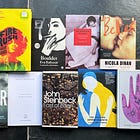

June Reads

Ancestors, generations and the passing of time & celebrating two years of 'Martha's Monthly'!

June felt like an eternity because at the beginning of the month, our beloved dog Bruce, who was almost 14 years old, died. When you have a pet who has been progressively greying for years, starts sleeping more and eating less, you do begin to prepare yourself for the inevitable fact that they will die. We knew it was coming, we actually thought it would happen a few years ago, and we knew it would be bad - but we never anticipated quite how bad. I have never known grief like it. Walking into every room in the house and expecting him to be there is a devastation that is impossible to put into words. The pain just shows how loved he was - Bruce came into the family when I was only 12, so he has been alongside me for over half my life.

Bruce was, and will forever be, the best dog. His company, charisma and love is something I will miss everyday for the rest of my life. I am crying while I write this, and I know readers who have pets, and have lost pets will be crying with me. What a gift it is to have known love like that. Before Bruce died, I had actually wanted to read ‘My Friend’ by Sigrid Nunez this month - but I think I might need to leave that novel untouched for a while. Even writing that title is breaking my heart because that is what pets are, friends.

At the beginning of July, we got a puppy, because the absence of a dog in the home was too much to bear. His name is Morris and he is equally delightful and exhausting. The shock of going from an elderly dog to a puppy is drastic to say the least, and the opportunity to read is becoming increasingly fleeting. I keep reminding myself this is just a phase - as everything in life is!

Bruce’s death, Morris’ arrival, and the books I read this month made me think about the passing of time - those who came before us, and those who will come after.

To see the translated reads from June on Martha’s Map, including authors from Chile, Puerto Rico, Spain and Italy, click here.

For those who are new, buy, borrow, bust is my recommendation key: Buy = I loved this book and highly recommend it. Borrow = I liked this book and think it is worth a read. Bust = I wouldn’t recommend this book from my reading experience.

‘Chilco’ by Daniela Catrileo

Chilco is the Mapudungun word for fuschia. It is also the name for Pascale’s home island. Pascale’s partner, Marina, grew up in the vertical slums of Capital City - a place scarred by centuries of colonialism and now irresponsible developers. Sinkholes are opening up in poor neighbourhoods, desperate refugees are arriving from the hinterlands. The indigenous and the poor are working for a machine that is destroying the earth from beneath their feet. Pascale and Marina flee the collapsing city to live in Chilco, they wonder if they can ever out run the crushing weight of centuries of colonial repression that have eroded indigenous culture?

Chilco is a novel that interrogates the wounds of colonialism and how they inflict themselves on individuals, communities and the land. Catrileo uses some of the central themes to our world today and takes them to the extreme, with climate disaster and refugee populations rising beyond comprehension.

Pascale and Marina’s world is on the brink of economic and environmental collapse because of humanity's uncontainable greed and an absent government. Capital City is characterised by people trying to protest against the powers that be, but ultimately failing in their demands for social justice. It feels as though Pascale and Marina are on a sinking ship the longer they stay in Capital City. However, when they leave for Chilco, the only island that has not been colonised, they arrive to find that it is not as freeing as they anticipated it would be. Pascale’s identity is never gendered by Catrileo. Instead, we witness how the community reacts to them with unease and contention. There is an unspoken political undercurrent of unease brewing on the island.

Chilco’s narrative is non-linear and predominately lacking in plot which often made it incredibly hard to follow. However, the thrust of the novel is the issues that are familiar to us; the climate crisis, threats to indigenous populations, and colonialism. Catrileo has taken the familiarity of some of the worst facets of our world and reimagined them in a different, but all too familiar context. The emotional thrust of the novel was never hard to discern, and the pain of having land stolen and communities threatened was remarkably strong. The grief of losing ancestral land was consistently centre stage throughout the novel, which is unsurprising given Catrileo is Mapuche. The anguish of the loss of language and memory is her community's lived experience. Chilco grapples with a displacement that is all too familiar for some, and completely unknown to others.

This strength aside, I wish there was a semblance of linearity in the trajectory of the novel. I frequently found my focus on the social issues, which are so central to the narrative, overshadowed by trying to discern what was going on. When a novel's central messaging relies so heavily on social justice issues that only continue to increase in severity, it is a disservice to the novel for the plot to be so obscure.

Chilco’s discussion of the consequences of the colonial and capitalistic exploitation of indigenous communities was evocative and scathing. It reminded me of the similar exploration within The National Telepathy - also published by Charco. It invites discussion about land; who can own it and take it. Catrileo articulates how indigenous communities are being treated and how colonialism does not end with the granting of independence to the colonies. The wounds of looting and pillaging live within the genetic code of families and communities for generations to come.

I read this with my friend

and I thoroughly enjoyed her reading of Chilco and how it made her look into her own country's colonial past (The Philippines). I liked the emotional exploration within this novel, and while impressed with what Catrileo is interrogating, I felt this novel fell short. While Chilco made me think extensively about the weight of the history of the world, the lack of clarity in the narrative was injurious to the power that this book could have held. I’d recommend it for the themes discussed nonetheless, but I would call this a borrow.‘Foster’ by Claire Keegan

I read my first Keegan, Small Things Like These last Autumn, and have been patiently waiting for the summer to read Foster - because I love nothing more than reading a book in the season it is set in. After waiting months, this novella was over in the blink of an eye, but I know the story will remain with me forever.

Foster is a novella about home, about how it isn’t a place but a feeling, and how love is expressed in action, in safety and routine. In a hot summer in rural Ireland, a child is taken by her father to live with relatives on a farm. When he drops her off at the Kinsella’s house, her father makes no indication when she will be brought home again. The girl is described as being ‘delivered’ like she is a parcel, and her father encourages them to put her to work because ‘she’ll ate ye out of house and home’.

There is no love in the way he talks about her, no love felt in the way he says goodbye; ‘Good luck to ye [...] I hope this girl will give no trouble’. The tragedy of her parents giving her away for the summer is most soberingly articulated by Mrs Kinsella herself as she whispers while the child sleeps ‘God help you child. [...] If you were mine, I’d never leave you in a house with strangers’. This is where the Foster reveals itself, not as a story of staying with relatives for the summer, but of an absence of love.

In the Kinsella’s home, she finds a warmth she does not recognise, an affection she does not know;

‘But this is a different type of house. Here there is room and time to think. There may even be money to spare’ 1

Mrs Kinsella’s household is well-tended and fully stocked. She picks tomatoes from her vegetable garden for breakfast, lathers her hands with shampoo to wash her hair. There is care in every action of Mrs Kinsella’s, something that the child can’t even describe;

‘Her hands are like my mother’s hands, but there is something else in them too, something else I have never felt before and have no name for. I feel at such a loss for words but this is a new place, and new words are needed’ 2

Keegan most powerfully paints a picture in what is not said. We don’t know what life is like at home for the girl, but we do see how carefully she watches Mrs Kinsella, in awe of her behaviour. All we do know is how nonchalantly they gave her away and how overwhelmed she is by physical acts of love. She is confused about being fed such a substantial breakfast, speechless at how Mrs Kinsella washes her hair. You feel the love that Mrs Kinsella gives the girl, and the lack thereof she is used to.

But there is something unspoken in the Kinsella household; the wallpaper in the room is covered in trains, there are clothes in the wardrobe for a boy. The Kinsella’s kind nature cannot overcome the rumours about their past and the gossiping that takes place. While something unspoken lives within the walls of the house, nothing is more daunting to the girl than the fact summer will eventually end.

It is a wonderful thing to be moved to tears by a story held in only eighty-four pages. Keegan is the most beautiful writer, crafting richly vivid worlds in such few pages. While, if I had to pick, I would choose Small Things Like These as my favourite, Foster contains an emotional heart that is just as touching. Keegan’s prose are sparse, creating a story that is to be felt rather than described. When I turned to the last page, one humid rainy afternoon, I had tears streaming down my face. Foster meditates on what it means to feel loved and that concept of family - that blood is not thicker than water and that the most profound love can exist where you’d least expect it.

Foster is such a gorgeous read, I would wholeheartedly recommend it and call it a buy! It’s short and sweet, exploring such a deeply human emotion in an unconventional way. I am all ears for which Keegan I should read next?

‘Reinbou’ by Pedro Cabiya

I chose this book primarily to learn about the Dominican Civil War - and I partially did, but in an entirely different way than I expected. While I anticipated prose rooted in history, I was met with a fable that explored the power of good.

Ángel Maceta’s father, Puro, was involved in the 1965 uprising, a response to the United States' attempt to try and destroy the Dominican Republic’s democracy. American soldiers are portrayed to be involved in corrupt schemes involving gold bars. Puro, depicted to be a heroic revolutionary leader, is betrayed by a friend in a Judas-esque dynamic and is being hunted. On the run, Puro asks to hide in a house that turns out to be Inma’s - a girl he fancies. In the final moments of his life, they make love and Ángel is unknowingly conceived. Shortly after, Puro is murdered.

Ángel never knew his dad, and eleven years later he is determined to find out what happened to him. Speaking to friends, family and neighbours, Ángel follows his childlike curiosity to uncover the legend of his father and the history of his family. Ángel repeatedly finds himself on the golf-course by his house, following the rainbows the sprinklers make, to dig for treasure. What he finds are objects which he attaches significance and hands out in the community, unaware that they are relics of the past that will eventually lead him to his fathers story. The villains of the past and Puro’s murderers still linger in the community, and the thrust of Reinbou exists within the tension of how, and when, will the past come up to meet Ángel.

Transparently, Reinbou is the type of thriller-fable where nothing in the plot makes sense until right at the end. Cabiya opens the novel with several narrative threads that appear disparate, only for him to slowly draw them together to create a novel that is captivatingly disorientating. Trying to deduce how the violence on the page represented the conflict and atmosphere at the time was intriguing. However, despite Reinbou being so rooted in a specific conflict, the novel lacked a distinct sense of place. In its exploration of violence and subjugation that characterises the history of so many countries, it could have been set anywhere. I appreciate the strength in this, articulating how universal the systems of power were in colonialism. Yet, because I approached it anticipating such a strong sense of place, I couldn’t help but negatively notice its absence.

Reinbou was occasionally too saccharine for my liking. Despite this, it never strayed too far from its anger in injustice. Cabiya grounds the narrative in morality, shaping Reinbou to manoeuvre from being a military thriller (of sorts) to a magical fable about the goodness within humanity. This is an unusual shift to be found in a novel that is primarily constructed around a civil war, but perhaps necessarily uplifting. Puro’s good nature is found within Ángel, emphasising both the inevitability of our interconnectedness with our ancestors, yet also hope of what a new generation and perspective can bring.

I felt misled by the blurb of Reinbou, it was not the novel I expected it to be, but I still enjoyed it. I was pleasantly surprised by its tone and how Cabiya managed to turn a story of war and violence into one of hope. There is a note throughout this novel that there is an inevitability for conflict in humanity, but an inevitability of justice and hope too. Perhaps during the current global political climate when it feels as though hope is hard to find, novels like Reinbou offer a respite that it is necessary to believe it will inevitably get better; potentially not in our generation, but the next. I would recommend this to anyone who enjoys fables and tales that end with everything falling into place - it reminded me of Augustown. I would call this a borrow!

‘I Gave You Eyes And You Looked Toward Darkness’ by Irene Solà

In a remote part of Catalonia sits an old farmhouse called Mas Clavell. Outside is surrounded by mountains visited by hunters, bandits and demons. Inside, an old woman lies on her deathbed while family and caretakers drift in and out. What the old woman doesn’t know is that all the women who have ever lived, and died, in that house are waiting for her to join them - they are preparing to throw her a party. As the day breaks, four-hundred-years worth of memories reverberate in the house, telling the women's stories. Stories of those born without tongues or tiny hearts. It all starts with Joan, the matriarch, who made a deal with the devil, uninterested in what the consequences might be. Generations of women pay the price for Joan’s self-serving wish to be married.

The concept of this book is unbelievably brilliant. The prospect of waking up in the afterlife surrounded by generations of women from your family is both horrific and hilarious. I Gave You Eyes opens with Margardia waking up to an eternity with those she believed she would escape, that she believes she is better than. Solà’s prose are vivid and comedic, her characterisation of the women is remarkable;

‘Margarida had awaited death with exhilaration. Her own, that is. She’d imagined it would be a luminous flare, a spasm of glory, a conclusive joy [...] accompanied by an army of angels playing lutes and trumpets. [...] Alas, [...] what a disappointment. Because when Margarida died [...] her snowy eyes fixed on everlasting joy, every bit of her was prepared [...] but there was no luminous flare, no spasm of glory, no conclusive joy, no smothering ecstasy. Just a circle of dirty, surly women. Grotesque and ordinary. That’s right. As sad as it sounds.’ 3

The women are depicted as both deeply human and other worldly. There is an animalistic element to their characterisation, primal in their experiences of life and death. These women have suffered, they have lived harsh lives and as the generations have passed, they have watched their daughters do the same. I Gave You Eyes is otherworldly in its exploration of religious figures, ghosts and demons yet deeply human in its discussion of womanhood.

Congregated in this house against their will, a camaraderie emerges between them as they ‘burst into laughter, shouts, shrieks, and applause so raucous’ at fart jokes together. They pass vicious judgement on each other and the lives that are unfolding in front of them, but encircle the bed holding hands ready to receive dying Bernadeta into the eternal fold. Solà’s prose is so fluid that it would occasionally put me into a trance, only to realise I hadn’t been paying attention to what was happening. The prose became nebulous and, while it effectively communicated we were amid a memory, it equally felt as though the grip of the narrative was slipping away. However, the comedic genius of Solà’s writing never strayed too far. The sense of feeling like I had lost my grasp on the story was always alleviated with Solà’s descriptions of the modern day, where the ladies' observations of ‘elves’ (people on screens) and horseless carriages (cars) consistently made me laugh.

There is a profound exploration within this novel about the natural world and our relationship to it. It ponders what it means to be connected with one another and part of the animal kingdom. I Gave You Eyes reads like a counteraction to our individualistic society, excavating stories rooted in the perversity of humanity and the theatrics of the natural world. It reminded me of both The Empusium and Cautery in its heartfelt exploration of the tenacity of women and ode to female companionship.

Although I didn’t always feel connected to the prose, I Gave You Eyes is unlike anything I have ever read and I remain deeply impressed by Solà’s craft. Her lyricism is spectacular at every turn. Her exploration of the various shades of womanhood were exquisite, articulating how friendship and unease characterise the lives of all women since the beginning time. The novel articulates our interconnected nature and the universality of womanhood. In the same way that Reinbou spoke to our humanity being bigger than what we conceive it to be, I Gave You Eyes speaks to the timelessness of our experiences - they are, unfortunately for our egos, not unique. Our emotions and thoughts have all been felt before by those who came before us, and will be felt by those who come after. Solà captures the sarcasm and beauty of our existence unlike anything I have ever read before.

I adored the strangeness of this novel and would recommend it to anyone who is looking for an obscure and comedic exploration of female and familial relationships. I would call it a borrow! There is a shared mythical tone in I Gave You Eyes with Solà’s first novel, When I Sing, Mountains Dance. But I Gave You Eyes is singular in its humour which is magnificent.

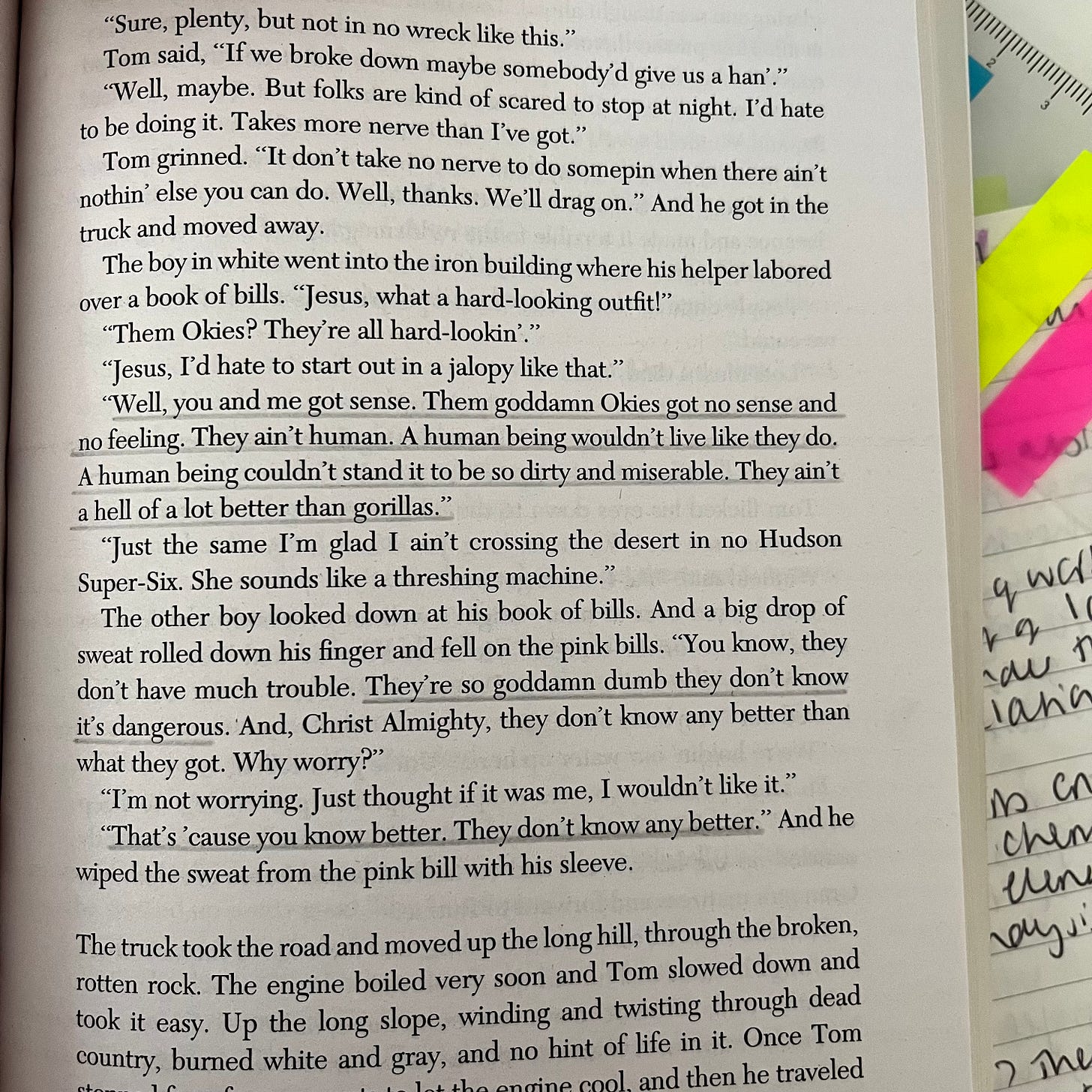

‘The Grapes of Wrath’ by John Steinbeck

Set between Oklahoma and California, The Grapes of Wrath tells the tale of the Joad family. The Joad’s are tenant farmers in Oklahoma and during the Great Depression of the 1930s, they are forced by the bank off their land. Generations of a family's work on the land is traded for a tractor as farming enters a new era of technological revolution. After seeing a flyer that said ‘fruit pickers needed in California’, and with nowhere else to turn, the Joad’s pack their entire life onto a truck and head west to the land of promise.

To bear witness to the Joads being forcibly relocated is painfully moving ‘How can we live without our lives? How will we know it's us without our past?’ and the reader is left grieving with them. The Joads grieve the loss of a member of the family; ‘the land is so much more than its analysis’. The deeply human story of the Joads is interspersed with philosophical chapters about what it means to be displaced and the effect the 1930s migration had on wider society. These chapters, which interrogate humanity and the systems we live under, are sublime. At the end of every chapter, Steinbeck details that the unimaginable suffering of the Joads is not unique as they interact with some of the worst of humanity, poetically interrogating how we live. He reflects on how the systems we live under irrevocably alter our humanity and take us away from who we are and who we are meant to be.

In an early review of The Grapes of Wrath, Edwin Lanham criticisms these commentary chapters on migration;

‘It is only in his commentary on the migration, the chapters interleaving the story of the Joads, that he is apt to be a little too hortatory. Here, in a grave, stately prose that seems to be half Jacobean and half Hemingway, he occasionally obscures the story with the moral-which is better borne out in the lives of his characters’ - Lanham, 1939, NYT

Migration is as old as humanity, but it has perhaps never dominated public discourse so viciously as it does today. The movement of people is timeless, but almost a hundred years on from when Steinbeck wrote The Grapes of Wrath, his ‘moral-which’ is hardly ‘too hortatory’ - it is ahead of its time. Steinbeck observed society was changing, articulating that this change might lead to the disintegration of our humanity. While a hundred years stand between Lanham’s reading and mine, Steinbeck’s call for compassion for the displaced is timeless. Perhaps Lanham, an early twentieth-century reader, could not understand the relevance of contextualising the Joad’s story within a wider shift in society, but a twenty-first-century reader can. Painfully, the call for compassion for those who have been displaced has never fallen out of relevance, which is sobering. Herein lies the value of reading old books, to understand how little society has changed. When reading classics that comment on society, readers gain insight into the cyclical nature of all of our lives and the issues that most passionately capture the public's attention.

While reading The Grapes of Wrath, all I could think about was how little we change. There persists a narrative that what we are experiencing is unprecedented, but perhaps it is worthwhile to remember that humanity exists in cycles. When I came across the passage above, I was in awe of the language used to describe those less fortunate, because it is deeply familiar to the rhetoric today. The media coverage of migrants is often dehumanising, but public opinion can be much more vicious. Earlier this year, Channel 4 released a show ‘Go Back To Where You Came From’, where controversially opinionated members of the public were sent to experience refugee life ‘close up’. There are not enough characters, and it is not the time in this review, to annihilate how dehumanising this show is.4 Nevertheless, I include it to articulate the unwavering cruelty expressed by about those who are forced to flee. A social experiment commissioned into a TV show to help the British public ‘empathise’ with those who are less fortunate.5 Despite being a century apart, there is little difference in those who want to ‘other’ the less fortunate; that the belief that refugees and/or migrants are responsible for the disintegration of society has withstood centuries. How unsettling to know that a lack of compassion for those who are less fortunate is so enduring.

The characterisation of the Joad’s was magnificent and the prose magical. Steinbeck writes stories full of heart and humanity, interrogating how we interact with each other. The dynamics between the Joad’s create a perfect picture of a variety of lived experiences in displacement. Rose of Sharon’s pregnancy offers both hope and despair in how they will manage, while other members are lost to the insurmountable hardship. Then there is the sheer tenacity of Ma and Tom Joad Senior, desperately trying to make ends meet and hold the family together. Ma’s emotional exhaustion from being the matriarch and provider exists in such harmony with the search for hope she refuses to give up on.

Despite all the bleak parallels about the state of humanity, Steinbeck offers hope - as all great authors do. Steinbeck suggests that the best of humanity can be found in the worst of times, with those the Joads meet on the road greeting them with compassion and offering help. While othered by those who are not in a similar position, they are embraced by those who are. Thus, hope lies in Steinbeck’s articulation of our ability to connect with one another. The Grapes of Wrath expresses, almost a hundred years, later that hope can be found in the darkest of places. It is just unfortunate we sometimes have to reach such places to find it.

Last June I read my first Steinbeck, East of Eden, and I loved it more than I could have ever anticipated. I very intentionally waited exactly a year to read my next Steinbeck because I loved East of Eden so much. But I think I loved The Grapes of Wrath even more. This novel is magnificent and I know it is going to be one of my favourite reads of the year. Everyone should read this - it is unbelievable. I unequivocally recommend it and call it a buy! My next Steinbeck on the shelf is The Pearl. I am officially in the Steinbeck hive - who knew this guy was such a brilliant writer?!?!?!

(My friend, Michael, wrote a piece last year about Palestine, The Grapes of Wrath and humanity on the move in the search of hope. It is brilliant and I recommend his reflections wholeheartedly)

‘The Dry Heart’ by Natalia Ginzburg

‘Tell me the truth’ I said

‘What truth?’ he echoed. He was making a rapid sketch in his notebook and now he showed me what it was: a long, long train with a big cloud of black smoke swirling over it and himself leaning out of a window to wave with a handkerchief.

I shot him between the eyes’ 6

These are the opening lines to The Dry Heart which is perhaps the best way to begin this review, to show this book is about an accumulation of rage.

Four years before she shoots her husband, a lonely young woman who lives in a boarding house meets an older man, Alberto. They appear as though they are lovers, but they are not. Alberto doesn’t tell her anything about his life, and yet, she convinces herself she will fall in love with him. Though Alberto doesn’t feel the same, she says yes when Alberto asks her to marry him, plagued by her own infatuation. So begins a relationship (if you could call it that) that is built on confusion and lies, and Ginzburg takes us back to the beginning. The Dry Heart examines how an unhappy marriage can end in murder.

I was enamoured with the starkness of this novella and its exploration of domesticity. Our protagonist falls in love with Alberto because she believes that is what she should do. She believes she is getting too old at 26, panicking that time is running out. Ginzburg interrogates the facade of domesticity and how it isn't the fulfilment patriarchal society suggests it is. She articulates that it is wrapped up in misogyny; all a woman has to offer and the fear of not offering it.

The protagonist has a friend, Francesca, who refuses to marry and is observant about resisting the gender roles society, and her parents, expect of her. She defies them and is always envied by the protagonist;

‘How easy life is, I thought, for women who are not afraid of a man’ 7

Alberto is a detached, emotionally stunted man who is having an affair with Giovanna in plain sight. Our protagonist is expected to accept it all; his allusivity, fluctuating disinterest in her and secrecy, even when they have a child together. Alberto is objectively a terrible man, but he never conceals the fact. The tragedy of this novella is within the protagonist choosing to be with him. She loses her mind all because of how she projected onto him, that he wasn’t who she thought he was.

While reading The Dry Heart, I kept thinking of the saying ‘we accept the love we think we deserve’ and how throughout this novel, Ginzburg is interrogating the tragedy of what women traditionally were made to believe. She chose Alberto because of what she is led to believe what womanhood is; marriage and children. She concedes to being subjected to mind-games because she truly believes that she should. Trapped between the rigidity of societal expectations on women and her own idealisation of love, perhaps there is inevitably that she shoots him.

Alberto is consistent in his indifference, giving nothing from the start. He has no societal expectation on his life. She cannot bear his inability to understand, his inability to care. Thus, with this dynamic between them, Ginzburg is analysing the marital dynamic between heterosexual relationships and their entirely gendered existence. Poignantly asking how much weight can wives, mothers, carry on their shoulders about conforming to society's ideals before it breaks them?

The Dry Heart is punchy and engrossing, I loved reading it! I would recommend it and call it a buy. This was my second Ginzburg, my first being All Our Yesterdays last summer. I have a copy of The City And The House on my shelf which will be my next! I am very gently working my way through her oeuvre. I love how she writes about women balancing the weight of society on their shoulders.

‘Blessings’ by Chukwuebuka Ibeh

Obiefuna is a vibrant child who loves to dance. He is performing well at his school, is sociable and loved in the community. When Obiefuna’s father, Anozie, witnesses an intimate moment of recognition between him and Aboy, the family's apprentice, he is banished to a Christian boarding school. Anozie sees an exchange of energy between Aboy and Obiefuna; ‘there was a stall in time, an instant when Obiefuna was convinced it was himself and Aboy alone in the world’ which puts the fear of God in Anozie as a traditional Nigerian man. Anozie sends him away without a second thought, precluding the involvement of Uzoamaka, his mother.

Obiefuna is sent to grow up in an environment that fosters hierarchies and shame. Meanwhile, at home, Uzoamaka is diagnosed with cancer. Uzoamaka grapples with her own shame about allowing Anozie to send him away. Mother and son stop talking and a chasm opens between them as they are swallowed up by fear which alters their relationship.

Blessings offers a social commentary on Nigeria in the early 2000s and how queer communities fought to survive while having a moving target on their backs. While I did wince that the thrust of the narrative relied so much on poor communication, the reasons for this softened such a tired trope. Obiefuna has grown up in a deeply conservative and religious society where being queer is deemed abhorrent. This is reflected by Anozie’s reaction to witnessing him gaze into a Aboy’s eyes and the attitudes Obiefuna encounters at school. From his peers, to religious leaders and those in positions of power, the shame of being queer is central to the running of the school; it is used as a fear to drive everything. Obiefuna senses this as soon as he arrives, and he is paranoid throughout about being seen for who he is;

‘He panicked for an instant, wondering if the boy had seen the look in his eyes, if this strange student had been able to see past the facade and read him somehow’ 8

Obiefuna’s boarding school is a microcosmic portrayal of Nigerian society. His character development is exceptional as we witness him transform from a confident, and enigmatic child to a withdrawn and slightly aggressive boy. His transformation was vivid, barely described but unwaveringly felt. Obiefuna becomes a shell of a person because of the way he has been treated, primarily by his parents and his peers. Thus, Blessings comments on the systemic nature of homophobia, how it bleeds into all corners of society and festers an environment that thrives off fear and violence.

Soberingly, the only person who knows Obiefuna for who he is is his mother. Yet, she fails him beyond articulation by never interfering when Anozie sends him away, never speaking up or pulling Obiefuna out of that school. Instead, she retreats, fearful of her cowardice. She runs away from her responsibility as a mother, and as a human being, to stop the abuse that she knows is happening in the boarding school. While the tragedy of a hateful society is monumental, the tragedy of Obiefuna’s mother passivity is even greater. Ibeh explores this tension between queer children and their parents in societies where queerness is so feared. Uzoamaka’s failure to interfere is painful to read as we witness Obiefuna learn that maternal love is conditional based upon your ability to conform.

Ibeh gives awareness that there is more at play here with Uzoamaka. Her fear at ‘defying’ her husband, speaking honestly about how she feels is reflective of the traditional gender roles that are so prolific in a religiously conservative society. She feels she is in no position to challenge her husband, despite knowing that how Obiefuna is being treated is wrong. Despite the strength at which Ibeh interrogates this mother-son relationship, I thought the storyline of her getting diagnosed with cancer was a distasteful cliché. Her sickness is used as a vehicle for emphasising the effect shame has on relationships. It is a tired common thread in coming-of-age stories to have a sick parent in order to communicate the themes of the novel, to emphasise that ‘life's too short’ for conflict.

While at boarding school, the tensions and emotional landscape of Obiefuna’s evolving identity were exceptional to read. But after Obiefuna leaves school, the ending of Blessings was rushed. Ibeh tries to cover too much timeline in the last quarter of this novel, chasing the deadline of the Nigerian government criminalising same-sex relationships in 2013, making them punishable by up to fourteen-years in prison. Although this ending offered exploration in the adult queer landscapes in Nigeria and some exceptional reflections about what it is like to be a queer child;

‘How much love is lost as gay kids grow up. We are robbed of the chance to experience the innocence of early teenage love. Because you spend all that time filled with fear, mastering your own pretence’ 9

It ultimately felt like an ending which didn’t quite fit the story. I appreciate why this ruling felt so necessary to include; emphasising that even after two decades of Obiefuna’s conflict with shame, his identity will always be shameful at home. Nevertheless, I was impressed with this novel and enjoyed reading it. I can’t believe it is a debut and I am eager to read whatever Ibeh publishes next. I would recommend it and call it a borrow!

And that concludes my June Reads! My favourite reads this month were The Grapes of Wrath and The Dry Heart.

My first read of July is ‘Friends and Lovers’ by Nolwenn Le Blevennec. I thought I would finish this before the end of June, but alas I did not! I am enjoying reading about friendship - something that is so rarely explored in the books I read.

‘Solenoid’ by Mircea Cǎrtǎrescu updated: I literally didn’t touch it this month. I sense I will not return to it until Autumn comes around because isn’t giving me summer reading vibes.

Happy 2nd Birthday Martha’s Monthly!!!!

One morning, two years ago, I started this newsletter. I came up with the name in 5 minutes (can you tell) and just went for it. I was so bored, lonely and desperate to talk to people about all the books I was reading. I wanted to have something in my life that was not about the fact I was very sick and struggling, instead about something I loved. Over the past two years my health has slowly improved, allowing me to do so much more than I could two years ago (I’m not bed bound anymore! What a joy!), but this newsletter has remained a constant anchor amid the turmoil of being chronically unwell.

I could never have imagined that ‘Martha’s Monthly’ would grow into what it has today, with almost 5,000 people sharing a love for books alongside me. Writing my monthly reads is my second favourite thing in the world. My favourite thing in the world is my comment section. I have met some of the most well-read, intelligent, kind and fascinating people in my comments that come back every month to talk to me about what they’re reading.

I said this last year and I will say it again today - please, never ever stop talking to me about what you’re reading. It brings me so much joy and I value what all of you have to say and recommend to me so much. Thank you for finding me in the black hole that is the internet and thank you for reading this newsletter every month. We’re all meant to be together! I love you! I am unbelievably grateful for every single one of you that reads this newsletter - thank you, from the bottom of my heart, for your companionship and your book recommendations.

Let me know your thoughts:

❀ What have you read and enjoyed in June?

❃ Have you read any of these books? Would you like to?

❁ Do you have any book recommendations for me based on the themes of this month?

☀︎ How is everyone finding their reading life this year? I feel like I am reading a lot slower in comparison to past years and I am having to try very hard to fight the feeling I am being ‘slow’. Reading ebbs and flows so much, but sometimes when it ebbs too much one way it can feel like some sort of regression. There were (are) SO many books I want to read this year and the fact we are half way through, and so many remain untouched, makes me feel agitated! I am trying my best to let it wash over me.

Thank you, always, for reading.

All my love and happy reading!

Martha

If you enjoyed this newsletter, why not share it with a friend or someone you’d like to impress with your impeccable taste <3

Catch up on what you might have missed:

What I was reading in June 2024:

And June 2023: (my first ever newsletter! cringe, but always worthwhile to remember how far I’ve come)

Remember to subscribe if you enjoyed this and want to receive recommendations straight to your inbox!

I endeavour to always introduce you to books that don’t get coverage elsewhere - that is a promise.

P.13 in ‘Foster’ by Keegan

P.18 ‘Foster’ by Keegan

P.5-6 in ‘I Gave You Eyes And You Looked Towards Darkness’ by Solà

Because how else do you get them to care or have empathy!!!!!!??!?

P.1 in ‘The Dry Heart’ by Ginzburg

P.95 in ‘The Dry Heart’ by Ginzburg

P.29 in ‘Blessings’ by Ibeh

P.211 in ‘Blessings’ by Ibeh

Martha, I’m so sorry about your loss and thank you for sharing Bruce’s story. Pets are such a special gift to us humans.

Good luck with the little guy! With our puppy (now 2) it was like having a toddler and also the work is never done 😅

Congratulations on Martha’s Monthly 2nd anniversary! I look forward to your reading report every month.

I also enjoy Clare Keegan’s writing. I read through all of her work last year. While I feel that Small Things Like These and Foster are my favorite (her best?) work I think she’s a very talented writer and will read anything she puts out. If you want to read more of her So Late in The Day (the short story as well as the short story collection) is a good progression. I personally enjoyed The Forester’s Daughter.

I have The Family Lexicon by Natalia Ginsburg on my summer tbr as well as East of Eden. I’m even more motivated to pick those up after reading your reviews of the two authors’ adjacent works.

I just finished Silk by Alessandro Barrico. It’s now sitting on my favorites of the year list. Have you read it?

Wishing you a great reading month!

Omg, I loved The Friend! I really want to watch the movie adaptation with Naomi Watts too. I read an interview about how the dog was such a good actor. I am so, so sorry to hear about Bruce, and also teared up reading your story. Dogs are such gentle creatures. They love in such an unselfish way, they are so loyal, and so forgiving.

Very interesting June reads! I wonder if you've ever considered editing other writers. I love Irish fiction (English majors are obsessed with James Joyce!). Claire Keegan's writing is a master class in the novella, and I have read every single novel of Sally Rooney. Intermezzo is really her best! (I really enjoyed your review of her book). I think that the Irish are the best minority writers in UK English, and then it's a tie between Indians and Sri Lankans (so underrated) afterwards. I have not read enough African minority writers in English though. And then you go into the layers with translation of African minority writers in French, translated into English, Algerian writer in French, translated into English, etc.

I find it interesting how minority Filipino writing in US English compares to those writers and what I might learn from them. I've read John Steinbeck's East of Eden, and a lot of Filipino writers were trained to learn and write in English by reading Steinbeck, Fitzgerald, and Faulkner - including my great, great grand uncle Nick Joaquin, but also Tagalog writers like Edgardo M. Reyes who wrote Sa Kuko Ng Mga Liwanag (In the Claws of Brightness), which if there is ever an English translation of the book, I recommend and think you'll enjoy.