I would agree that on the surface, it does. But, underneath it carries much more profound messaging, and that is what makes it so fun! Calderón asks you to read between the lines; to understand the suffering dogs, and then translate that understanding to lived experience in Venezuela under Chavez’s presidency from 1999-2013.

‘Simpatía’ paints a rich picture of what life was like, tangibly conveying the struggles and providing a unique avenue into understanding Venezuelan history and politics. Despite an ambiguous ending that I did not know how to interpret, I loved reading this. It was easy to read and engaging. I thought the way Calderón wrote was fantastic. I am intrigued by his other novel, ‘The Night’. I would recommend this to anyone who likes to read slightly alternative historical and political fiction. ‘Simpatía’ is a buy!

‘Fire Exit’ by Morgan Talty. Charles, a white man, lives alone beside the river on the edge of the Penobscot reservation in Maine. He spends his days looking after his depressive mother, who has dementia, and staring across the river to the house where his half-Native daughter, Elizabeth, has grown up. Elizabeth does not know who he is, because her mother decided to keep Elizabeth’s paternity a secret to protect her tribal status. After watching her all his life, Charles can see Elizabeth is struggling, just like her grandmother. Charles is convinced that Elizabeth finally needs to learn the truth about who she is. However, Elizabeth’s mother fiercely opposes the revelation of this truth, because it will threaten Elizabeth’s position within the tribe.

Before I get into my reflections on the novel, I want to start by discussing my expectations versus the reality of the novel and how this impacted my reading experience. I think this novel is inaccurately described. The blurb suggests it is a story of a profound search for identity, interrogating why it is so important for Elizabeth’s paternity to be kept hidden. It was unclear to me why Elizabeth’s paternity was so shameful and the importance of concealing it. It wasn’t until I read the press release from the publisher that I understood what Talty was attempting to explore within the novel. Talty recounts how, in the Penobscot tribe, you need at least 25% Penobscot blood running through your veins to have membership in the tribe. Talty addresses this (again, in the press release not the book);

‘Blood quantum is a colonial tool that many federally recognised tribes use to keep track of citizenship. [...] This was before we knew these men, the so-called white Fathers, had plans masked as survival but were intended for us to eat each other’s spirit piece by piece. This is before colonial construct is in our vocabulary’ - Morgan Talty in the And Other Stories press release

This quote discusses the categorisation that exists within Native American tribes; a government tool rooted in attempting to encourage internalised violence. Therefore, I anticipated the novel to explore the challenges Native Americans experience in the face of not being indigenous ‘enough’. Instead, this novel is about the story of Charles and his relationship with his deteriorating mother, neither of whom are Native American. Instead, they live among the Native American community. The role of Elizabeth within the story felt like a subplot, rather than a central one. She exists on the periphery, as someone not yet included in the story, because she has been denied that opportunity. I didn’t think this plot line was bad, but I do think the novel is incorrectly described.

I anticipated something more profound in the discussion around Native American identity. The novel very subtly touches on how it is shameful Elizabeth has a white father, but I wish this was interrogated more deeply. How does this intersect with the violence and prejudice that exists within the community? What would Elizabeth’s life look like if she knew this? I would have loved an exploration of someone who did have Penobscot blood, but not ‘enough’ to be a member of the tribe. This felt like a missed opportunity. However, I don’t want to put too much emphasis on what Talty didn’t do, and give some attention to what he did. There is a palpable atmosphere of tension running throughout the novel, as you are waiting for the big reveal; for Elizabeth to find out. The novel explores the idea of family, chosen family and alliances. Talty explores the role of long-standing secrets in order to protect the ones you love. ‘Fire Exit’ was very easy to read, with incredibly simple and straightforward prose. The prose does not encourage rumination off the page, creating a story that is clear and direct. Gripped by the possibility of Elizabeth’s secret being exposed at any moment, ‘Fire Exit’ is an arresting read. The thrill of a secret is always a good thrust for a novel, it undeniably creates propulsion, no matter how the story unfolds.

‘Fire Exit’ is all about the role of stories; stressing how Elizabeth does not know hers, preventing her from truly knowing who she is. The novel challenges the significance of secrets in relation to someone's identity. I raced through the book, it was consuming as we waited to find out how Charles would tell Elizabeth about her paternity. Although I felt disappointed in the trajectory of the novel, I still enjoyed my experience of reading it. I would recommend this if you are seeking a read about the challenge of caring for a deteriorating parent. I would call ‘Fire Exit’ a borrow.

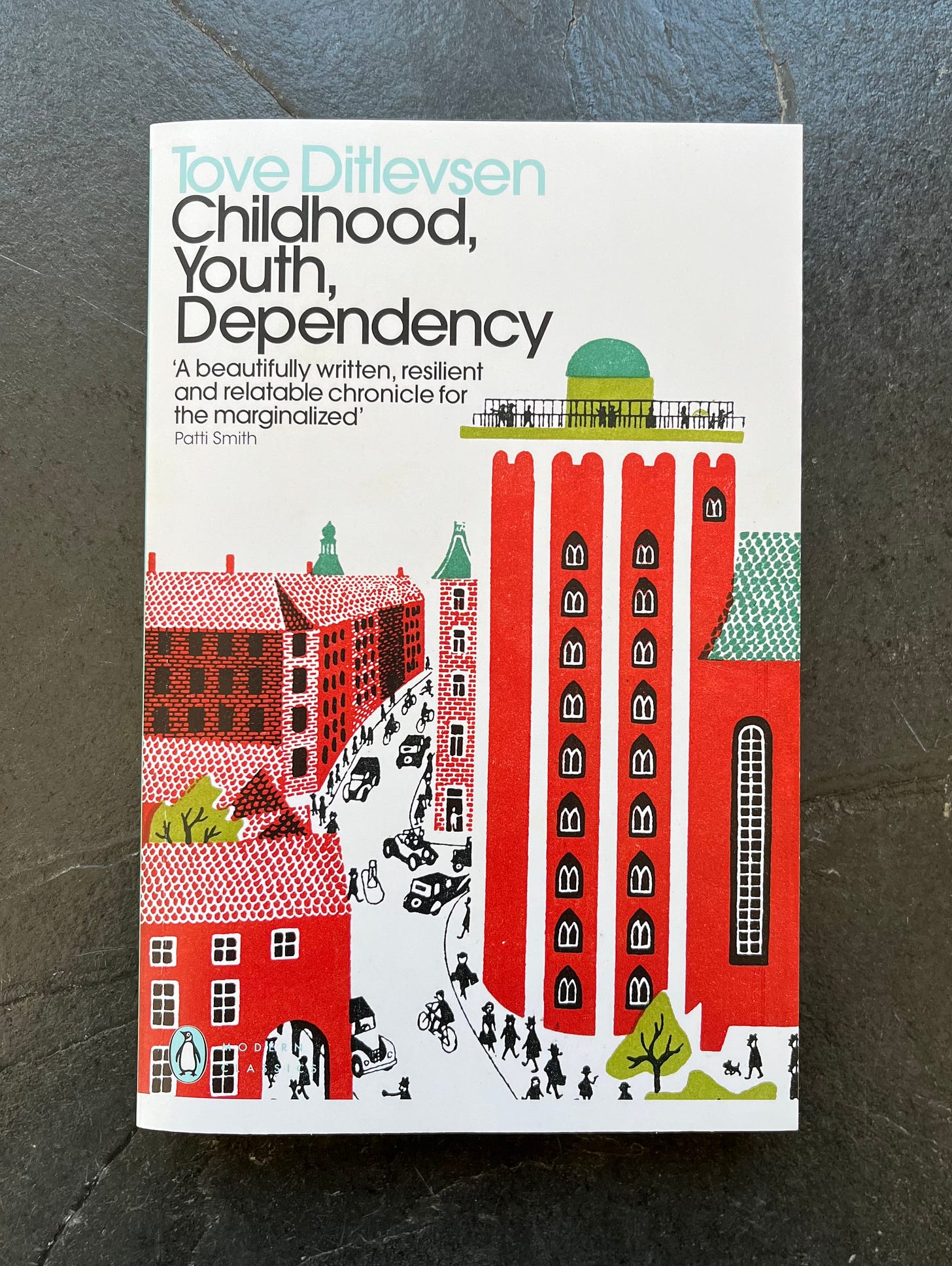

‘Childhood, Youth, Dependency’ by Tove Ditlevsen earnestly explores life in Denmark as a woman in the early twentieth-century. Ditlevsen recalls her life from girlhood in working-class Copenhagen, to her struggle to pursue her dream of being a writer and her experience of motherhood. ‘Childhood’ recalls the experience of girlhood within poverty, feelings of exclusion and not being able to conform. It is throughout ‘Childhood’ we get to know Ditlevsen; her character, family, hopes and dreams. Ditlevsen is captivating to read as she frankly expresses the myriad of ways she feels like she does not belong within her family or society;

‘I smile in agreement as if I’m also looking forward to such a future, and as usual, I’m afraid of being found out. I feel like I’m a foreigner in this world and I can’t talk to anyone about the overwhelming problems that fill me at the thought of the future’ p.84 in ‘Childhood, Youth, Dependency’

‘Youth’ describes Ditlevsen’s early experiences of work, sex and independence, while ‘Dependency’ explores the devastating lure of addiction. Ditlevsen writes about the female body in a searingly honest way. She interrogates how sex, marriage and motherhood were heavily politicised in the early twentieth-century. Ditlevsen comments on how these aspects of women's lives were a currency and security. The trilogy is full of candid discussion about the economic prospects of marriage and the importance that is being imparted on Ditlevsen as a child, by her mother, in order to secure a future. Ditlevsen had ambition to be a writer, something that was ridiculed and perceived as an impossible endeavour for her. While she did become an author, there is nuance in her writing that acknowledges the role she was expected to play with becoming a wife and mother. She was dismissed by the critical establishment during her lifetime for being a working-class, female writer. Right from childhood, it is evident Ditlevsen found the societal expectations placed on her to better her economic standing suffocating.

Ditlevsen’s memoir is characterised by struggle, ambition and addiction. I do not wish to reveal anymore about her life, because I think it spoils the book. The searing honesty throughout the trilogy, something which is valued today, would have been unbelievably scandalous at the time. Ditlevsen is a pioneer in her decision to recount her life on the page, devastatingly addressing some of the most difficult parts of life as a woman in the early twentieth-century. She recounts a life lived on the periphery due to her gender, family and addiction. Ditlevsen writes with exceptional honesty, despite having aspects of her life that she would have been extensively shamed for. She admirably addresses such complex matters in very few words and I was enamoured with her lyrical prose. Despite being published almost sixty-years ago, Ditlevsen’s writing about womanhood and female identity is continually pertinent.

This book was unbelievably good, and because of that, I am struggling to articulate just how much I loved it. Tove Ditlevsen was an innovator and I am in awe of her writing. ‘Childhood, Youth and Dependency’ is a beautifully written novel about the tension and variety of human experiences that can be contained within a singular life. I found her endearing to listen to, her work is intense and immersive. This is going to be one of my favourite books of the year - I can feel it. I enormously recommend this and call it a buy. I recommend ‘Childhood, Youth, Dependency’ for those who enjoy honest, unflinching stories about the complexities of womanhood and the struggle to find, and maintain, an identity. I now want to read ‘The Faces’ by Ditlevsen. May this review be a written account of me becoming a Tove Ditlevsen superfan. Since finishing the trilogy, I have been consumed by googling her; hungry for any more information I can find about this remarkable woman.

‘Of Cattle and Men’ by Ana Paula Maria. Protagonist Edgar Wilson is a chief stun operator. He makes a sign of a cross on the forehead of a cow, and then stuns it with a mallet. He does this over and over again at Mr Milo’s slaughterhouse, consistently reliable and following orders. He takes pride in the way he approaches killing the cows, trying to be as humane as possible and stressing the importance of keeping them calm. However, something is afoot and the cows seem unsettled. They start behaving unpredictably; one runs headlong into the side of a barn, while twenty-two others throw themselves off the side of a cliff. There is something driving both the men and animals to murder and madness. Is it a predator, or is it something bigger?

‘Of Cattle and Men’ is a punchy fable about the complex relationships between humans and animals. There is an immediate unease right from the beginning of the novel, an energy that is substantial but hard to identify. Edgar is our eyes to witnessing the day-to-day life at the abattoir as we are thrust into a world completely characterised by relentless murder. There is a particular contemplation within the prose about the value of life. As the story continues, the cattle and the men begin to mirror each other as the novel becomes more claustrophobic. ‘Of Cattle and Men’ asks how humanity distinguishes between murder, death and food. Through the cattle, Maria is interrogating the differing relationships we have to death and murder.

‘As long as there’s a cow in this world, there will be a man keen to kill it. And another keen to eat it’ - p.97 in ‘Of Cattle and Men’

I read a abattoir book earlier this year (On The Line) and felt prepared in what to expect when it came to the vivid and relentless descriptions of a slaughterhouse. However, this did not make Maria’s prose any less confronting. What both novels ruminate on exceptionally well is how we consume, as well as the rate in which we consume. Both operate as a confrontation on the dehumanisation of the animals and of those doing the killing. They critique the role that capitalism has had on the sheer scale of meat production and how it has desensitised our relationship to the natural world and other living beings.

‘Of Cattle and Men’ is about the system that has been built around meat as food. It addresses how this industry is inherently hierarchical; those who kill, process and consume. Maria ruminates on whose life is more disposable - the cattle or those who kill them? Job security for those who work in these environments are notoriously precarious and underpaid. Maria is questioning the worthlessness attached to those working in the industry and what that says about humanity's relationship to violence.

The novel undoubtedly has a religious undertone, one that questions how one life is different from another in importance? Who are we (humanity) to decide who gets to live and who gets to die? There is a subtle aspect of the novel that is implying we are playing God; playing too fast and loose with life and how we value it.

‘In any case civilisation has made mankind if not more blood-thirsty, at least more vilely, more loathsomely blood-thirsty… Now we do think bloodshed is abominable and yet we engage in this abomination, with more energy than ever’ - Fyodor Dostoyevsky in ‘Notes from Underground’ on p.99 in ‘Of cattle and Men’

Eerie and unsettling, ‘Of Cattle and Men’ is deeply thought provoking about humanity's relationship to violence. While I have been writing this review, I have not been able to stop thinking about all the philosophical questions and discussions this novel triggers. I think I could go on writing indefinitely about all the questions this novel asks. I always appreciate novels that serve as a poignant reflection on society. This is a novel that is anti-meat, but not aggressively so. It critiques our relationship to consumption, how unsustainable it is in scale, the damage it causes and the impact of capitalism on our relationship with the sanctity of life. I would recommend this book and call it a borrow. The novella is such an imaginative approach to a discussion about the production of meat, which is already well established. Maria has turned the conversation on its head by bringing in the cattle as characters learning to exercise their own free will.

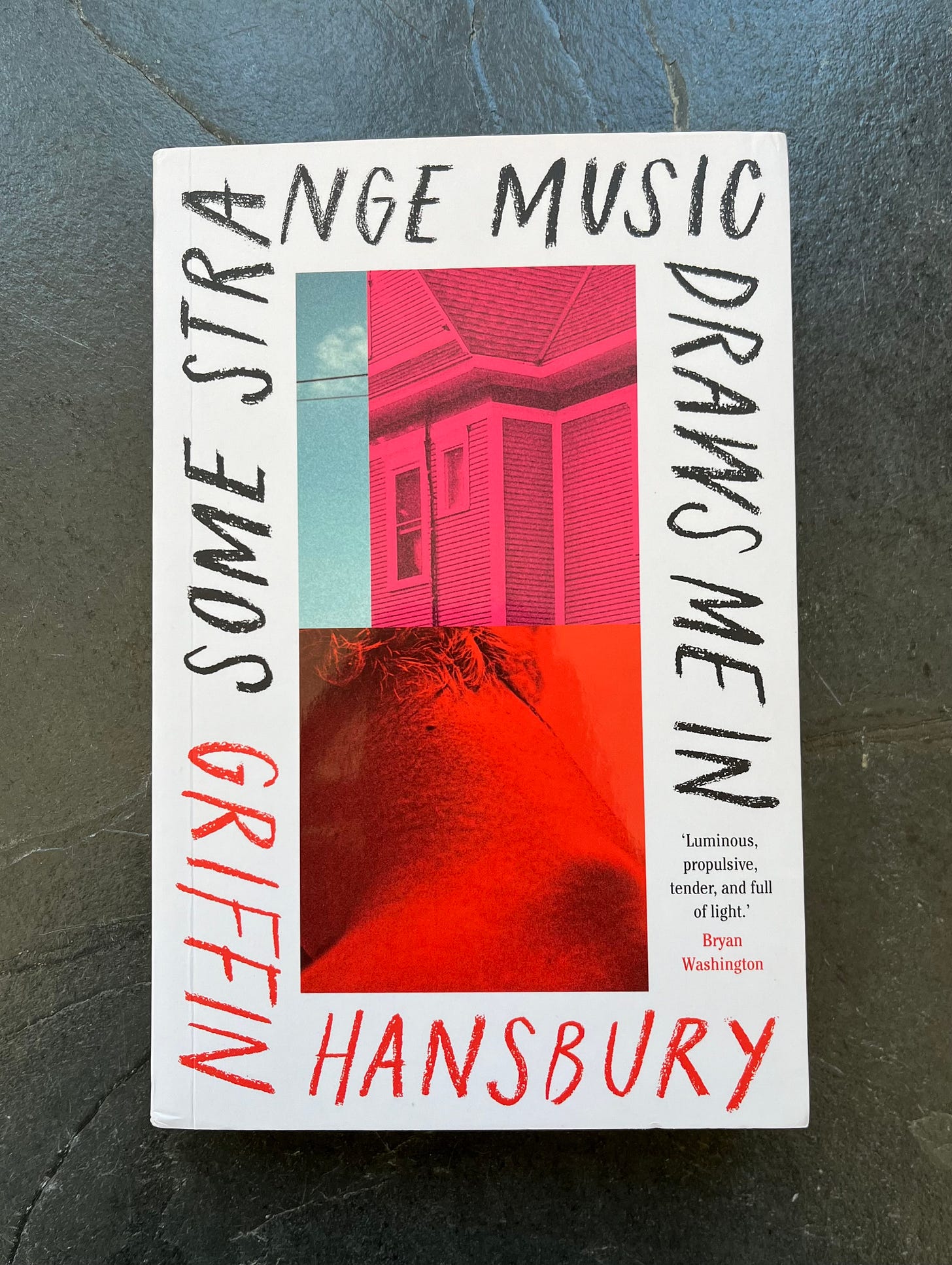

(A caveat for this review: This novel is about transitioning. In Mel’s 1980s narrative, Hansbury uses the pronoun ‘she’. In Max’s 2019 narrative, he uses the pronoun ‘he’. This use of both names and pronouns are present in the blurb. Because of this, I will be using ‘she’ and ‘Mel’ when referring to the past narrative and ‘he’ and ‘Max’ when referring to the present narrative. I considered this for a while and I deeply appreciate that every trans person is different on how they would like to be referred to pre transition. I am choosing to reflect Hanbury’s choice of pronouns in the story he has written. I would never refer to someone using their dead name and pronouns, unless specified. <3)

‘Some Strange Music Draws Me In’ by Griffin Hansbury. In the summer of 1984, in Swaffham, Massachusetts, 13-year-old Mel encounters someone who changes her life forever. While drinking a slushie in a drugstore, Mel first sees Sylvia, a trans-woman. Sylvia’s confidence and swagger captivates Mel and stirs an emerging trans self-awareness within. For the first time in thirteen years, Mel has seen someone different, someone who challenges gender and sexuality in a way Swaffham has never seen before. However, Sylvia’s unapologetic presence sparks fury in working-class Swaffham and the town begins to develop a hostility towards Sylvia, putting Mel into conflict with her mother and best-friend. Sylvia is a catalyst for Mel, as she realises there is a life beyond her small town and other ways of being. Narrating this coming-of-age tale in 2019 is Max, formerly Mel, who is on probation from his teaching job for defying speech codes around trans identity. Returning to Swaffham, he is forced to confront his fractured family and reflect how his relationship with Sylvia changed his life forever.

Hansbury has written a poignant coming-of-age story about the power of being different. From the beginning, we know that Mel transitions, and becomes Max. The gap between Mel and Max’s alternating narratives is a window of thirty-five-years, and we are left wondering how this journey of self-discovery took place. Mel is introduced to us as someone who does not feel like she fits in, but does not have the language to label her feelings. We ache for the struggle she is experiencing; trying to understand who she is in an environment that is determined to suffocate her. Mel’s narrative explores how frustrating and shameful it was to try and understand gender, as a child, at a time when those conversations were not taking place. I thought Hansbury captured the angst and emotion of early adolescence exceptionally. Often experiencing things for the first time, Hansbury gives every emotion Mel is grappling with the space and intensity it deserves. The novel perfectly articulates the all consuming feeling of jealousy, confusion of desire and the frustration towards the unknown.

Mel’s narrative also explores stereotypical working-class towns and the impact that this environment has on those who grow up in them. While we know that this environment is trapping Mel, but there is room in the narrative to recognise how it traps others too. Retrospectively, Max recognises that everyone else was similarly trapped, but he couldn’t see at the time. Hansbury articulates how these places are incredibly threatened by people who are different. Mel gets an opportunity to view life differently because of Sylvia, something which her peers and family do not.

Max’s narrative addresses the inter-generational difference that exists within the queer community, exploring how much has changed since the 1980s for trans people. Max being put on leave for not conforming to speech codes around trans identity is ironic and problematic. Max is struggling with how much the language and terminology used to talk about trans people has changed. He can’t understand why certain words are banned and the emerging use of they/them pronouns. Hansbury honestly explores the politicisation of gender today and how elders of the trans community might struggle with how differently transitioning is handled by today. While this exploration reaches no finite conclusion, I thought the discussion around how older trans people might feel excluded from the queer landscape today was interesting. Max’s narrative sincerely expresses how challenging it is to exist within a body that is never quite ‘right’ in the eyes of our society;

‘Nobody wants to hear about my anger. There’s too much of it. I got the double whammy. First the rage of living as a girl, told to be good, be quiet, be still, followed by the rage of being a transsexual man, unseen and un-understood, alone, erased, and more recently, told, again, to be good and quiet. In one body or the other, girl or man, I am getting it wrong.’ p.21 in ‘Some Strange Music Draws Me In’

This novel is full of discussion about what it means to be trans, both from the perspective of a young person trying to figure it out and an adult who has grown so much. Both narratives explore a range of aspects around transitioning, emphasising the tremendous challenges that all stages of a trans person's life hold. ‘Some Strange Music’ addresses the significance of giving children the opportunity to have a range of representation around them to show them that change is possible. The novel operates by demonstrating how different Mel’s life would have been if she had not met Sylvia, but simultaneously, how important it will always be for queer people to have older role models to look up to.

Hansbury has captured the complexities of the struggle of understanding yourself and the landscape of intergenerational queerness. The novel is full of nuance about gender identity and the challenges of coming from a place where you are not given the opportunity to express yourself. Incredibly easy to read and full of emotional depth, I enjoyed this book and would call it a buy! I appreciated reading the perspective of a young adolescent's curiosity about gender and transitioning. It was really beautiful to witness Mel begin to understand the possibility that exists. This is not a perspective I have come across before, and it gave me a much better understanding of the physical and emotional turmoil of questioning your gender at a young age.

‘Passing’ by Nella Larsen tells the story of Clare Kendry and Irene Redfield, two African-American women in 1920s America. Irene, our protagonist, has a desirable and respectable life. She is married to a Black physician, lives in a comfortable house in Harlem and arranges charity balls that gather Harlem’s elite. Clare, on the other hand, has severed all ties to her past. She is fair-skinned, ambitious and married to a racist white man who is entirely unaware of her heritage. Clare is leading a life of deceit in order to better her social standing. When both women encounter each other for the first time in over a decade, both of their lives begin to unravel. Irene is thrown into panic at the consequences and risk in Clare’s behaviour. Whereas Clare views Irene’s life with a tinge of envy, as she learns of the vibrant community she has left behind, she has a burning desire to come back. Clare and Irene’s reignited relationship threatens to shatter both of their worlds, but whose world will break first?

I decided to read ‘Passing’ this month with

and her Closely Reading Book Club! ‘Passing’ has been on my radar for sometime, and it felt like the perfect encouragement to finally read it. If you have read ‘Passing’, and would like to read some exceptional analysis from Haley, as well as my thoughts on the ending, you can click here. However, in this review I will, as usual, keep it spoiler free.‘Passing’ is an emotionally charged and captivating story about the enduring impact of racism in American society in the 1920s. These women live in a world of Jim Crow laws and segregated public spaces. I was immediately enamoured by the plot, which injects a consistent sense of unease throughout the novel. Larsen has written a novella with a propulsive concept, one which grips you until the very end. Larsen is directly challenging everything that upheld American society at this time, disputing the racially segregated foundations of America as precarious and absurd. This is upheld by Clare, a woman who is Black but has managed to deceive her way into ‘white society’. There is a current of danger throughout the novel as we, the reader, are waiting for the moment when Clare’s secret is revealed. I could not make up my mind how I felt towards Clare and her decision to pass in order to secure a different life for herself. Yet, I enjoyed this constant indecision.

Larsen has created a thought-provoking novel about 1920s American society in a subtle way. She explores the politicisation of everyday life, examining the impact of segregated public spaces within the home and relationships. Generally, we witness Irene and Clare interacting within private spaces, and yet the societal attitudes toward segregation permeate these spheres. Despite Clare and Irene sharing the same racial background, there is a profound exploration of power between their relationship - perhaps not in the way you would expect. ‘Passing’ queries what is gained, and lost, through passing. Both women feel threatened by each other, experiencing shame in relation to their chosen identities, but in incredibly different ways.

There is significant rumination to be had off the page when reading ‘Passing’. While the entire novel is about racism, we very rarely see direct sentiments and language reflecting the attitudes towards Black people at the time. When this shockingly violent language full of hatred does appear, Larsen appropriately reminds us that this is not just a novel about the tense friendship (or lack thereof) between two women and their social engagements. It is the story of a society laced with racism and hate. Everything Irene and Clare do, or say, is interacting with this wider construct. Nothing exists in a vacuum. You are left wondering whether the novel is about passing to be seen, or hidden?

I got so much more out of this novella by reading it with others. I think, if I read it alone, I would not have had the experience I did. It encouraged much more depth of thought that is pretty hard to achieve on your own. I thought the first half was much stronger than the second, losing its tightness slightly in the middle, and on the basis of this I would call ‘Passing’ a borrow. A very swift read that suggests that identities can be just as performative as they are inherent. This interrogation from Larsen of the role of race within societal hierarchy will never lose its relevance.

‘Animalia’ by Jean-Baptiste Del Amo retraces the history of a modest peasant family in the fictional French village of Puy-Larroque, from 1890 to 1990, as they develop their small plot of land into a profitable pig farm. Five generations endure the cataclysm of war, economic disasters and the emergence of the industrialism of farming in an environment dominated by animals. Only the matriarch Éléonore, and her great-grandchild Jérôme, exist to be different from their family, offering a respite from the enduring barbarity. We witness five generations embrace, or struggle with, humanity's natural desire to conquer nature. ‘Animalia’ demonstrates that the violence of a family is eternal, passed from one generation to the next. Written in long, shifting prose that often verges on the disturbing, Del Amo offers no reprieve from the barbaric cruelty man inflicts upon animals.

‘Animalia’ embodies a narrative harsh and brutal, to the point of unease. Yet, it is one of the most fascinatingly compelling novels I have ever read. The family live within a consistently hostile environment; from living in poverty, to experiencing the significant agricultural limitations of the first World War and the suffocating job of running an industrial pig farm; there is no relief. The family is physically and emotionally bound to the land and the interdependence of man and animal. Misfortune and death characterise their lives as Del Amo seeks to comment on how our relationship with animals has evolved to become unrecognisable in the space of less than a century. He offers a stark criticism on food production, the inhumane industrialisation of farming and the cruelty that humanity is capable of.

The first half of the novel sees the intimate, but challenging, relationship the early generation had to their land and animals. Éléonore’s mother, unnamed and referred to as ‘genetrix’, is a harsh and unkind woman.1 She is cruel to Éléonore, but not to the animals. She has a more respectful relationship to the animals; there is no suffering, just killing. When Marcel, cousin of Éléonore, gets drafted in the first World War, Del Amo uses his experience as a catalyst for exploring how it changed his relationship with cruelty and violence. When Marcel returns, he struggles with his relationship to humanity. Instead of perceiving people as desirable, he views them as creators of cold-blooded hatred. Del Amo implies that Marcel’s experience of warfare is responsible for his aggressive approach to farming, resulting in the emergence and growth of the industrial pig farm.

Through the generations, and the environment they live in, Del Amo is articulating how violence is entangled within the structures of the natural and financial world, something inherent to both. However, there is sympathy to be had for the family in spite of all the terrible things they represent. Ultimately, they are having to respond to aspects of human existence that they cannot control, but have no choice but to keep going. There is a profound philosophical commentary about the relationship we have to creating, consuming and justifying violence as we exist on the planet. The farm seeks to represent the family's barbarism, and that of the whole world; a metaphor for the evil of humanity. The term, Animalia, is a classification which categorises all animals together, including humans. Through this title, Del Amo seeks to argue that no matter how many technological advancements human beings are privy to, we are still animals.

Comparatively, ‘Of Cattle and Men’ is a tame walk in the park compared to ‘Animalia’. I have never, ever, read anything like this novel. This book is not for the faint hearted. I am very good at reading confronting and gruesome novels (they are my favourite) but this was next level. At various points, my mouth was agape at the truly horrific and violent descriptions of life on the farm. Confronting doesn't feel enough of a word to convey the level of unease Del Amo brings to the page and forces you to sit with; I have never felt more uncomfortable. ‘Animalia’ is breath-taking in scope and intelligence. Just like ‘Childhood, Youth and Dependency’, I think this is going to be one of my favourites from the year.

I crave to be challenged by the novels I read, and ‘Animalia’ challenged me beyond my wildest dreams. I am truly enamoured with what a unique and phenomenal novel Del Amo has created. It was absorbing and I know I will be thinking about this novel forever. I would recommend this book if you have a strong stomach and call it a buy. It was like ‘East of Eden’ featuring the similar themes of isolation, fate and generational curses. But instead of Adam pathetically buying land and doing nothing with it, this family monopolises the natural world and creates a lineage of farmers and violence.

‘The Accusation’ by Bandi is a collection of seven short stories that paint a portrait of life in North Korea. Set during the period of Kim II-sung and Kim Jong-il’s leadership, they tell stories about the people living under this totalitarian regime. The characters come from a diverse range of backgrounds, telling the stories of parents, children and people on either end of the North Korea caste system. ‘The Accusation’ explores what happens during a political rally, a war hero’s disillusionment with the state, a man who is denied a travel permit to see his dying mother and those who realise they need to escape. Each story is full of humanity, devastatingly exploring the lives that are lived in such inhumane and abhorrent conditions in a country closed off to the rest of the world.

Before I actually review the book, I need to emphasise how truly remarkable it is that this book exists. ‘The Accusation’ was written by someone who risked their life to tell these stories and subsequently, many more lives were risked to smuggle it out. The fact that I can read this, that it has been translated and published, is an extraordinary privilege. Translation is political, and ‘The Accusation’ is the perfect example of the power and significance of translated literature. This novel is a historical first. No work denouncing the oppressive and antidemocratic regime of North Korea, by a writer still living in North Korea, has ever before been published. 2 Bandi is, unsurprisingly, a pseudonym, to protect his identity, family and life within North Korea. It is heartbreaking to know that Bandi has never held the book he created, only seeing a photo on a smuggled mobile phone to show him it has been internationally published. His bravery is something that none of us could comprehend and the value of this book in communicating the realities of life within North Korea is momentous.

I picked up this book to further my interest in learning about North Korea. Last year, I read ‘In Order to Live’ by Yeonmi Park which has garnered controversy. I have no interest in commenting on the accuracy of Park’s memoir, but Bandi’s work seemed like the best (book) step to take next. Although these stories are fictional, they do not always read that way. Every story is signed off with a date, ‘eg 12 December 1989’, implying that this is when the story was completed. Bandi unflinchingly presents life in North Korea as bleak and terrifying as he confronts the reader with the realities of life in this oppressive country;

‘We feel that to slide into oblivion would genuinely be better than continuing to live as we have been, persecuted and tormented. [...] We can only hope that our canoe on the vast blue will mark this land as a barren desert, a place where life withers and dies’ p.34 in ‘The Accusation’

‘Myeong-chol longed to let himself sob out loud, to stamp the ground or shake his fist at the sky. But, depending on circumstances, he knew that even crying could be constructed as an act of rebellion, for which, in this country, there was only one outcome - a swift and ruthless death’ p.98 in ‘The Accusation’

These are all stories about the accused, as the title suggests. Bandi presents the incomprehensible variety of ways that you can be accused of behaviour that is considered a rebellion against the state and the leader. The collection presents the contradicting nature of the regime and how inherently unjust living under this system is. I learnt so much from these stories - I had no idea that crying publicly could get you killed or that you needed permits to grant your travel to anywhere in the country, and these were frequently denied. All seven stories convey that a life lived in North Korea is one characterised by isolation and shame. Bandi makes the powerful argument that everyone living within North Korea is a highly skilled actor, constantly performing to the regime, having trained since the day they were born.

The majority of these stories are compelling in communicating the emotional and psychological impact that the residents of North Korea experience. Some stories meandered slightly, but they were always pulled back by the knowledge that they are rooted in real lives and experiences. This novel is arguably one that everyone should read, to hear a voice of the voiceless and to honour the courage of Bandi to write critically about North Korea while living there. Bandi has since published ‘The Red Years: Forbidden Poems from Inside North Korea’ which is supposedly even more crude than this collection - which fascinates me. Admiration for Bandi aside and putting my newsletter recommending hat on, I would call this collection a borrow.

And that concludes my September Reads! My favourite books this month were ‘Childhood, Youth, Dependency’ and ‘Animalia’. A friend and I were discussing recently the difference between loving a book because of the story, or because you are so impressed by the writing. I was so impressed by the writing in these books. Ditlevsen and Del Amo are remarkably talented, I am in awe of both of them.

My first read of October (like everyone else) is ‘Intermezzo’ by Sally Rooney. I would like to humbly consider myself one of the first fans of Rooney’s work. I often look at my first edition of Normal People, that I read in August 2018, and think how right I was to love her back then.3 Rooney’s writing has followed me from being a teenager into my mid-twenties. It is a pretty beautiful position to be in, to follow a writer throughout their life; their work defining periods of time in my own life. Despite having unreasonably high expectations, I am enjoying ‘Intermezzo’ - I am loving the dynamic between the brothers.

For October, I have a few atmospheric and unsettling reads lined up. I am not usually one to read ‘seasonally’, but I am giving it a go! Last October, I read ‘Ring Shout’ by P. Djèlí Clark and ‘The Possessed’ by Wiltold Gombrowicz - both of which I recommend as books to read this time of year!

I would also be remiss not to point you towards

’s newsletter this month if spooky is really your thing - she has it all covered.Let me know your thoughts:

❀ What have you read and enjoyed in September?

❃ Have you read any of these books? What did you think?

❁ Do you have any recommendations for me based off the themes for this month?

⚝ What is the last book you read where you were really impressed by the writing?

And a bonus question:

☞ Are you planning to read ‘seasonally’ this month? Do you have any unsettling and atmospheric recommendations for us all?

Thank you, as always, for reading. Let me know if you found a book you’d like to read.

See you next month,

Happy Reading! Love Martha

If you know someone is always looking for interesting and different books to read, share this newsletter with them!

Catch up on what you might have missed:

If you are interested in what I was reading in September 2023;

And before you go - if you enjoyed this, why not subscribe? <3

‘Genetrix’ translates to ‘mother’ or ‘foundress of the family’

This information & the line: ‘No work denouncing the oppressive and antidemocratic regime of North Korea, by a writer still living in North Korea, has ever before been published’ is pulled from p.229 in the ‘Afterword’ in ‘The Accusation’

I hope everyone can read the sarcasm here. However, I do think there is value in you knowing that my taste has always been right and ahead of its time xox

Such an interesting theme this month, especially with all of the animals! Have you written before about how you choose what you read each month? I'm curious if you pick things intentionally to align with each other thematically.

I've actually seen the 2021 film adaption of Passing, so I'm looking forward to checking out the novell as well. I've also put the Tove Ditlevsen memoir on my list. Did you ever read Kim Ji-young, Born 1982? (Did I read that book because you recommended it? LOL) The description of Childhood, Youth, Dependency gives off an energy of a much darker Kim Ji-young, Born 1982. Can't wait to dive into these! I've been spending some more time with the NYT Best Books of the 21st Century list of late (controversial, but I adore the curation), so my translated literature game has been dwindling.

Great round up, as always! I've read some mixed reviews about The Bee Sting so I wasn't sure whether I should make time for it or not, but your review has convinced me. I do love a good, complex family saga!

I've also had Animalia on my bookshelves for a while. I was intrigued by the synopsis and picked it up. This is the first time I've seen anyone review it and it has resparked my curiosity. I'm also very intrigued by the comparison you make to East of Eden – which I read and loved a few months ago. This has definitely bumped Animalia up the TBR!

My favourite read of the month of September was definitely The Book of Night Women by Marlon James. It's a very brutal read, but I highly recommend it if you can stomach it. It takes a little to get used to the Jamaican patois narration but once you're in it, you're in it.

Seasonal reading plans include reading books 2 and 3 in Jeff VanderMeer's Southern Reach trilogy in anticipation of the new book coming out at the end of October. And perhaps a Jonathan Strange & Mr Norell re-read!